[Disclosure: AgFunderNews’ parent company AgFunder is an investor in Integriculture]

Everyone agrees that the cost of cell culture media has got to come down dramatically if cultivated meat is going to gain any market traction. But what’s the most efficient way to do it?

Right now, industry stakeholders are exploring multiple avenues, with some seeking out plant-based alternatives to animal ingredients such as albumin, others dedicated to engineering microbes and plants to express pricey growth factors, and some tapping plasma from ‘healthy living’ cows to replace FBS (fetal bovine serum).

Tokyo-based startup IntegriCulture, however, takes a different approach, says CEO Dr. Yuki Hanyu, who cofounded the business in 2015 with Dr. Ikko Kawashima (CTO).

Instead of buying costly recombinant proteins or trying to replace all the key components in a complex product like FBS, IntegriCulture aims to mimic the process in the body where organs secrete growth factors which are circulated to other tissues via the bloodstream.

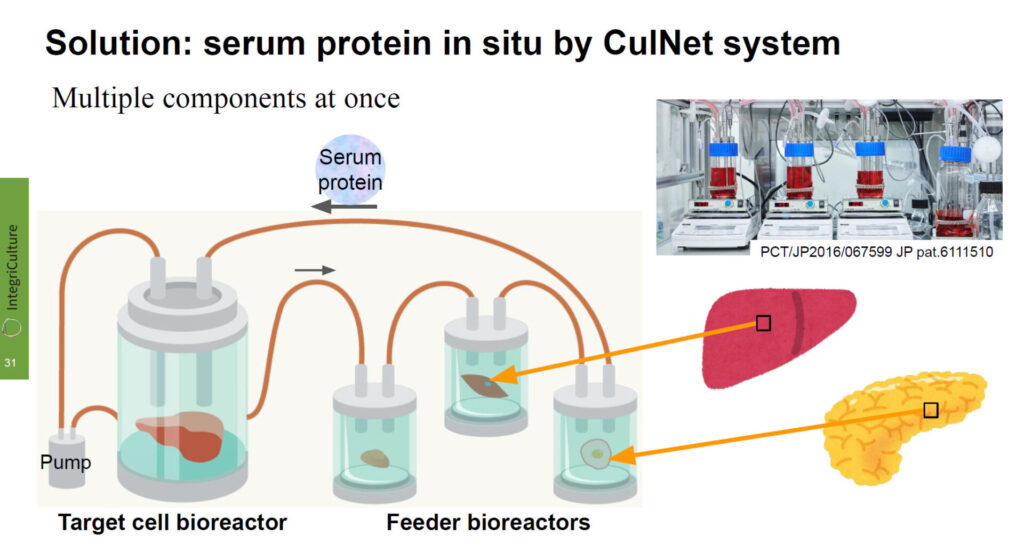

Enter IntegriCulture’s CulNet system, which deploys a central tank containing cells that will be used to make cultivated meat (muscle, fat, etc.) and a series of ‘feeder’ tanks that contain other cell types such as liver or placental cells.

The feeder cells secrete growth factors (proteins that stimulate cell growth and differentiation – typically the most expensive part of any growth media) that are then fed into the central tank.

Rather than producing everything in-house, IntegriCulture plans to offer B2B enterprise solutions whereby partners can produce their own cell-cultured meat utilizing IntegriCulture’s technology. It is also starting to generate revenues from the production of Cellament, a nutrient-rich serum targeting the cosmetics industry, Hanyu (YH) tells AgFunderNews (AFN).

“We are a cellular agriculture infrastructure company, not just a cell cultured meat company.”

AFN: Give us the 60-second origins story…

YH: I’ve always been a big science fiction fan and I was making videos and drawings of interplanetary spaceships and cell cultured meat long before I started working on it! When I started to really focus on cultured meat around 2014, I wasn’t thinking about founding a business, but more an open-source project.

So I founded [a nonprofit called] the Shojinmeat Project and also met my cofounder and CTO Dr. Ikko Kawashima. It was basically somewhere to start, because we didn’t have any money. Initially it was university students, some postdocs and even some high school students meeting at Lab Café in Tokyo, and it was very casual. It’s not even an incubation space, just a place where people hang out.

AFN: When did you come up with the idea of the CulNet system?

YH: From the beginning we wanted to find a way to make cell culture media at lower cost. I think many companies were starting with a very expensive process and trying to make cost reductions whereas we were trying to make a lower cost system work from the beginning and then make performance improvements. So Dr. Ikko said why not supply all the necessary serum components with a co-culture approach?

