Growth factors—signaling proteins used to stimulate cell growth and differentiation in cultivated meat production—come with a hefty price tag, putting pressure on firms to express them more efficiently in everything from fruit flies to microbes. But is it more cost effective to produce them in plants?

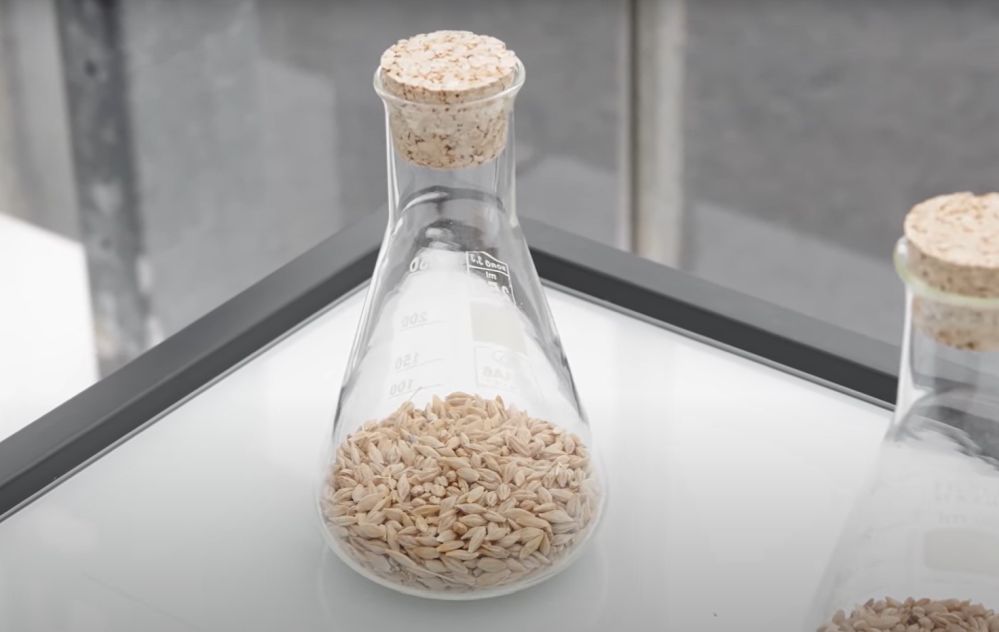

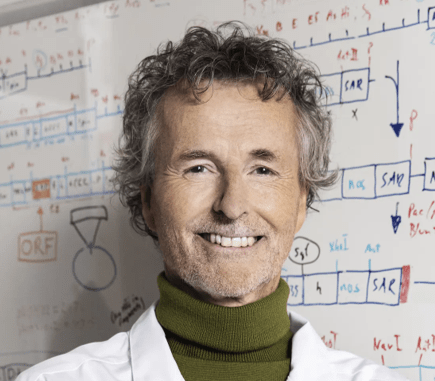

Founded in Kópavogur, Iceland, in 2001 by Dr. Björn Örvar (CSO), Dr. Einar Mäntylä, and Dr. Júlíus Kristinsson, molecular farming pioneer ORF Genetics uses barley grain as a vehicle for recombinant protein production.

The company initially focused on human growth factors and cytokines for stem cell research and regenerative medicine. It then moved into cosmetics, producing EGF, a protein that stimulates the production of elastin and collagen and now plays a starring role in its high-end skincare line BIOEFFECT.

Animal growth factors used in cell culture media for cultivated meat were an obvious next step, says Dr. Örvar (BO), who caught up with AgFunderNews (AFN) to discuss why producing such high-value proteins in barley, rather than E.coli, could “dramatically” change the economics of cell cultured meat production.

AFN: What’s so attractive about barley as an expression system for recombinant proteins?

BO: Initially, the idea was to develop a production platform for specialty proteins that could bypass yeast or E.coli, which require expensive precision fermentation facilities. The idea was to use plants and to produce these proteins in the seeds.

There were parties developing recombinant proteins in corn, but we were always interested in barley as a host species as it could be both ecologically and biologically contained. By ecologically contained I mean it would not invade natural habitats from the agricultural sites. By biologically contained, I mean that it will be self-pollinating, not cross-pollinated by insects or wind.

Since then, the Agricultural University of Iceland has conducted some field trials here in Iceland for few years showing exactly this containment.

We also wanted to use a plant that could be grown more or less everywhere, in remote areas, in soil that was not the best, in not the best climate, so we would not have to select prime agricultural land.

