On paper, insect farming ticks all the right boxes. Black soldier fly larvae (BSFL), mealworms and crickets can transform food and agricultural waste into high-quality protein, oil and fertilizer at record speed with a fraction of the inputs required by other protein sources.

But its green bona fides notwithstanding, industrial-scale insect ag is not for the faint-hearted. And if we’ve learned anything over the past decade, it’s that if you move too fast, you’ll break things—a mantra that may play well in tech, where startups learn from their mistakes and rapidly move on—but is less suited to agriculture, where lengthy iteration cycles, high CapEx, and a limited pool of investors mean financiers that have got their fingers burned can be reluctant to put their hands back in their pockets.

“A lot of people say you’re just sprinkling some maggots on food waste, how hard can it be?” says Miha Pipan, cofounder and CSO at UK-based BSFL farmer Better Origin. “But if you want to do it consistently at scale, it’s an intricate combination of biology and engineering. If you jump too quickly into the deep end of the pool, you’ll get into difficulties.”

Funding insect farming: ‘Investors have seen a lot of capital not achieving very much’

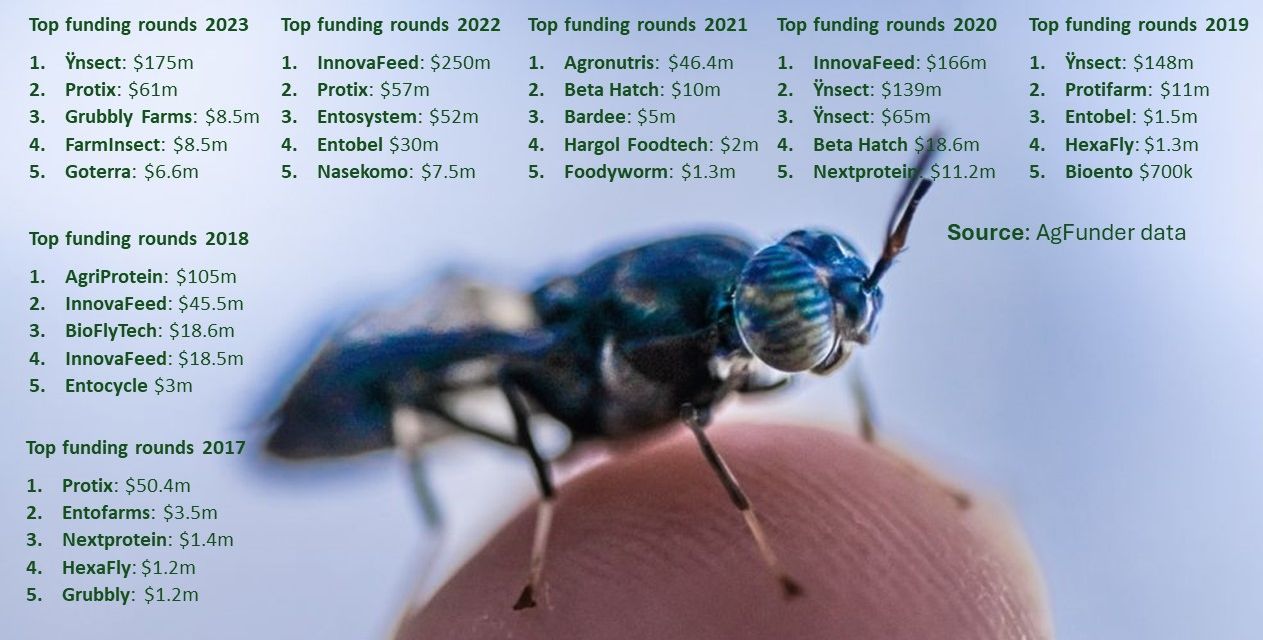

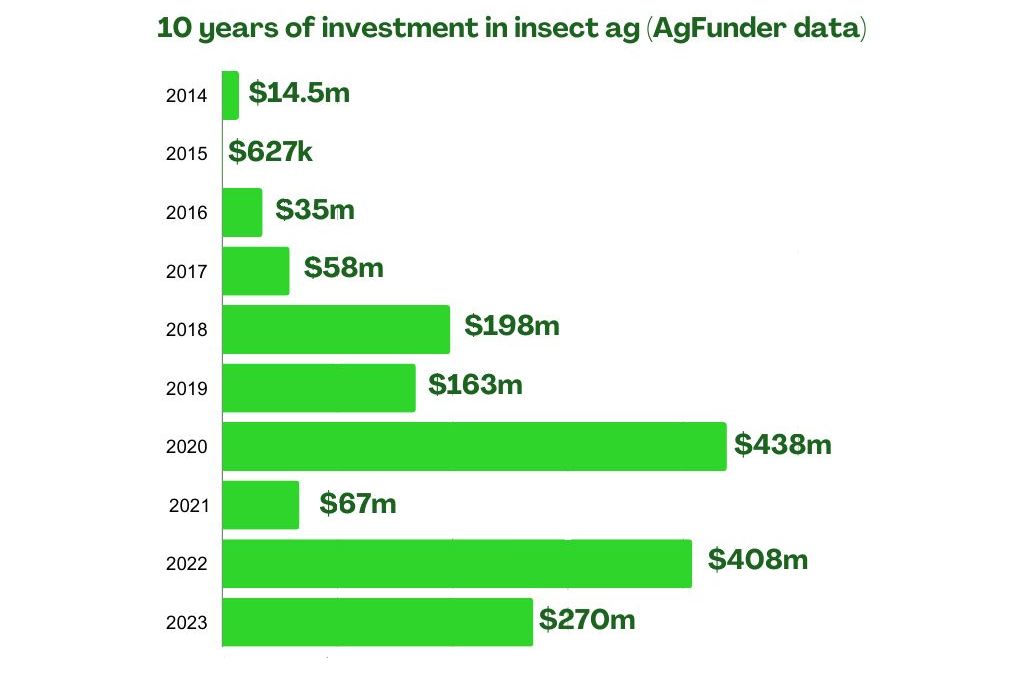

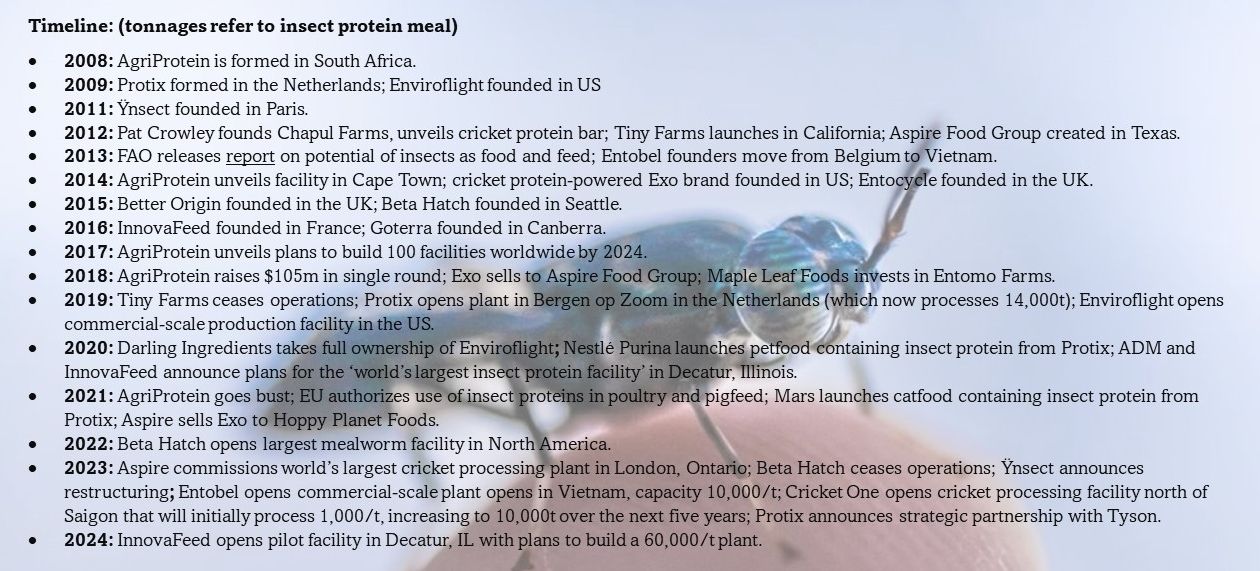

Investors— who have pumped $1.65 billion into insect farming over the past decade, a tiny percentage of the $205 billion pumped into agrifoodtech startups over the same period according to AgFunder data—have “seen a lot of capital not achieving very much in this space,” says Sandy Singh Sandhu, CFO at Singapore-based Entobel, which recently opened a BSFL facility in Vietnam capable of producing 10,000 tons of protein meal a year.

“Milestones have been missed and there hasn’t been enough de-risking of the technology.”

And now that the heady days of cheap money and crazy valuations are firmly in the rearview mirror, the chances of getting VC funds to finance huge CapEx projects have shrunk considerably, adds Mohammed Ashour at Aspire Food Group, which is commissioning a 12,000/ton/year cricket processing facility in London Ontario.

“The cost of capital has shot through the roof, so if you want to build a $150 million to $200 million plant, it’s a very expensive way to finance it through equity. About 25% of the funding for our plant in Ontario came from government grants, about 30% came from a loan, and then the balance came from equity.”

He adds: “My expectation is that once this facility starts to generate the unit economics that we’re targeting, we’ll be able to access debt financing and other forms of capital with much greater ease. Some of our customers with pretty healthy balance sheets may also front some portion of the capital costs and we could enter into a joint venture type of model where we’re not having to carry the burden of the full capital deployment for it.”

“For all of these new food production facilities, whether it’s vertical insect farming or precision fermentation of cultivated meat, there has to be ways [to finance them] outside of VC and private equity because the cost of capital has gotten too high.” Mohammed Ashour, CEO, Aspire Foods Group

Startups were being ‘pushed to do things too quickly’

At Dutch insect farmer Protix, which is working with Tyson to build a large-scale facility in the US, cofounder and CEO Kees Aarts says insect farming startups have been “pushed to do things too quickly.”

“You can’t come in with a Silicon Valley playbook and outcompete [a legacy industry] in three years with growth on an exponential curve,” says Aarts, who first got into bugs back in 2009, when there was no playbook and no regulatory framework for large-scale insect farming and pioneers in the space were effectively building the plane while flying it.

