The secret to Pinduoduo‘s gargantuan growth since it launched just six years ago?

It has always been in the right place at the right time, Xinyi Lim tells AFN.

“We were founded in 2015, when a lot of people thought China’s e-commerce landscape was more or less settled with Alibaba and JD,” says Lim, who is Pinduoduo’s executive director for sustainability and agricultural impact.

“But we set out to do something different. We realised that agrifood was this blue ocean space. It was not well served by the incumbents, but everybody buys fresh produce – and the Chinese buyer in particular buys with high frequency and high volume. So we decided, ‘let’s sell something everybody needs.'”

“I think we picked the right spot, and started at right time,” she adds.

Back in 2015, China was just beginning to experience the take-off of mobile internet, with smart wallets like Alipay becoming more common. At the same time, ‘everything app’ WeChat was becoming ubiquitous; while third-party logistics had also reached an inflection point, improving fulfillment times and bringing down costs.

“It was as if all the digital roads and highways were being paved, and we could take advantage of that. It was very opportune,” Lim says.

“If you’re [an e-commerce player] dealing with items that are lower ticket prices — like apples or potatoes — suddenly it actually made business sense.”

Of course, it wasn’t all just good luck. To make the most of serendipity, Pinduoduo had to execute well on both business and technology fronts.

Headquartered in Shanghai and operating across China, Pinduoduo started out as a farmer-to-consumer business. Initially, it purchased produce from growers before selling it on to shoppers. Later it transitioned to a pure marketplace model, hosting third-party vendors and connecting them directly to consumers.

Pinduoduo was one of the pioneers of the community group-buying model, which allows individual consumers to team up in-app and collectively buy goods in bulk from sellers. This enables customers to get better bargains on produce, while farmers are able to create efficiencies by selling and shipping larger loads.

“The observation of the founding team was that e-commerce was lacking that social element you have in offline settings – like going window shopping with your friends, where you can ask for their opinion. Sometimes you actually do want your friends to be part of your purchase, to take their suggestions or follow their lead,” Lim explains.

At first, Pinduoduo users had to form buying ‘teams’ of 10 people minimum. The company also decided to focus on just a few select items of produce — typically, whatever happened to be in season, or what its farmer partners had a glut of and needed to sell quickly — in order to bring prices and delivery times down as much as possible.

“[Users] were very willing to share news of these deals with their friends, and that drove rapid growth at an early stage,” Lim says.

This had a virtuous circle effect at the supply end of the platform, too.

“It helped us aggregate a large number of orders in a short period of time, so we could become a meaningful buyer of fresh produce. At one point we were influencing the market prices of fresh produce because we were such large buyers,” Lim says.

“Because we have this focus on being more social, on getting users first, having that word-of-mouth recognition gave farmers confidence [that] this is a platform they should be transacting with.”

“Word spreads among farmers [too]. They may be in a village where others are selling the same thing, so if we are buying and they run out, they might ask their neighbor farmer [if] they want to sell to us.”

Overtaking Alibaba

Pinduoduo’s user-first, social approach has certainly offered up some impressive results.

Recently, the company — which floated on the Nasdaq in a $1.6 billion IPO in July 2018 — issued its Q1 2021 report. Revenue was at $22.2 billion ($3.38 billion) for the quarter, an increase of over 3x on Q1 2020.

Much of that growth can be pinned on Duo Duo Maicai, the company’s express grocery delivery service which launched in August 2020 and is already live in over 300 cities. It offers a smaller selection than the company’s main app, but with faster fulfillment and a focus on fresh produce.

