Editor’s Note: Agrifoodtech investor PeakBridge funds startups from seed stage to series B in five categories in the US, Europe and Israel: ingredients innovation, alt protein technologies, digitalization and food systems 4.0, nutrition & health, and alternate farming systems.

The views expressed in this guest commentary are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of AgFunderNews.

Foodtech is at a crucial tipping point, and with tipping points come opportunities. But the real potential of this space has gotten muddled, and it’s a good time to cut through the noise.

A fair amount of hype and non-expert takes have painted a picture of a new, entirely high-risk sector defined solely by alternative proteins. None of that is quite right, and reality is in fact rosier – particularly for forward-thinking investors.

Let’s rewind for a moment. Food is a $9 trillion industry that quite literally touches every one of us, every day. Innovation in the sector has been ongoing for decades, helping give rise to multi-billion-dollar CPGs and specialty ingredient players. Alongside that has been growth in dealmaking, with nearly all major private equity houses investing without high capex or particularly high risk.

Then, in the past 5-10 years, came an upheaval – and a world of possibility. Advanced tech from information technologysensors, satellite data, and robotics) and biotech (Crispr, precision fermentation, and cell culture) entered the game, turning foodtech into what it is today: a serious, scalable VC play. AI will take it further, faster.

Add to that a global shift in consumer behavior, with growing demand for health-conscious, sustainable food options, as well as growing urgency to address food security and climate change, which by now has resulted in governments spending billions to mitigate these existential risks.

Now the time has come to make the leap forward. Many worthy foodtech companies have already done their core R&D and jumped through the regulatory hoops. The next 1-3 years are a crucial timeframe to move out of the lab, and into the real world. And with the right approach, that doesn’t require high risk or high capital, even in today’s inflationary environment.

Exit strategies

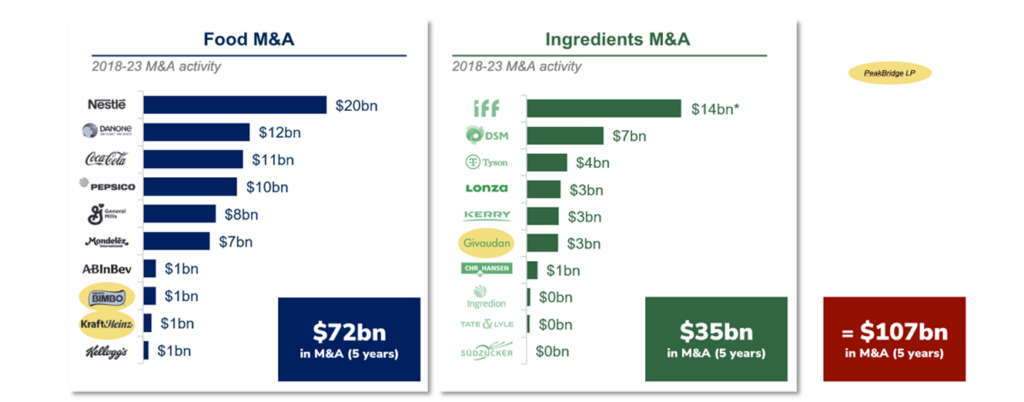

The upside for investors is substantial, and it’s not centered around IPOs. Instead, M&As and exits via trade sales to strategics are the more likely path, thanks to the massive global food industry.

Food corporates spend just 0.4% of their revenue on R&D, compared to software at 18% and pharma at 12%. In absolute numbers, the top ten food and food ingredient companies spend just $4-5 billion a year on R&D, and an average of $22 billion a year on M&A.

Corporates and their big-name brands aren’t built for risk or, frankly, for ground-up innovation. But they can’t afford not to innovate either. Their preferred path is to let someone else do the trial and error, scale, and buy them out. And that equals significant ROI potential.

Debunking the myths

When we talk about scaling up foodtech, the big barrier to cross is high capital expenditure. Scaling can often require boosting production volumes of ingredients and enabling technologies, which in turn demands equipment and sometimes entire greenfield facilities, along with the supply chains and specialized labor to operate them. While the last few years of branding hype have skewed the conversation, not all foodtech requires sky-high capex.