With this co-culture approach, which he tested in his laboratory, growing meat at home actually becomes a realistic option.

AFN: What cells are in the feeder tanks and what do they produce?

YH: We use placental cells, which are very effective at producing a full range of serum components, not just things like insulin-like growth factors, but also a kind of homolog for transferrin [a protein helping to promote cell viability, growth, and differentiation]. We also use liver cells, which are very good at producing components such as albumin.

The feeder cells proliferate up to the capacity of the bioreactors and just stay there and keep on secreting serum components.

AFN: How long do the ‘feeder’ cells remain productive?

YH: We’re improving this all the time, so about a year ago, they were productive [secreting the serum components IntegriCulture wants] for 30 days, but recent results show about 70 days and counting.

AFN: CulNet seems like an elegant system, but is it scalable?

YH: What we’re doing at IntegriCulture is basically mass producing cell culture serum, and entirely bypassing the expensive extraction and purification process [that is required if growth factors and other serum components are produced by, say, E.Coli bacteria in fermentation tanks].

We benchmark against other alternatives and it seems our approach is still much cheaper, because we’re not just producing growth factors. We’re making serum which contains multiple components: growth factors, albumin and transferrin, but also lipids and exosomes and things that [microbial] fermentation can’t make.

Feeder bioreactors can be much smaller than the main proliferation bioreactor, so scaling is less of an issue if you just want to produce serum.

AFN: What is your business model? Are you a cultured meat company, a cell culture media supplier, or a provider of enabling tech for the broader industry?

YH: We can provide different components like basal media or cell cultured serum or the CulNet system unit that produces the cell cultured serum although ultimately we are probably heading towards some form of CDMO [contract development and manufacturing organization] or CRDMO [contract research, development and manufacturing organization] model.

AFN: What progress have you made on partnerships with food companies interested in your tech?

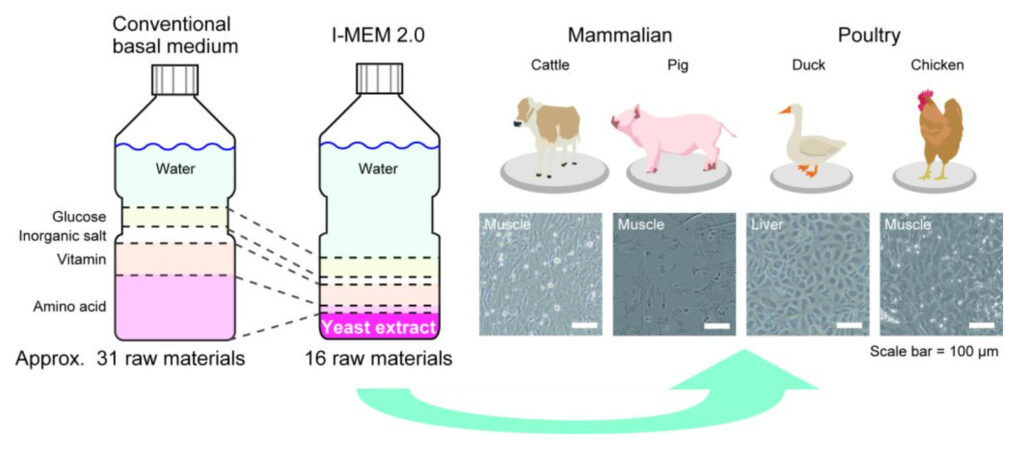

YH: In 2021, we formed the CulNet Consortium, where we brought together companies across the supply chain focused on different challenges, and now we have active R&D programs for pretty much all the topics from downstream processing to the basal media [the part providing essential nutrients such as glucose, amino acids, inorganic salts, vitamins, and buffers].

IntegriCulture offers a service called CulNet Pipeline, which aims to equip our clients with full-stack capability in cellular agriculture. For certain countries the system has benefits in establishing a complete cell-ag supply chain within a country, as certain IP-heavy components like recombinant protein may have to be imported.

The CulNet Pipeline service starts with feasibility, then the development of customized cell-cultured serum, possibly with the help of AI, and then scaling by fitting with scaled product bioreactors. The client gets preferential or exclusive usage rights for the cell-cultured serum. The R&D fee is compensated monthly.

We work with [Japanese food processing conglomerate] NipponHam and [Japanese aquaculture and food processing company] Maruha Nichiro as described above.

We can’t disclose the details, but we have been having conversations with [Japanese instant noodle maker] Nissin Foods dating back to the 2018 Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) Mirai Program on cellular agriculture.

