Since insulin produced by genetically engineered bacteria—rather than the pancreases of slaughtered animals—was first approved in 1982, the market for ‘biomanufactured’ products produced by microbial, animal, or plant cells has grown rapidly.

“But in areas other than pharma—whose business models are built on high-margin, low-volume products with low sensitivity to costs—innovations have created only niche markets in enzymes, fragrances, and food and feed supplements,” concedes a recent report from Synonym and Boston Consulting Group.

So what will it take to make the economics of precision fermentation stack up for a wider range of bioproducts such that they can compete with low-margin, high volume products derived from petrochemicals or industrialized animal agriculture?

And who is going to fund the infrastructure required to underpin all this?

The ’scale-cost paradox’

Attendees at the SynBioBeta conference in San Jose touted a variety of solutions to drive efficiency in biomanufacturing, from new tools to domesticate a broader array of microbial hosts (Wild Microbes), to cheaper and more sustainable feedstocks (Hyfé), cell-free production (Debut), continuous processing (Pow.bio, Cauldron), novel bioreactor designs (Sterling Bio Machines), AI/ML to help optimize cell lines and bioprocesses (Triplebar), and more productive cells (Enduro Genetics).

In some cases, the unit economics may already stack up pretty well with existing tools, but only if firms can operate at significant scale, said Synonym cofounder Joshua Lachter in a session addressing the ‘scale-cost paradox’ facing many startups. In a nutshell, he said, it’s the classic chicken and egg situation. They lack the scale to compete, but struggle to finance large-scale production without being able to show there is solid market demand for their products.

According to Lachter: “We need corporations to actually make commitments to the products [via firm offtake agreements] that will allow them to fulfil commitments they have already made [to make more sustainable products]. We also need governments to catalyze demand.”

But precision fermentation startups also need to inspire more confidence, said Synonym chief investment officer Brentan Alexander in a panel session during the conference: “We encourage everybody to do TEAs [technoeconomic analyses] early and often. We see a whole lot of companies that do TEAs and then are very surprised about what their costs will actually look like at scale. And if you pick the wrong target, or you have a bad idea of what [costs] you actually will be able to produce at, you’re going to be in a world of hurt in a couple of years.”

As Matt Gibson at precision fermentation startup New Culture observed during another panel debate, founders have to “convince investors that the technical risk is low and the market opportunity is super-high.”

And with VC funds largely unwilling to fund CapEx projects in the current environment, he added, “You have to make your business model work with a CMO [contract manufacturing organization]. And you have to develop and optimize your process before you can think about building your own facility or working with a strategic.”

“Synonym has designed a highly standardized facility for which 80% to 90% of the capex goes to facility elements that are applicable across many precision-fermented products. Only 10% to 20% is for molecule-specific equipment. As a result, investors and funds that specialize in infrastructure investments can approach biofoundries as a single asset class in which each project has similar specifications and requirements.” BCG/Synonym report, Feb 2024

Biomanufacturing capacity: Legacy CMO network is ‘not making products at the scale or cost structure that’s needed’

One challenge, said Lachter at Synonym, is that CMO capabilities vary pretty widely: “Fermentation right now is looking a lot like the early days of the information revolution, where before you had data centers, you literally had companies in Silicon Valley that were hooking up computers in basements with wires and there was no standardization. And fermentation looks like that today, you go to any CMO and they all have different capabilities, different tanks, sizes, different everything.”

Mark Warner, founder at Liberation Labs, which is building 600,000-liters of new ‘fit for purpose’ biomanufacturing capacity in Indiana, told AgFunderNews during the event: “The current network out there today is a legacy network. It averages 40-50 years old and it was built for other purposes, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, biofuels. It can make the products that these new technologies want to make, but it’s not making them at the scale or cost structure that’s needed.”

He added: “Food products, especially commodities like whey, are challenging, and need probably the bigger facility we have planned to really get cost parity. But there’s a lot of other products, materials, infant formula components, agricultural biologics, that are already very profitable both for us and for the end user today.”