Foodtech ≠ alternative proteins

This sector goes far beyond alternative proteins, though reading about it you might not be able to tell.

Bulk, animal-free proteins often demand hundreds of millions in capex; but there’s a wide range even within that space itself – areas of high impact potential that require far less capex and risk. Take alternative dairy: its production is better established and is based on key ingredients far less expensive to replace (dairy is almost 90% water).

The global plant-based milk market is expected to surpass $123 billion by 2030. For added perspective, in the Western world alternative dairy makes up some 16% of the market, compared to just 0.5% for alternative meats.

The focus of innovation now needs to shift towards better taste and sustainability, like what Austria’s Kern Tec is doing with their plant-based milk derived from fruit seeds. Processing these readily available sources requires significantly less capital investment than the high upfront costs associated with novel feedstocks, which can range from specialized processing equipment to lengthy regulatory approvals.

Reasons to look beyond just alternative proteins go farther.

We have a mounting dietary fiber gap, we waste one third of our food across the supply chain, and we urgently must create more resilient production systems for food ingredients. All these areas have different business models, unit economics and Capex requirements – while sizably contributing to better food systems.

Foodtech is also about saving food

When looking for relatively low risk and high scaling potential, we should also be thinking not just about what new proteins and food to produce – but at how to save what we already make. One of the biggest (and most expensive) problems in the food system is the massive amount of food waste across the supply chain. 1.3 billion tons of food are wasted every year.

Smart tech solutions integrating AI and imaging allow for scalability without a large investment in capex, IP, and regulation, since we’re reducing things that have already been produced and exist in the market.

New solutions, old tech

The message of ‘disruptiveness’ gets thrown around a lot, but many companies are in fact deploying proven technologies where both technical and engineering risks have already been addressed in other industries. Take The Mediterranean Food Lab, a company reinventing food flavor.

Their team found a clever new tech-driven new approach to apply a centuries-old process used for making things we all regularly consume like soy sauce: solid-state fermentation. Cases like these using validated tech don’t face the same hurdles seen in spaces like cultivated meats. That means they’re ripe for scaling, without extraordinary capex. In short, more bang for your [less] buck.

There’s always a way

No matter the capital intensity of the business, investors and founders can and do find clever ways to mitigate them. Those include road mapping to identify when Capex investments are truly needed to de-risk the next phase in go-to-market and attaining off-takes. Or forging partnerships within the supply chain, from farmers to industry partners.

For another approach look no further than cell culture, where huge pushback has surrounded a lack of affordability. By targeting high-value species, companies can reach scale and unit economics, building a solid business case along the way. Doing so lays the foundation to then scale more broadly into lower value species.

The key to getting it right: Unit economics

In food and foodtech alike, rigor around unit economics analysis is key. Scaling up a new process is crucial to proving unit economics and securing hard customer traction. The typical catch-22 mantra of “we need scale to serve customers, and without customers we can’t raise financing to scale” is too simplistic.

First, unit economics reveals true technological innovation and competitive advantage. Gross margin makes the difference between temporal and sustainable revenue growth. Growing a foodtech business with positive unit economics means a company has found and proven a way to translate technology into a cost and/or a market share advantage.

It’s hard to escape the required operational expenses to scale a business (and legacy players will often hold scale advantage around such expenses). Above-expected gross margins are a sign of a true sustainable advantage.

Second, kicking the can down the road just doesn’t work. Yes, economies of scale matter. But achieving critical technological metrics is key to getting it right, before raising hundreds of millions in funding to scale capacity. This requires businesses to carefully consider which product-market combinations to target. Climate-controlled indoor agriculture economics are more favorable to, say, vanilla than lettuce, for example.

It also requires detailed and honest assessment of scale-up pathways. Proving feedstock efficacy, unit operations and yields (i.e. critical drivers of many cost of goods structures) at more modest volume increases – for example through co-manufacturing partners – allows founders to de-risk their process and unit economics ahead of those mega rounds for big capex projects.

Here too, we need to look at the broader foodtech picture to identify those companies with proven, positive unit economics in their current scale of production.