“This is not a software business,” says Aarts at Protix, which has raised around €227 million ($246 million) in debt and equity to date and now operates a large-scale BSFL facility in Bergen op Zoom in the south of the Netherlands processing 14,000t/year. “It’s about building assets that need to continuously perform for 10-20 years, where quality and constant improvement cycles are more important than quick fixes.”

With any new industry, meanwhile, “there’s a big toll on the pioneers,” says Pipan at Better Origin. “AgriProtein [a UK/South Africa based business which secured the largest series A round for an insect ag company in 2018 with an $105 million investment from an undisclosed investor but went bust in 2021] is an interesting example because they expanded all around the world and were trying to doing multiple things at once, which was too much too quickly.

“I suspect that coming from a more permissive legislative framework in South Africa into more regulated markets was also a challenge.”

John Diener, who worked at AgriProtein before starting high-tech shrimp farming operation Vertical Oceans, adds: “There was a mismatch between where they thought they were in terms of readiness to scale versus the reality.”

Commercial due diligence? A lot. Operational due diligence? Less so…

While investors have told insect farmers they must have offtake agreements from customers before they will fund large facilities, they haven’t always been as assiduous in assessing those startups’ ability to scale their operations, claims Dr. Virginia Emery, an entomologist and founder at Beta Hatch, which opened North America’s largest mealworm farm in Washington in summer 2022 and shut up shop in the fall of 2023 after running out of money.

“From what I’ve seen, due diligence has focused very heavily on the commercial side as opposed to the operational side. Many people also see insects as a commodity replacement for fishmeal when there are much higher value uses. We were getting underwritten at $2,000 a ton, even though we had contracts with price points 5-10 times higher.”

“Another challenge is that the indoor ag space has fallen out of favor, because people were putting money into companies that weren’t good operators, or good operators were undercapitalized. We need to have more creative capital stacks coming into play.” Dr. Virginia Emery, founder, Beta Hatch

Scaling up insect farming: The hare and the tortoise

One lesson that players in the space have learned the hard way is that things “just work differently at scale, even if you’ve done a whole bunch of work to validate your system,” says Emery.

“It could be as simple as how the water content of your feedstock is different depending on whether you’re getting a truck load versus a train load, so it’s smart to take it slow.”

Meanwhile, what works in one location will not necessarily translate seamlessly into another one, she says.

Mealworms, for example, produce metabolic heat as they are digesting their food, and if you don’t dissipate it, there’s a feedback loop which slows them down, so the design of your climate systems can have a material impact on yields, she notes.

“We intentionally chose our location in Cashmere, Washington, because of the dry climate, so we were able to use evaporative cooling, which is a lot more energy efficient, and has the benefits of also adding some humidity to the controlled environment, which is beneficial for the mealworms’ growth.”

But she adds: “The way that we designed our air handling systems, our HVAC, was not the kind of thing that would translate to a different climate with more humidity.”

InnovaFeed: ‘The race for scale in this industry has put a lot of pressure on companies’

Stepping back, “the race for scale in this industry has put a lot of pressure on companies,” claims Maye Walraven, US general manager at French insect ag firm InnovaFeed, which has teamed up with ADM to build a 60,000 ton/year plant co-located by a corn milling facility in Decatur, Illinois.

“But we have to find a balance between scaling up as fast as possible and making sure that the technology choices we’re making are the right ones. We’ve gone for fairly ambitious size plants, but we’re de-risking them by building them in phases.”

For example, while InnovaFeed has already built a large-scale facility in Nesle, France, this doesn’t mean that it will simply take that template and precisely replicate it for the new site in the US, she says.

“In different locations, emissions from the insects can also be different, so you might need a different HVAC design. Likewise, if your feedstocks are thicker, you might need a different pump system. You don’t want to spend millions on pumps and then have to replace all of them.”

Notably, InnovaFeed’s French facility uses wheat byproducts from a co-located Tereos starch processing plant as its feedstock, whereas the US plant will use corn byproducts, says Walraven, who has spent months building a pilot plant at Decatur that will help de-risk the larger facility.

“What we learn here will determine the size of the factory we need to build. If you have a better yield you can build a smaller factory and reduce your CapEx for the same production output. If the yield is significantly lower [as a result of using different feedstock], you need more space to produce the same amount of protein. So really, the pilot plant in Decatur is key in defining the footprint of the larger factory.”

In France, she says, “we started with a pilot plant in 2017, then in 2020, we launched the first phase of our large-scale factory, followed by the second phase at the start of 2023, and we’ll be launching the last phase in summer this year. We expect that at the end of 2025, we’ll be at our full capacity of 15,000 tons of protein meal per year.”

“Some players made decisions for larger scale facilities based on assumptions that were correct at smaller scale and got their fingers burned. If you’re at the container scale, changing a pump is no big deal. If you’re at a huge scale, that could cost hundreds of thousands if not millions.” Miha Pipan, cofounder, Better Origin,

Does insect farming only make commercial sense at significant scale?

While economies always come with scale, most players we spoke to anticipate that a range of profitable models will emerge in different geographies with different partners.

According to Emery, “If you’re producing insects out of a shipping container, you’re not going to be partnering with ADM, but you might be part of a small integrated farming operation where the farm is trying to upcycle some waste into something that can be used in another part of its operation.