AFN: Is IntegriCulture planning to launch its own cultivated meat products grown using the CulNet system?

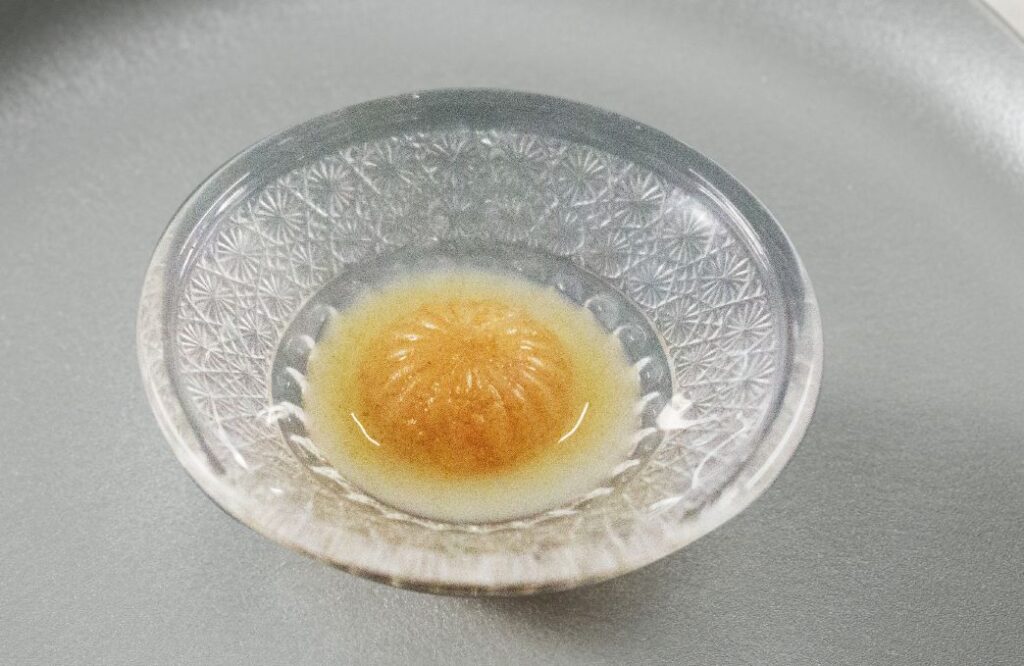

YH: So far, we’ve been growing duck liver cells to make foie gras with food-grade basal media only, replacing some of the refined amino acids components with yeast extract. We basically proliferate them and then change the media to trigger the liver cells to start accumulating fat. We’ve also worked on growing chicken muscle cells.

In the short term we have to prove ourselves, so we’ll be scaling up to produce foie gras for restaurants. But ultimately, we’re aiming to make universally accessible infrastructure that anyone can use, large scale or small scale, for the production of food, cosmetics, or things like leather.

Due to the limited amount of funding we’ve raised to date, less than $20 million, we are only up to about 100-liter scale for the combined feeder bioreactors, which can produce cell cultured serum for about 100 kilograms of meat per month.

We’ve also been experimenting with different bioreactor designs for the main proliferation bioreactor, but it’s a challenge, because for food, regulators basically want to see a pilot plant, which we have not been able to build due to [lack of] money, so it’s a chicken and egg situation.

AFN: How are investors viewing the cultivated meat space now?

YH: Initially, there was a hype bubble, and then people saw that the challenges to scaling up are much bigger than some people originally thought, although people who are knowledgeable about the technology knew this from the start.

So now there is more anxiety and fewer enthusiastic [venture] investors. However, strategic investors are still there, and at least in Japan, some of them are getting more serious about getting involved in cellular agriculture.

Recently the Japanese government also launched program for cellular agriculture, so the CulNet Consortium is trying to go for some of that [funding].