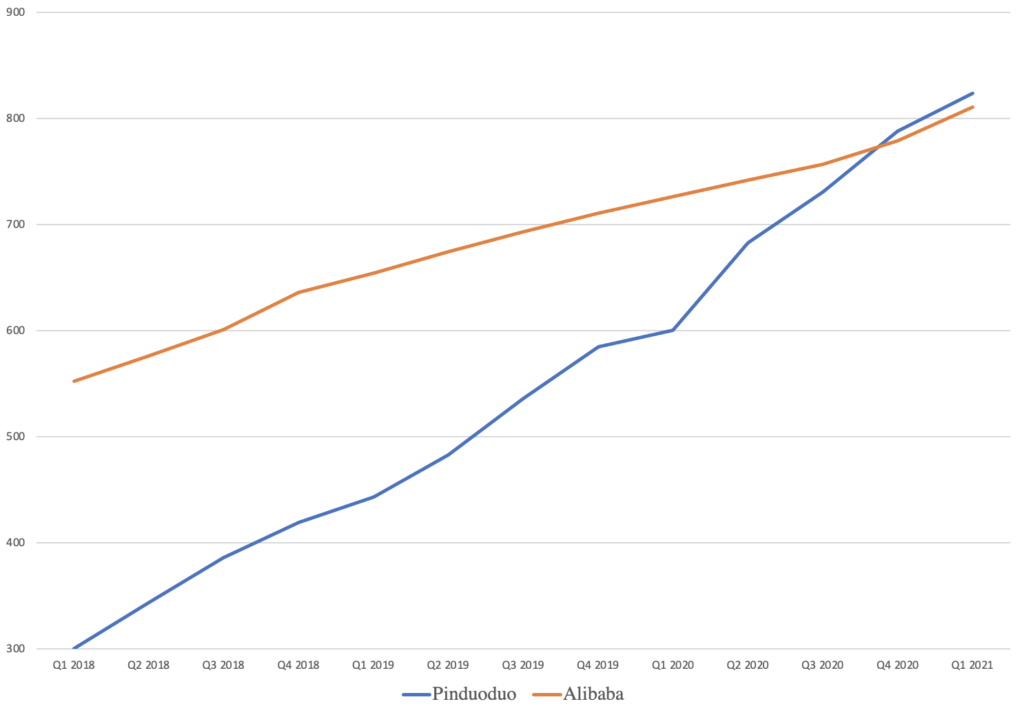

Overall, Pinduoduo’s monthly active users were up 49% year-on-year, reaching 725 million; while ‘annual active buyers’ — users who make at least one purchase on the platform — for the 12 months ending March this year hit 824 million, up 31%.

It’s this last stat which Pinduoduo — which now calls itself “the largest agriculture platform in China” — seems keenest to broadcast, since it puts it ahead of its closest domestic rival Alibaba for the second consecutive quarter. That makes it the country’s most widely-used e-commerce site (Alibaba recently reported 811 million active buyers for the same period.)

Natalie Wu, managing director at equity research firm Haitong International Research, said that Pinduoduo “registered a strong quarter of revenue growth ahead of expectations, with its Duo Duo [Maicai] business driving user engagement.”

“The strong growth in annual active users and monthly active users show that they are on the right track in terms of driving user engagement,” she told the South China Morning Post.

“A lot is just us focusing on unmet needs in the market. [As to] why we have been able to beat Alibaba’s numbers, we always think our key difference is that we serve users, while Alibaba serves merchants,” Lim suggests.

“When we first started, we only sold ag produce because we noticed it was the only thing large platforms weren’t doing. Alibaba and JD were pitching the whole idea of consumption upgrade; if they can push higher value items, that’s also helping their revenues – and that’s why there was such a wide open space for us in fresh produce.”

It hasn’t all been plain sailing for Pinduoduo, however.

Like Alibaba, it has recently fallen under the microscope of Chinese regulators.

Unlike Alibaba, it is yet to turn a profit.

Moreover, Pinduoduo’s share price dropped after its Q1 announcement, despite the rosy revenue and user numbers. According to analyst Mitchell Kim, who publishes on equity insights platform Smartkarma, it was the numbers which weren’t published that may explain why some investors decided to sell.

“For the first time, Pinduoduo [didn’t] disclose its trailing 12 months’ GMV [gross merchandise volume] in Q1 2021,” he writes.

“GMV growth is decelerating rapidly. Companies typically stop reporting GMV on a quarterly basis when the growth falls to below 30%. This typically signals that monetization becomes more important.”

“The gross profit margin dropped sequentially while the operating loss ratio expanded […] When revenue growth starts to slow, the path to profit must be shown clearly,” he adds.

