While still a student at New York University, David Ahmed used to watch growers coming to and going from the farmers markets in Manhattan. Sometimes they left with empty trucks; other times, the vehicles were still full of produce.

Believing there was a better way to produce food and, more importantly, forecast how much growers actually needed to produce, Ahmed formed hexafarms in 2019 with Felix Kirschstein, Huijo Kim, and Abraham Hdru.

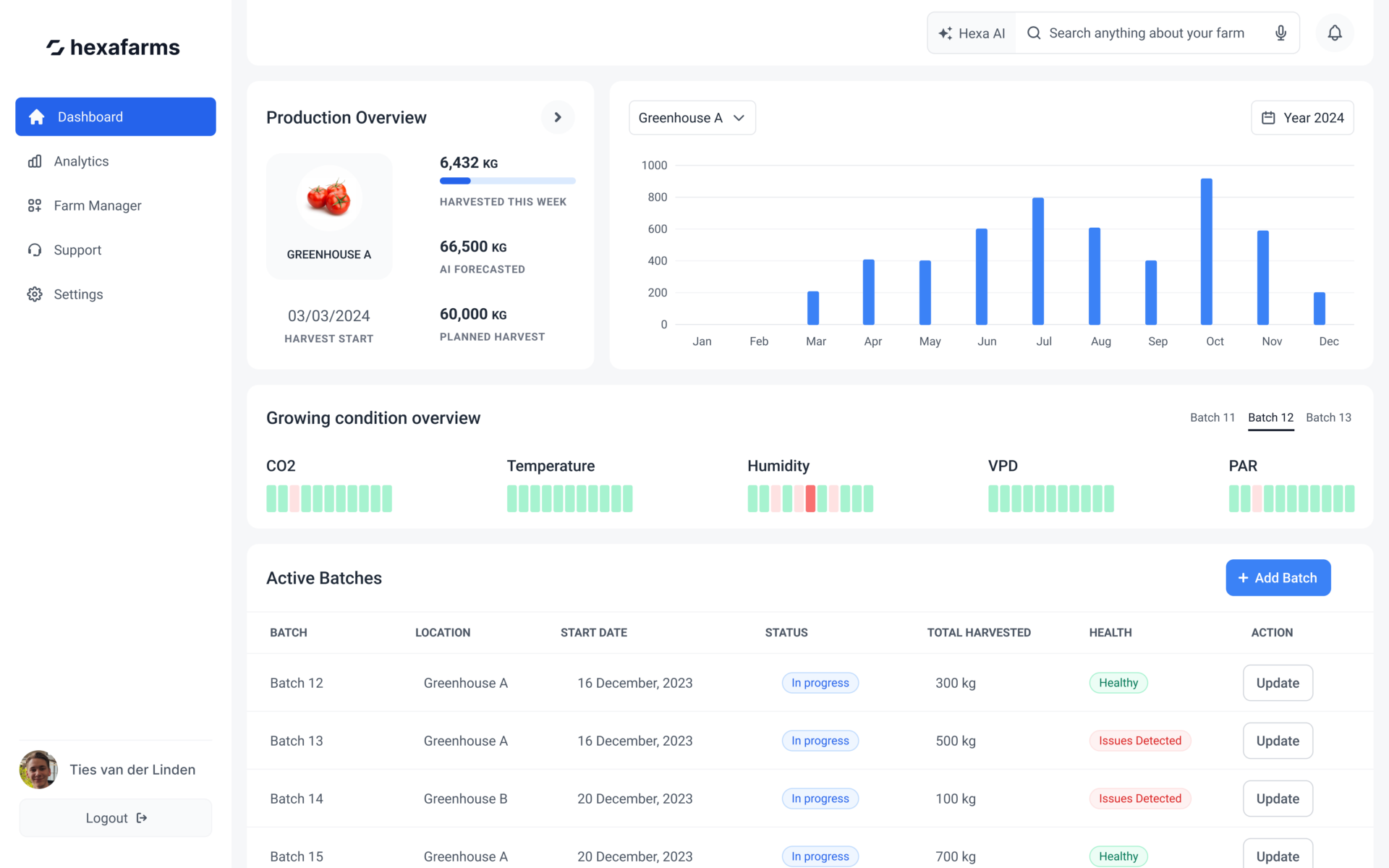

Today, the company offers yield forecasts, climate monitoring, fruit counting and other things for greenhouse and indoor farm growers, using sensor technology and AI to track the entire farming environment. Its long-term goal is to build a machine learning model that can, in any growing environment, surpass humans when it comes to optimizing production.

“The system is quite dynamic,” Ahmed tells AgFunderNews. “With just the collected data, it’s able to tell the growers how much they [will] harvest weeks in advance. Since we know this, the next step is to also give actionable strategies to growers to get the most out of the resources they put in.”

Based in Berlin, Germany, hexafarms just raised €1.3 million ($1.4 million) in pre-seed funding led by Speedinvest, with participation from Mudcake and Techstars,

Below, Ahmed (DH) chats with AgFunderNews (AFN) about the future of indoor ag, what sets hexafarms apart, and why sheep and AI don’t always mix.

AFN: What does hexafarms provide for growers?

DA: We have cameras and sensors around the farm and harvest record data from growers. The system is quite dynamic — with just the collected data, it’s able to tell the growers how much they [will] harvest weeks in advance. Since we know this, the next step is to also give actionable strategies to growers to get the most out of the resources they put in.

The ultimate “Holy Grail” is that we want to push the limits of AI and machine learning in the ag space. With all due respect, when we talk about the status quo of machine learning in ag, it’s just statistical methods, and that’s not going to work.