“There was a bit of the, ‘Ours is bigger than yours’ kind of posturing going on in the industry a few years ago, which wasn’t helpful.”

Better Origin is working with vertically integrated UK food retailer Morrisons to process food waste from its operations into protein meal for its free-range chickens using black soldier flies reared in shipping crates, says cofounder Miha Pipan. “We’re not particularly bound to the idea that there needs to be massive scale to make it work. Plus how we do things in the UK won’t necessarily apply to Southeast Asia, for example.”

Kees Aarts at Protix adds: “We’re doing high-intensity controlled environment farming, but we’ve also designed a CapEx solution that can be implemented in the barn of a pig farmer where we would supply the eggs and take up the larvae for processing. The models will be different in different markets.”

As for unit economics, says Walraven at InnovaFeed, “We have the potential to integrate different streams for our insect feed that are currently considered waste that would significantly improve our costs, but there are still some regulatory challenges we need to overcome first.

“We also think we can increase our top line by better demonstrating some of the properties of our ingredients. So for instance, after feeding our ingredients to shrimp, we’ve seen some incredible results in terms of performance, we improved feed conversion rates by 30% and decreased mortality by 40%. But these things take a long time to turn into claims and to demonstrate over and over.”

Large-scale insect farming: ‘It has to be automated, and has to be data-driven’

In many ways, says Aspire Food Group cofounder Mohammed Ashour, insect farming “represents the most ideal case for vertical farming. It’s just a series of boxes with enough food and water to support a certain population. You put the box of crickets on a shelf and you don’t have to touch it again for 30 days. We then utilize an automatic storage and retrieval system like an Amazon warehouse racking system. In this entire [12,000 ton] facility you only need 13-15 operators on the floor in a shift.”

Insect farming at scale, “has to be automated, and has to be data-driven,” adds Marc Bolard, cofounder and CEO at Nasekomo, a Bulgarian startup working with tech giant Siemens to create a standardized insect bioconversion system. “It’s a biological process with millions of correlations, interactions, and dependencies between the animals and their environment. So we’re talking about data collection, data transport, data storage, data security, and the ability to analyze and learn from this data.”

At Protix, says Aarts, “As soon as we think a job is repetitive or that we can control it better, reduce the failure rate, identify outliers, improve the base process and reduce variability, we will automate it. And through that we’ve been able to increase our production, increase our quality, and lower our costs. But we constantly challenge ourselves about what is the right level of automation and what’s the right level of control?”

Entocycle: ‘It all starts with efficient breeding’

But efficient rearing is only part of the picture, says Kieran Whitaker, cofounder at UK-based Entocycle. “It all starts with efficient breeding.”

Black soldier flies, the most widely used protein source in insect ag, he says, live for a few days, mate, lay eggs, and die. After two to three days, the eggs hatch into larvae, which then feed voraciously for up to 14 days until they reach the pre-pupal and pupal stages where they stop feeding. Finally, they turn into flies, and the cycle begins again. Insect ag companies harvest the mature larvae but keep some aside to turn into flies for their breeding operations.

“When it comes to breeding, you want to get as many insects out of the adult population as possible,” says Whitaker, who has developed multiple offerings to help increase the efficiency of insect ag. “So you want to have a very low refresh rate, which means the percentage of insects that are re-used [allowed to hatch into flies for breeding rather than being harvested at the larval stage] should be sub- 5% and ideally 1-2%, which is what we are able to do. This way, the vast majority of the larvae are protein producers.”

According to Whitaker, “There are probably around 1,000 companies in this space now, from startups to companies, that have raised significant funds to scale. Of course, they’re not all going to survive, but you can at least see every country needing one to 100 insect farms, depending on local market demands, and we will service them.”

And whether it’s chickens or black soldier flies, he says, “you can’t farm them without knowing how many you have. Pretty much every foodstuff these days goes through some kind of computer vision sorting machine for counting, grading, and making sure it’s safe or to spec. We’re doing the same thing for insects.