A stage set for deals: ‘Strategics have record levels of cash on their balance sheets’

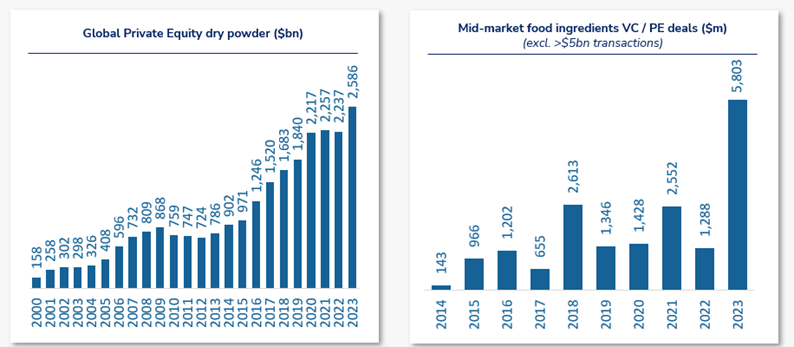

The last five years have seen a rich dealmaking environment growing steadily, with healthy returns in private equity and strategic M&A. Funding has flowed into the space to scale up innovative startups, coming from early-moving institutional money, emerging specialized investors, sovereign funds (such as Temasek, GCC, and SWFs) and select food corporates willing to finance heavier capex for a bigger payoff (such as JBS, Tyson, and ADM).

To understand just how resilient the deal making environment is, look no further than ingredient companies, where investments and exits across maturities have been steadily growing over the last seven years. They’ve shown remarkable resilience, emerging relatively unscathed through a pandemic and conflict.

Strategics have record levels of cash on their balance sheets and free cash flow built up on the back of strong financial results. They’re also quickly pivoting to meet consumer preferences, investing in natural and clean-label products.

As JP Morgan noted in its January 2024 report, “Innovations for large ingredients strategics in 2024 are situated in the bio-based, sustainable nutrition/solutions and health & wellness space, thereby supporting FMCG sustainability commitments and regulatory requirements, and we expect those customers to step-up innovation/product launch mode.”

Sensient, Symrise, Givaudan and Ingredion are among those who have ramped up investment in plants and other facilities; with IFF, DSM, Huber and many more among those closing M&As to fill portfolio gaps.

Others are also increasing their exposure to the plant-based space, aiming to develop the next generation of products with better taste and texture. ADM, Cargill, and Bunge have spent hundreds of millions on production and processing facilities. Others are leveraging M&A to add new capabilities, with further consolidation of plant-based ingredients expected.

Food ingredients have also drawn greater focus in private equity, with many new platform investments seeking bolt-on acquisitions and boasting a record $2.60 trillion in dry powder as of 2023.

What is likely to change? The types of acquisitions: Value creation from large-scale deals is somewhat limited and affected by interest rate hikes, so it’s small to midsize strategic acquisitions that are expected to gain more focus in 2024-25 – and have historically proven more beneficial.

Closing the gap

Yes, there is still a funding gap, and filling it is essential to pushing the right companies to the next level and getting to price parity – so that ‘nice to have’ technology can become a scalable solution with global impact.

Generalist investors can play a significant role in making that happen, yet they often aren’t inclined to focus on foodtech given the field’s fast-moving developments and technical complexities, with less familiar risks that are therefore harder to manage.

Yet generalist funds simply don’t need to master this space on their own. Instead, clever strategic partnerships with sector experts can unpack the different layers of perceived risk, from commercialization to scaling up production.

Take for example food ingredients like fungal proteins. Those might not have been produced at scale in the past, but their production technologies and required infrastructure have seen large-scale validation in adjacent industries.

Once those scale-up risks are better understood and technical milestones achieved, financing a scale-up operation becomes an assessment of market risk more than technical or production risk. When it comes to commercialization, smart commercial partnerships can similarly clarify the associated risks – along with the true potential for attractive returns on such investments.

The takeaway?

Foodtech’s time has come to make the leap forward, and cutting through the noise reveals a different reality than most have come to believe: a veteran industry powered by information technology, biotech and AI; bold companies ripe for scaling, and a global environment that demands nothing less.

This is an emerging asset class with substantial opportunity. With the right guidance and expertise, we can bring tech to bear and make returns – in one of the biggest global markets in existence: food.