The investment landscape: ‘Assume 2024 is going to be a bloodbath’

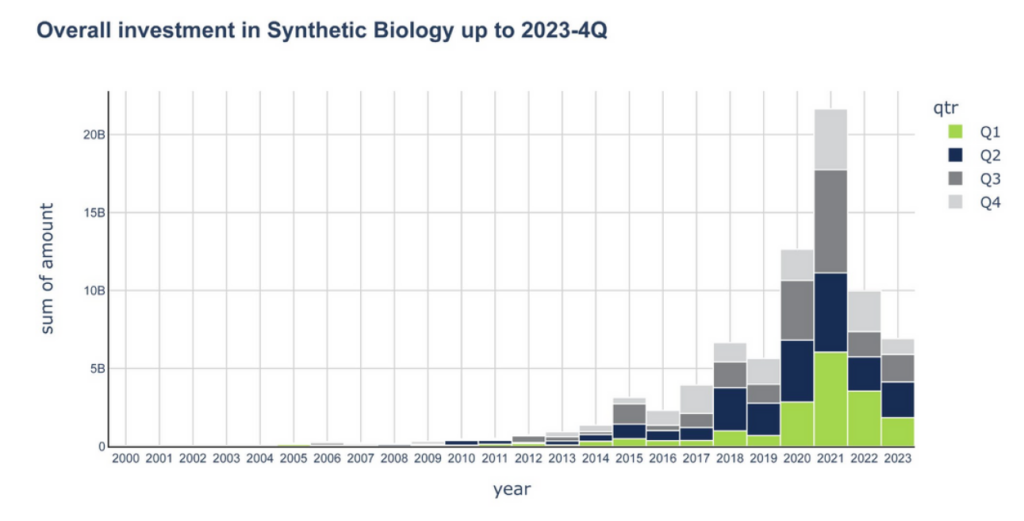

Synthetic biology startups attracted $6.9 billion of investment capital in 2023, a 31% decline versus 2022, mirroring the downward trend experienced across multiple sectors, according to a recent report from SynBioBeta and tech consultancy Futurity Systems.

However, funding in 2023 was up vs 2019, noted SynBioBeta founder Dr. John Cumbers during a webinar held just before the conference. “If you take out these pandemic peaks [which were especially inflated for synbio companies given the interest in vaccine production during the pandemic, he said] then the chart looks linear.”

However, there’s no guarantee that things will improve this year, cautioned Futurity Systems cofounder Mark Bünger, who told startups attending the webinar: “If you raised money three years ago, this is going to be a pretty tough year. There’s less appetite for risky things because you can get a [decent return] just by putting money in the bank. So assume 2024 is going to be a bloodbath. If it’s not, at least you’ve planned accordingly.”

AI and engineering biology: ‘We’re seeing a ton of investment in this area’

As for where the money is going in synthetic biology, said Bünger, “Enabling tools [tech for reading and writing DNA, computer aided design for genes and genomes, cloud labs, automation and hardware tools, organism engineering platforms] drove a lot of the growth in the early years. But what’s happening now is we’re seeing more investments in applications, in companies that are applying these tools. And then I expect we’ll see a new wave of technology or tools to drive this industry forward again. And one of the areas where that’s happening right now is in the use of AI in synthetic biology.

“Just look at AI for protein folding [AI tools such as AlphaFold can predict how proteins fold from a chain of amino acids into 3D shapes that in turn are predictive of what kind of functionality proteins will have]. That saved trillions of dollars of what would have been grad student labor.”

Cumbers added: “If you think about the companies that are doing protein engineering or antibody engineering, and companies like Cradle or Absci, there’s a ton of great talent in this area at the intersection of software and biology, and it’s not surprising that we’re seeing a ton of investment in this area.”

Financing biomanufacturing scaleup: ‘We’re just fundamentally missing an asset class’

Exciting though AI might prove to be in improving the efficiency of biomanufacturing, however, we still need capital to put steel in the ground, noted successive speakers at the event.

And right now, that’s pretty tough, said Laura Turner at Agronomics, a London-based publicly listed company and an investor in Liberation Labs.

“In terms of finding the appropriate capital providers for projects like this, there are not many VCs that are willing to underwrite that. They’re much more comfortable focusing more on the upstream, the bioprocess, and so on, so finding sources of capital at this juncture has been a challenge.”

Zak Weston, a partner at investment consulting firm BERA, added: “I think we’re just fundamentally missing an asset class, in that venture capital is really well adapted to taking early-stage venture risk and funding certain kinds of SaaS businesses. But it’s poorly suited to building the types of facilities we need, even in some cases at demonstration scale, but particularly for first commercial scale.

“At the early stage, we have VC, and once companies mature, there are many options on both the equity and the debt side. But in the middle, there’s just nothing that really suits.”

Turner at Agronomics added: “There’s government funding available for scale up or R&D, but as we’re getting to this point of companies getting commercial contracts and really expanding that’s where the government needs to start playing.”