“So the first piece of equipment we’re delivering is a computer vision control system that optimizes for breeding and egg production. So we have a counter that can count 3,000 neonates [early-stage insect larvae] per second and distribute them into any format a customer needs with 95%+ accuracy.”

If you know what you’re dosing, he says, you can then measure how many neonates survive, how many are hatching, exactly what the feed conversion rate is, and make improvements accordingly.

“We can supply companies with equipment or we can help them design and plan a site from scratch where we specialize in the breeding system and Bühler [which formed a partnership with Entocycle last year to reduce time to market for insect farming companies and remove the guesswork involved with in-house systems] handles installation and commissioning of the equipment.”

Whether you are running mega-factories, smaller on-farm factories, or decentralized hub and spoke operations, he says, “you still need quality control. We booked a million dollars in revenue last year and we’re anticipating doing 10 times that this year.”

“What we’re seeing now is large traditional companies moving into the space, whether it’s a supermarket chain trying to meet its waste management requirements, a waste management company that wants an alternative solution to processing food waste, or a food company wanting to find a solution to its by products and a new protein source.” Kieran Whitaker, cofounder, Entocycle

FreezeM: ‘Biology is the major bottleneck of this industry’

As in every new industry, there have been first movers who have had to do everything themselves, and then “as the industry has matured, we’re now seeing specialisms and new business models,” says Whitaker.

One example is Israeli startup FreezeM, which is seeking to disrupt the industry with a breeding-as-a-service model that decouples BSFL breeding from large-scale protein production.

While vertical integration (combining breeding, rearing and processing on one site) might seem efficient, insect breeding and rearing require very different skillsets, says FreezeM, which has developed tech to induce BSFL neonates into a state of ‘suspended animation’ through placing them on an undisclosed substrate.

They are then shipped at room temperature to insect farmers, who ‘activate’ them by feeding them, and have found that the ‘paused’ neonates deliver consistently higher yields than their regular counterparts once they start feeding.

Separately, FreezeM also has a CRISPR gene editing program that edits the genomes of BSF eggs such that the larvae have significantly higher feed conversion rates, delivering a dramatic increase in yield. The new line of gene-edited neonates, dubbed ‘BSF Titan,’ will be commercialized later this year.

The company is also collaborating with the Khalaila lab at Ben-Gurion University on a new technique enabling the simultaneous editing of hundreds of eggs in the ovary of an adult female black soldier fly or pupa via a single injection, paving the way for large-scale editing with the potential for heritable changes across generations, says cofounder Dr. Yuval Gilad.

‘We’ll see a gradual shift from the vertically integrated approach’

“If you look at other established agricultural fields,” adds Gilad, “They are all segmented, because as the industry matures you need to have specialization in each part of the supply chain. Insect breeding requires knowledge of entomology, biology, and biotechnology. The same applies to [other forms of] farming where you have companies that specialize in breeding, genetics and seeds, and then companies focused on farming.

“But in insect ag, almost everyone is vertically integrated, and they all face the same challenges when they want to scale up. So we decided to focus on the biology which we see as the major bottleneck of this industry, and enable others to do the farming in an efficient manner.”

He adds: “There is already big traction from the market and I think we’ll see a gradual shift from the vertically integrated approach that the first companies in the market took. The trend of building the new biggest insect facility is now ending and everybody’s focused on showing revenues and profitability. We can save insect companies all the hassle and risk and CapEx involved with setting up their own breeding hubs.”

While first-generation insect farming sites have breeding operations built in, that will change, he predicts. “When they’re looking into opening new sites, we can help them scale faster and more efficiently. They can also operate a hybrid model where they have their own colony, but they can buffer their production by working with us.”

“If you look at other established agricultural fields. They are all segmented, because as the industry matures you need to have specialization in each part of the supply chain.” Dr Yuval Gilad, cofounder, FreezeM

What business models make the most sense for insect farming?

But what business models are likely to gain traction as the industry evolves? Will large scale plants only get built if they are funded and co-located by large food & ag companies such as ADM, Cargill, and Tyson?