AFN: How are you inducing the barley plants to express animal proteins?

BO: There are two kinds of production systems you could use. One is transient expression where you would have to introduce DNA [the foreign gene encoding the desired protein] into the plant using bacteria, usually for production of [the target proteins] in leaves. This can be very fast, but batch-to-batch control is more difficult and probably the cost is higher.

What we do is produce transgenic plants [whereby the foreign gene is integrated into the plant’s DNA so the plant passes the gene to its progeny during reproduction, enabling a consistent line down the generations].

We just propagate this barley and we have a working seed bank. You sow the seeds and you get more seeds [that contain growth factors]; you don’t have to keep adding the DNA [as you would with a transient expression system].

AFN: Tell me about your growing system…

BO: We can get at least three generations a year in our greenhouse, where we use hydroponics and have access to cheap, sustainable geothermal energy for heat, light and power. But for production on a larger scale we’ve been doing in-field cultivation in Canada for the last nine years.

AFN: How do downstream processing costs for extracting growth factors in barley compare with those for microbial hosts such as E.Coli?

BO: You can split the cost of producing recombinant proteins into two phases. The first is to produce the protein itself in a host cell, the factory basically. And our ‘factory’ is simply the seed, so we have a very low cost of production versus setting up precision fermentation facilities for microbes such as yeast or bacteria or CHO cells [Chinese hamster ovary cells commonly used in the production of recombinant proteins and in scientific research].

The second phase is the downstream processing, where costs can be similar in both systems if you need a very highly purified protein for something like stem cell research as with our ISOkine growth factors.

However, for growth factors used in cultivated meat production, we don’t have to have such highly purified proteins. [At lower levels of purity] the growth factors will still be fully functional. So for example, our MESOkine growth factors for cultivated meat are a combination of growth factors and barley proteins and they work at least as well as highly purified ones.

So, you can just imagine how much that reduces downstream processing costs vs microbial platforms where end customers do not want endotoxins getting into their products, so need higher purity [endotoxins are lipopolysaccharides found in gram-negative bacteria such as E.coli that can be released from the bacterial cell wall during protein production ].

Another benefit with barley is that we do not have to do any post-production modification of the protein, whereas sometimes with E.coli you have to refold the protein because the treatment was so harsh. Barley cells can actually produce the protein more or less correctly formatted and fully functional, just like animal cells will do.

AFN: Is it risky making growth factors for cultivated meat given that no one really knows if this market will take off?

BO: When we started, we didn’t have the luxury [of being able to operate for years without making a profit], so we started with the stem cell research market where we still have loyal customers and then we got into cosmetics.

We developed our own skincare line, which became extremely popular and is now sold in over 30 markets including mainland China, and the company became quite profitable such that we could work on [potentially higher-risk] projects such as animal growth factors for cultivated meat.

AFN: What animal growth factors can you make and what reception have you had?

BO: I’d say we started looking at this market seriously in early 2019 and asked could we bring down the cost of animal growth factors dramatically? At first we got a small grant from the Icelandic National Technology Fund, and later we got a €2.5 million ($2.7 million) grant from the EU to develop a portfolio of animal growth factors for cultivated meat.

Today we have a portfolio of porcine, bovine and avian growth factors probably covering at least 80% of the growth factors that are in demand by cultivated meat companies and at about 90% of the volume they need.

Since we launched our MESOkine line in Q4 of 2020, we’ve been quite successful in reaching out to cultivated meat companies around the world. Many have tried our growth factors and are starting to purchase them, and we have been part of several food safety dossiers [required for regulatory submissions].

I would say probably 10-12 growth factors in total are more or less what this industry needs.

AFN: How are regulators looking at growth factors used in cultivated meat?

BO: We still do not have a complete picture of how regulatory authorities will handle them. But mostly I think they see them as processing aids as they are not present or are only present at trace levels in the final product. We don’t know yet if they are going to look specifically at the host system or not.

AFN: How bullish are you about cultivated meat?

BO: We have a strong belief in this industry and we have a very high capacity [for recombinant protein production] compared to most other companies. However, we don’t know exactly when it will take off at scale and I’m still not sure we have seen the best technology yet.

We also need to see a stronger supply chain for cell culture media if we’re talking about mass production, as we’re only focusing on one part of that chain [growth factors]. There are other parts of the media that also need to be improved and scaled up for this to work, and the source for those ingredients ultimately has to be plants.