We work with 14 different growers, each with a totally different farming setup, and it’s one machine learning model. So the goal is that once we have seen the patterns, the machine will be actually much better than humans in terms of optimizing production in real time.

AFN: Why did you start the company?

DA: I was working with farmers in Upstate New York who would go to Manhattan farmers markets. Sometimes they left with empty trucks, sometimes the trucks were full of cabbages. I thought, “This is not going to work and we need to do something else.”

I started asking the fundamental question of how we can improve food production, but I found that there was a fundamental problem with all the existing approaches — at commercial scale, plant biology was the last thing that growers were optimizing for. Once you dig a bit deeper, you will find that there’s so much to optimize for.

After the 1960s and 1970s, besides the introduction of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and controlled irrigation, nothing really drastic has changed [in commercial food production]. It became my mission to mark the Fourth Green Revolution by leveraging digital technologies in a very affordable fashion to cater to the needs of millions of plants in real time.

I knew I was not the first one to think about this — look at all the greenhouses out there, all the indoor farms. But I thought we could tweak and tune things and get a lot more production out of farming. We are seeing that there’s still 30% that growers leave on the table.

[The company] started in 2022. We went through the Techstars Berlin program. Then we went out to greenhouses to observe what our ideal market was. Now we have more customers than we can handle. By the end of 2024 we are expecting to have processed about 25 million kilos of tomatoes and strawberries with our system.

AFN: How is AI in your technology providing benefits to growers and others in indoor ag?

DA: Let’s say you are growing tomatoes. Right now what we provide is a short-term view, like forecasting something that already sells like crazy.

This is a typical case with one of my customers. They had 5 million euros before they started the season and had to grow X amount of tomatoes to supply to supermarkets. So they got the money and they have to produce the tomatoes. They need to know what production will actually be like, sometimes within a few-hundred-kilogram margin. There are three to four chief gardeners on the farm, and they look at production to predict it. They have to count fruits and flowers and a lot of things you don’t see. But they’re never right.

Now comes hexafarms. We have these cameras, we have several sensors, and the models basically look for the increase or decrease in fruit and flower counts. We look at the historical data, the permeability of your greenhouse, like how UV radiations are acting.

We don’t hard code these rules, either. We do not put in place something like, “These are five variables that you have to look at.” We’re like, “Here is a lot of data and here’s a human expert and a historical record”; now the algorithm has to come up with a way to understand the production itself.

So far, this approach is working really well. As we gather more and more data, we will easily be able to surpass the known limits so far.

Computer vision extracts food counts, flower counts, leaf area index, etc. In terms of the model performance and benchmark, we use literally anything out there in terms of computer vision. The system can then tell you that in one day you’ll have this much yield, next week you’ll have that much.

Every grower tells me they get sometimes 60% accuracy to 90% accuracy, but I’m like ‘What if I told you that this season you will get 90% and next season will be 92% because we’re going to be constantly improving. That’s the other aspect of AI and machine learning.

So in short, we try to treat plants as algorithms and we have to understand this black box and what the factors should be there. And we have a lot of humans in the loop and there’s a sequence of AI machine learning processes that are heavily driven on computer vision, but that becomes raw data to the forecasting model.

AFN: What sets hexafarms apart?

DA: One unique difference between hexafarms and others out there is that we want to have one massive model, kind of like what current AI models like ChatGPT, etc. do, and the idea is that the model would be deep and rich enough to understand the peculiarities of each farm and then tune to it.

As one example, we trained the model on two or three strawberry cultivars, and right now we have about 16 strawberry cultivars in our system. And the performance is actually pretty good. To run a new cultivar for us takes about a week to get to human-level performance or better.

Adding one more crop is not a big deal. Of course, when we go from strawberries or tomatoes to raspberries, it’s a bit different because the dependents are different, but we’re actually working on that right now as we go into this new financing round.

AFN: Why indoor farming?

DA: We try to stick with CEA and the reason for that is that these operations have to really improve their profit margins and they offer the best playground for our technology. It’s more concentrated and you can get more returns and have less variability, and that’s why a tool like ours is easy for indoor growers.

But there’s nothing fundamentally stopping us from going outdoors, and as a matter of fact, we have done that.

We also serve foil tunnels and are planning to go out into normal fields once the AI models can understand crops a bit better and it’s easier to get clean data. We recently had a camera out in the field and we saw sheep count in the data.

We have customers in Germany, Netherlands, Austria and Switzerland. You can see cultural differences across the greenhouses.

Some are very elegant, some won’t let us actually step into the greenhouse — we have to let them install the devices because they don’t trust anyone. In others there’s a tendency to produce as much as possible so they have things like moving table tops.

When I was fundraising an investor pointed out the fragmented market and asked how we were going to cater to it. I love software. I can write one that can be used by almost anyone, and I love this fragmentation; it has really shaped our tool.

AFN: Some areas of indoor agriculture have gotten a bad reputation in the last couple of years. What are your thoughts on indoor agriculture as a whole?

DA: Using indoor farms for growing food profitably is 100% possible. But some investors just did not read their history books, and companies were using systems that didn’t even have simple things like CO2 sensors in the farms.

I can make a prediction about the greenhouse market and CEA in general: it’s just going to grow more and more. Climate change is real, and so is the increased demand for high quality and healthy produce. Every single one of our greenhouse customers is already profitable, but we want to make them even more efficient and at the same time, give this head start to new operations just starting out regardless of whether they are starting a greenhouse in the Netherlands or in Dubai.