Nasekomo has a demo facility in Bulgaria to showcase its tech and produce small quantities of product, but does not plan to own and operate its own facilities going forward, with CEO Marc Bolard arguing that a franchise model is the fastest way to scale the tech.

Its first (undisclosed) franchise partner, “a green investor,” will open a facility in Bulgaria in 2025, adds Bolard, who says his larvae can feed on a variety of industrial side streams from rice and wheat bran to brewers’ spent grains.

“As a franchisor, we’re an enabler who will deliver our franchisees everything they need to develop and run their operations, from the young insects to the insect building and equipment, to a patented solution to run the bioconversion process with AI algorithms that monitor, alert and improve the process in real time.”

Ideally the franchisee would locate facilities as close as possible to a consistent source of feed such as a food processing facility, says Bolard. But it does not necessarily follow that franchisees will typically be food processors looking to valorize their waste/side streams.

“Most food and beverage companies don’t want to lose focus [by trying to run an insect farming operation on top of the core food business], but they are willing to sign a long-term supply agreement [to provide a feed source to an insect farming facility located nearby].

“So we also need partners that want to develop the bioconversion business and help build a circular economy,” he says. “We’re talking to green investors but also waste processors and waste managers who are ready to invest along with food and beverage suppliers. Another quite different profile of partners is agricultural conglomerates that are in areas such as pig or poultry production.”

Walraven at InnovaFeed adds: “We’re innovators developing new technology and processes, but we may not be the best operator of these plants longer term. There are companies who have decades of experience in operating large agricultural facilities.

“We also need significant CapEx upfront to build these facilities, which is not always easy to secure, so partnerships with large companies such as ADM and Cargill are ways to leverage the strengths of entrepreneurial companies like us and companies that are looking at ways of valorizing their byproducts and securing new sources of protein.

“It’s a symbiotic relationship. We’ve always said our sites will be co-located with large agricultural players both as suppliers of raw materials, but also as customers [for the insect products]. And obviously, ADM and Cargill are also investors.” Maye Walraven, US general manager, InnovaFeed

The way the site in Decatur is currently structured, she explains, “We are the sole owner of the plant, and we have a commercial agreement with ADM to supply the feedstock. But before we can move to this kind of technology licensing model, there is the need to be able to prove the factory economics at more than one plant in more than one geography.”

Ultimately, says Antoine Hubert, cofounder at French mealworm farmer Ÿnsect, which has recently recapitalized and restructured to focus on higher-value petfood markets after raising more than $570 million, “Major agri-food players will be valuable partners to accelerate change.

“On our part, we have made the commitment through discussions with Ardent Mills and Corporativo Kosmos to continue our development through licensing or JV models. This model allows us to both limit costs and benefit from the expertise, raw material supply, and knowledge of local markets of these same players.”

The market opportunity: animal feed and petfood

As for the market opportunity for insect protein, lipids and frass (waste), it’s potentially vast, if you can provide a consistent supply in large volumes, says Entobel cofounder Alexandre de Caters.

“Farming insects at scale is very challenging, but there is more and more pressure on the aquaculture industry to reduce what we call ‘fish in, fish out,’ and I think over time, we’ll only become more competitive, because we see the trend of fishmeal prices going up.”

According to Ashour at Aspire Food Group, meanwhile, “The global petfood category is well over $100 billion and the United States alone represents almost a third of that. It’s a market that is growing quite substantially with a trend towards higher quality, human-grade ingredients.

“One of the really appealing aspects of crickets is that we have demonstrated both in some trials and in the literature, some hypoallergenic effects and gut health related improvements in canines and felines, so there is exciting differentiation that goes a step above protein.”

“The second aspect of insect farming is reliability,” he adds. “Some protein sources for high quality petfood such as venison simply cannot scale beyond a certain level. And third, crickets meet all the sustainability criteria, as buyers are looking for ingredients that can help them reduce their carbon emissions.”