Pinduoduo chairman and CEO Chen Lei, who took over the reins from founder Colin Huang in March, had acknowledged at the time of the company’s FY 2020 results that it “can, and should, do more.”

Turning to tech

In a statement following the Q1 results, Chen said that Pinduoduo’s “growing scale” gives it “greater capacity as well as responsibility to live up to [its] mission to ‘benefit all.'”

“As we work towards our goal of becoming the world’s largest agriculture and grocery platform, we must also seize the golden opportunity to transform and modernize the agrifood system,” he said.

One way in which it can do that, as Chen alluded to in his statement, is by focusing more closely on technological innovation.

It’d be a return to first principles for Pinduoduo, which got where it is today by finding a niche amid the growth of the mobile internet in China during the tail end of the last decade.

This time round, the company will be looking at tech that can bring greater efficiencies to logistics, such as robotics, self-driving vehicles, and “a more flexible […] agriculture-focused infrastructure” built around data on delivery timings, route optimization, and warehouse locations, Chen said.

“We are quite knowledgeable and familiar with user demand patterns, and doing simulations to focus likely demand and follow that upstream. And when we marry that with what we’re doing on grocery side, where there are physical assets we have to coordinate, [we] can shorten delivery times and reduce food loss and waste,” Lim explains.

Food waste mitigation is just one element of Pinduoduo’s broader drive to contribute towards a more sustainable supply chain that’s able to withstand shocks brought on by population growth, climate change, and — as we have seen over the past couple of years — pandemics.

“We’re thinking about how we can make entire food system more resilient, from how food is produced, to how it’s transported, to how it’s consumed,” Lim says.

Pinduoduo’s founder and former CEO, Colin Huang, feels the same.

Just as Pinduoduo released its FY 2020 results in March, marking the first time it had overtaken Alibaba in active users, Huang stepped down as chairman and director to “pursue research in the food and life sciences,” with Chen taking his place (Chen had already replaced him as CEO in July 2020.)

In a letter to employees, Huang said that Pinduoduo’s runaway success had been driven by its improvements in downstream distribution and supply chain efficiency; but, to continue to thrive going forward, it would need to shift its focus to upstream innovation, in areas such as foodtech and biotech.

“Improved efficiency in distribution and sales still does not fundamentally add value to agricultural products, nor inherently improve our health significantly. What can we do if we were to take a step further and go beyond efficiency improvements?”

Alternative proteins and functional foods are among the areas that Pinduoduo is looking at from an innovation perspective; Lim says that Pinduoduo is “actively investing” in the alt-protein space, without giving further details.

However, enhancing consumer confidence in such products is just as important a task as actually investing in their development, she adds.

“As we start selling these products, we want to give consumers assurance. We can fund research [into the health and safety of these new products] but, given our size given and our role, there’s also more we can do with the results.”

To this end, Pinduoduo just announced a research collaboration with the Singapore Institute of Food & Biotechnology Innovation (SIFBI), which is part of the city-state’s national R&D agency A*STAR.

With the Chinese company’s backing, SIFBI is carrying out a study into the nutritional impact of replacing traditional animal proteins with plant-based analogs. The research partners claim it’s the first time that researchers will focus specifically on the human health implications of novel, plant-based meat replacements, rather than plant-based diets more generally.

It’s Pinduoduo’s second tie-up with SIFBI, alongside an existing project to co-develop a cheaper, more portable test for pesticide residues on produce.

“It’s important for us to have the groundwork done — either through research collaborations like with SIFBI, or by investing to learn through startups, or by holding startup competitions — so we can sell these [alt-protein] products with a clear conscience,” Lim says.

“At the same time, we bring value because we are the largest ag platform — there are a lot data points being generated, a lot of insight into consumer preferences — and we can get timely feedback to producers [to help them] move faster and get these products to be more affordable for consumers.”

“Having come from the mobile, app-based e-commerce sector, [we’re] aware that a common challenge is how to make things more affordable and accessible to the masses. This is a focus for us: We want to get started early, to have a say in and an influence on the development of these technologies. By investing in these areas through research and through startups, we can ensure that our consumers can eat well and our farmers can earn better.”

Comment? News tip? Story idea? Email me at [email protected] or find me on LinkedIn and Twitter