“Serving a $200 billion market for products from precision fermentation by 2024 would require a 20-fold expansion of current production capacity. By 2040, the world will need 6,000 new fermenters spread across 1,000 biofoundries that have 2.4 billion liters of total capacity. Supplying the primary feedstock, sugar, would take 40,000 square miles or roughly equivalent to the land mass of Bavaria or West Virginia.” BCG/Synonym report, Feb 2024

Investor: ‘I think we’ve kind of failed in this space’

Speaking on an investor panel at SynBioBeta later in the week, Genoa Ventures managing director Dr. Jenny Rooke said: “I think we’ve kind of failed in this space. I’m not sure that venture investors have figured out how to help entrepreneurs choose winning business models that correlate with venture returns so that we can keep putting venture capital into the space.”

Fellow panelist Dr. Omri Amirav-Drory, general partner at seed investor NFX, added: “You have to be so careful with the numbers in biomanufacturing. If you’re wrong, when you scale, you’re multiplying how wrong you are. The problems just get bigger.”

He added: “We only invest in platform technologies. This used to be the thing two years ago and it’s kind of being poo-pooed, they say, you need to have products, but for me, you cannot create good products if you don’t have a good platform.”

Cheaper feedstocks, continuous processing

So what are these platform or ‘enabling’ technologies that will transform the unit economics of biomanufacturing?

According to Dr. David Welch, cofounder and chief scientific officer at foodtech investor Synthesis Capital, attention is increasingly turning towards circular processes that utilize side streams from multiple industries to serve as more sustainable feedstocks.

We can’t rely on corn dextrose to fuel every fermentation process, he told SynBioBeta delegates on the last day of the conference. “We need new microbial strains that are more efficient at producing different types of proteins and that can utilize non-conventional feedstocks [from carbon dioxide or methane sourced from waste industrial gases to lignocellulosic sugars contained in agricultural side streams such as sugarcane bagasse and corn stover].”

Moving from a batch to a continuous process can also enable firms to cut costs by using smaller, more efficient bioreactors to achieve the same output, Pow.bio cofounder and CEO Shannon Hall told AgFunderNews at the conference.

“Capacity alone cannot fix the core problem of lowering unit costs. The right target is economic viability, and hitting it requires technical advances in biomanufacturing.” By running a fermentation process more like an assembly line, said Hall, “We see multi-fold increases in productivity without contamination or drift.”

Novel microbial hosts

At fellow startup Wild Microbes, meanwhile, founder Dr. Tim Wannier is working on methods to domesticate wild microbes that may be better suited at expressing certain proteins or utilizing alternate feedstocks than the handful of microbial workhorses powering the bioeconomy today.

He told AgFunderNews: “There are large strain collections out there… but the real trick is moving from a collection of disparate microorganisms into a stable of [potential hosts] that are well-trained and ready to scale.

“Say you have a wild organism that you isolated from a saltwater marsh, and you culture it in the lab. In what we call phase one, you need to figure out how to put new DNA in and make one modification to the genome. Phase two is that once you can make one edit, how can you then go from a very low throughput technique, which is traditionally where a lot of microbiology labs have stopped, to be able to make billions of edits across a population of cells? And that’s where Wild Microbes has a unique perspective…

“We have an approach [recombineering] that relies on a set of very high throughput tools derived from bacteriophages and they allow us to make billions of changes across the population of cells. The goal is to get to library-scale engineering in wild hosts.”

More productive cells

Danish startup Enduro, meanwhile, has developed tech it claims can significantly increase biomanufacturing yields and prevent declining production at scale by “addicting cells to high production.”

In any bioreactor, only a certain percentage of cells actually produce what they have been programmed to express, while the rest are essentially freeloaders, consuming valuable feedstocks without producing anything useful, CEO Christian Munch told AgFunderNews at the sidelines of the conference.

Yeast and fungal cells do not naturally produce dairy proteins such as beta-lactoglobulin, he observed, so there’s “no evolutionary competitive advantage” to making it.

In a bioreactor, he observed, “sometimes only 15-20% of the cells are responsible for producing your target product. After 60-80 generations, the cells may completely lose the ability to produce. For each generation, there are mutants that say, ‘Hey, if I throw away this beta-lactoglobulin production gene, I can grow faster,’ and they will ultimately take over the bioreactor.

“What we do is effectively trick the cells into thinking that they have to produce the target substance in order to survive.”

Enduro links the expression of essential genes [which are critical for the survival of an organism] and production of the target substance in a cell. “Our solution is a genetic biosensor or promotor that couples with that essential gene in the cell and that means that only cells that produce the target substance can grow or proliferate.”

He added: “The essential gene is upregulated when it produces the target substance and downregulated when it doesn’t.”