According to Walraven at InnovaFeed, “Developing the US market will be key, especially because there are segments here that don’t really exist in Europe, for instance, the more premium petfood segment and the backyard poultry segment.”

As for animal feed, she adds: “We’ve always seen aquaculture as a very strategic market because it is facing a mid-term protein deficiency and the price of fishmeal has doubled over the past 18 months, so buyers are very aware of the need to secure new sources of protein.

In segments such as shrimp or poultry, meanwhile, she says, “It’s more about targeting health benefits and performance aspects that the ingredients can unlock.”

InnovaFeed has “several long-term offtake contracts” with Cargill, ADM and others, sats Walraven. “I’d say 75-80% of our volume over the next years is locked up in these contracts.”

‘We saw what happened when just one boat got stuck in the Suez Canal’

According to Whitaker at Entocycle, recent supply chain shocks have further bolstered the case for insect protein: “We saw what happened when just one boat got stuck in the Suez Canal, then we saw the impact of CODID-19 on global supply chains, the war in Ukraine, and then the events in the Red Sea, flooding in Brazil, El Nino in South America, all which causes volatility in terms of protein supply.

“Then if you look at the long-term trends, the soy protein growing regions of Brazil in Argentina are going to suffer severe drought. Meanwhile, fishmeal is a slowly dwindling stock. All this has prompted a lot of countries to develop food protein strategies as part of food security efforts and we’re going to see a lot of onshoring.”

Ÿnsect, which is currently focused on scaling its farm in Amiens, has “signed contracts worth around $200 million, primarily with players in the petfood sector,” says Hubert. “In January, we also received approval from the AAFCO [which regulates animal feed and petfood in the US] for the commercialization of one of our ingredients (Protein70) for use in adult dog food in the US.”

At US-based Chapul Farms, adds founder Pat Crowley, “One market that is endlessly interesting to me is the backyard chicken market, which really grew during the pandemic. The benefits of black soldier fly larvae as chicken feed are tremendous: healthier eggs, healthier feathers, and we’re seeing great work now on the immunological benefits.

“Another interesting market is trout production in the US, where they haven’t really been able to get fish meal—herring, anchovies and so on—out of the diet,” says Crowley, who introduced many Americans to the concept of eating bugs back in 2012 with the launch of cricket-fueled Chapul bars, but has since switched his focus to designing, building, and operating commercial scale BSFL facilities.

“And those populations aren’t increasing, so there’s this massive need in the industry for alternatives. Black soldier flies have a similar amino acid profile to fishmeal and there’s also some exciting academic work looking at how feeding them to fish gives them a healthier gut.”

“We think that the human food market for edible insects will develop over time, but it will probably take five to 10 years, as there are still big challenges in terms of regulations, acceptability, and palatability.” Maye Walraven, US general manager, InnovaFeed

Insects and the circular economy

Ultimately, says Crowley at Chapul Farms, what makes insects so exciting is that they “have this incredible capacity for circularity: they leverage millions of years of microbiological evolution to process organic material into healthy protein and fat, add microbial life to soil, eliminate food waste, decrease agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and our reliance on fossil fuel and unsustainable inputs in agriculture.

“You have US states saying we’re going to halve our organic material going into landfills, for example, but there’s not really a definitive plan for how they’re going to do that. Insects can fill that role right now.”

Beyond protein: ‘We envision a future where insects power our healthcare and electronics’

While most players in insect ag are focused on proteins and lipids for feed and fertilizer, several startups are exploring their potential in other areas, with Canadian startup Future Fields deploying genetically engineered fruit flies to make pricey proteins from FGF2 to transferrin; and India-based Arthro Biotech exploring the potential of insects to make biopesticides, nutraceuticals, and biopharma products.

Singapore-based Insectta, meanwhile, is targeting higher-value markets such as healthcare and electronics with melanin and chitosan from black soldier flies. “In a nutshell, we envision a future where insects power our healthcare and electronics,” says cofounder and CMO Chua Kai-Ning.