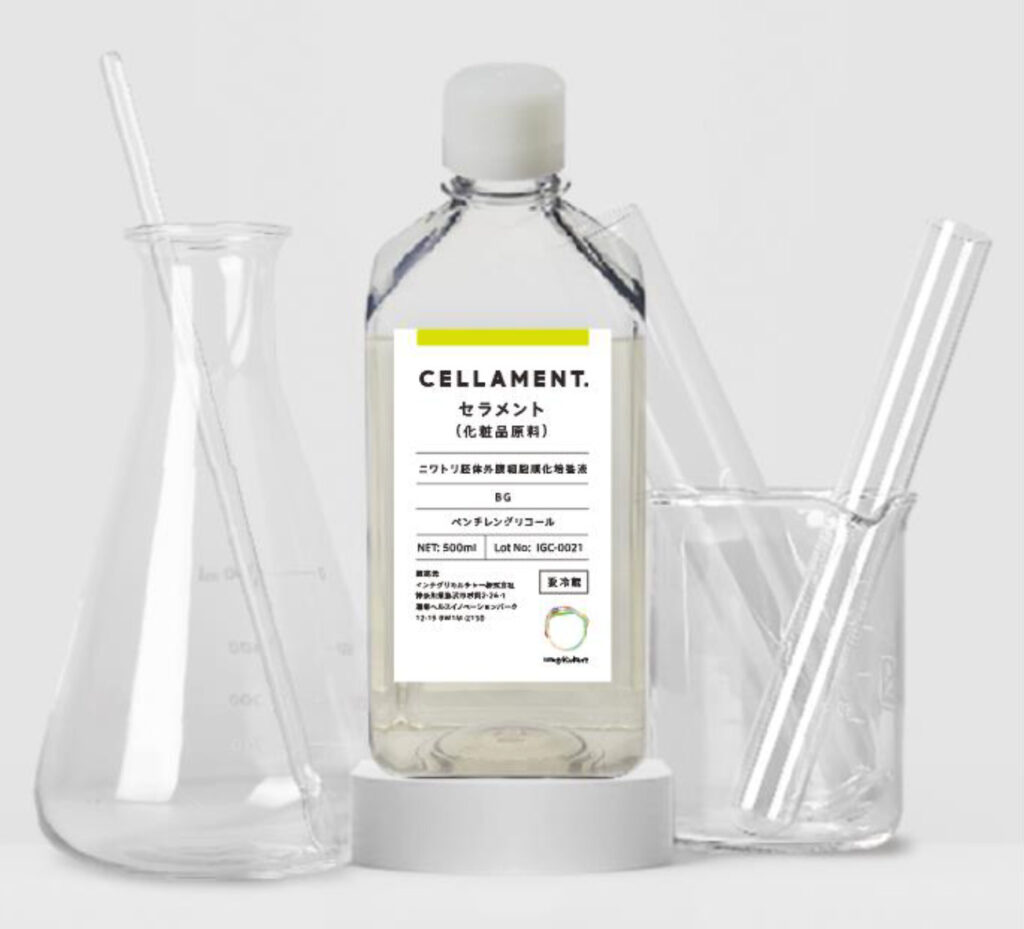

AFN: You’ve recently started selling a branded skincare ingredient called Cellament. What is it?

YH: We are a cellular agriculture infrastructure company, not just a cell cultured meat company. Through cosmetic products, we are trying to popularize the idea of cellular agriculture and Cellament is already selling quite well.

It’s a conditioned medium from stem cell culture but we use chicken placental equivalent cells instead of human stem cells. (Described on the ingredients list as: ‘Chicken egg extracorporeal membrane cell conditioning culture medium,’ Cellament is created by culturing amnion, yolk sac, and plasma membrane cells, the first things established in a chicken embryo following fertilization.)

AFN: How does Cellament benefit skin?

[Editor’s note: According to a press release issued by the company in 2021, Cellament is claimed to inhibit the activity of enzymes that degrade hyaluronic acid and elastin, which are key to skin elasticity; accelerate the production of fibroblast growth factor (a protein facilitating faster skin cell turnover, increasing smoothness; increase the production of enzymes and proteins associated with moisture retention; and mitigate UV damage. It does not reference any human clinical trials to support these claims.]

YH: Because it’s a chemically undefined mixture, it’s hard to pinpoint what is doing what, although we’ve identified certain compounds we think are responsible for its beneficial effects. By applying Cellament, it is like old cells get back to the gene expression patterns of younger ones.

AFN: What interest have you had in Cellament?

YH: We’ve had a lot of interest from Japanese companies. One is Euglena, which started as a microalgae company. Another one is Oppen Cosmetics, which is an online cosmetics brand, and there are a number of others. The feedback has been really good. With Euglena, the first lot sold out very quickly and Oppen is now looking at putting Cellamant into a wider selection of products.

AFN: What keeps you awake at night as a founder?

YH: Day-to-day organizational challenges, fundraising—where I think we need to articulate our technological progress into more effective investor decks— and corporate engagement. Lots of companies are interested in cellular agriculture; they ask a lot of questions and we spend a lot of time with them, but they don’t always make a decision.