Liberation Labs — a startup aiming to address capacity bottlenecks in biomanufacturing — has secured a $25 million government-backed loan to support its first commercial-scale precision fermentation facility in the US.

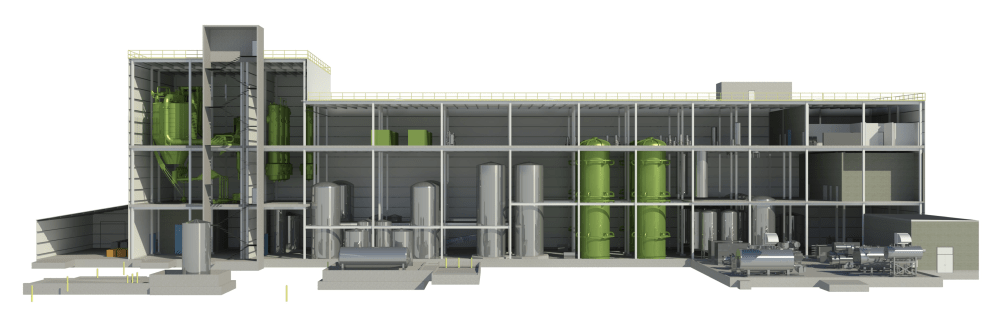

The purpose-built site in Richmond, Indiana, will have 600,000 liters of capacity and is set to become operational by the end of 2024, said the firm: “The plant will produce bio-based proteins and other building block ingredients at a scale and cost that will fill a pressing need among both new and established consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies and other industrial manufacturers.”

The USDA business and industry loan—designed to spur economic development in areas with fewer than 50,000 residents—has been structured by Ameris Bank and offers “continued confirmation of the importance of adding biomanufacturing capacity in the US as well as the strength of our business plan,” said Liberation Labs cofounder and CEO Mark Warner.

“Our project underwent significant due diligence and risk rating, and to come out the other end with a loan guarantee is a strong reflection of the quality of our team, our vision and our ability to execute.”

Footings were installed in August and concrete poured in September. All long lead equipment has been ordered and is under construction, while the company has continued to build out its corporate staff and local team, added Warner.

“The loan guarantee ensures Liberation Labs will continue to have access to capital necessary for other ‘bricks and mortar’ needs of the site.”

Series A in progress

Warner, who previously told AgFunderNews that it would take $115 million to get the site in Indiana up and running, has thus far secured $20 million in seed funding [from investors including Agronomics and CPT Capital] and $30 million in equipment financing, plus the new $25 million loan. He is currently raising a series A round to secure the remaining funds.

“We’re in the late stages of a series A fundraise that we hope to close in the first quarter,” said Warner, a former chief engineering officer at Impossible Foods who has worked with dozens of startups in the precision fermentation space in recent years via his consultancy Mark Warner Associates. “There is still money out there for credible ventures, but investors are looking for higher probability of getting to cashflow positive or profitability in the near term.

“The other thing that’s been interesting is that two years ago, if you were to pitch something that involved a significant capital asset, it was not that interesting [to many investors]. In today’s environment, they still want that infrastructure to give returns that look more venture-like which we’re confident we do, but it’s seen as a positive where that may not have been the case two or three years ago.”

Fit for purpose biomanufacturing facilities

While there is a well-publicized lack of biomanufacturing capacity in the US, said Warner, “what matters is whether the capacity is fit for purpose. I always say we can make these products, but we’re not making them at the price points that are getting wide enough acceptance.”

He added: “The easiest way to explain it is that people are currently trying to manufacture food in 50-year-old pharma facilities, with a cost structure that was never designed for food.”

The new Liberation Labs facility is fit for purpose, he claimed. “It’s a combination of things. It’s about the design of the fermenters, oxygen transfer rates, our ability to run sterile batches, the efficiency of our downstream processing… A lot of the filtration equipment we’re using wasn’t available 50 years ago. We also cover the end-to-end process from sugar [as feedstock for the microbes used as production organisms] to the final product. 80% of CMOS out there don’t have spray dryers on site.

“We can also run a much broader range of organisms than the majority of the contract manufacturers out there. Methanol-fed Pichia [yeast] is a perfect example. There is no facility of any size in Capacitor [an online repository of global fermentation capacity built by Synonym Bio] that was ever designed to make methanol-fed Pichia, although there’s a handful that have been retrofitted to do it the best they can.”

Liberation Labs’ pricing structure “isn’t that different than the CMOS out there as far as cost to use our facility per month,” he said. “The difference is, we’re designed to make twice the product. Most of the numbers we’ve seen when we’ve quoted larger clients are minimum 30-40% lower than they’re seeing on their existing all-in manufacturing costs.”

Demand exceeds supply

With more than 12 months to go before the facility is operational, Liberation Labs has “way more interest than the capacity of the facility,” claimed Warner. “We’re confident we’re going to be able to get a credible binding offtake for a baseload on the facility that will support our fundraising and initial operation.”

As for the type of partners interested in using the facility, he said, potential clients range from companies looking to produce high-value ingredients for infant formula and cosmetics to specialty enzymes, spider silk [proteins], and ‘animal-free’ dairy proteins.

Asked about the technical competence of some of the precision fermentation startups Liberation Labs is talking to these days, he said: “Two or three years ago, startups would tout their titer [the amount of an expressed target molecule relative to the volume of liquid], but not necessarily the overall process and economics being ready to commercialize.

“What we’re seeing today is a larger number of companies that have run at significant scale that gives us enough comfort that their processes are ready for commercialization, whereas a few years ago, there were more technical risks.”

Further reading: