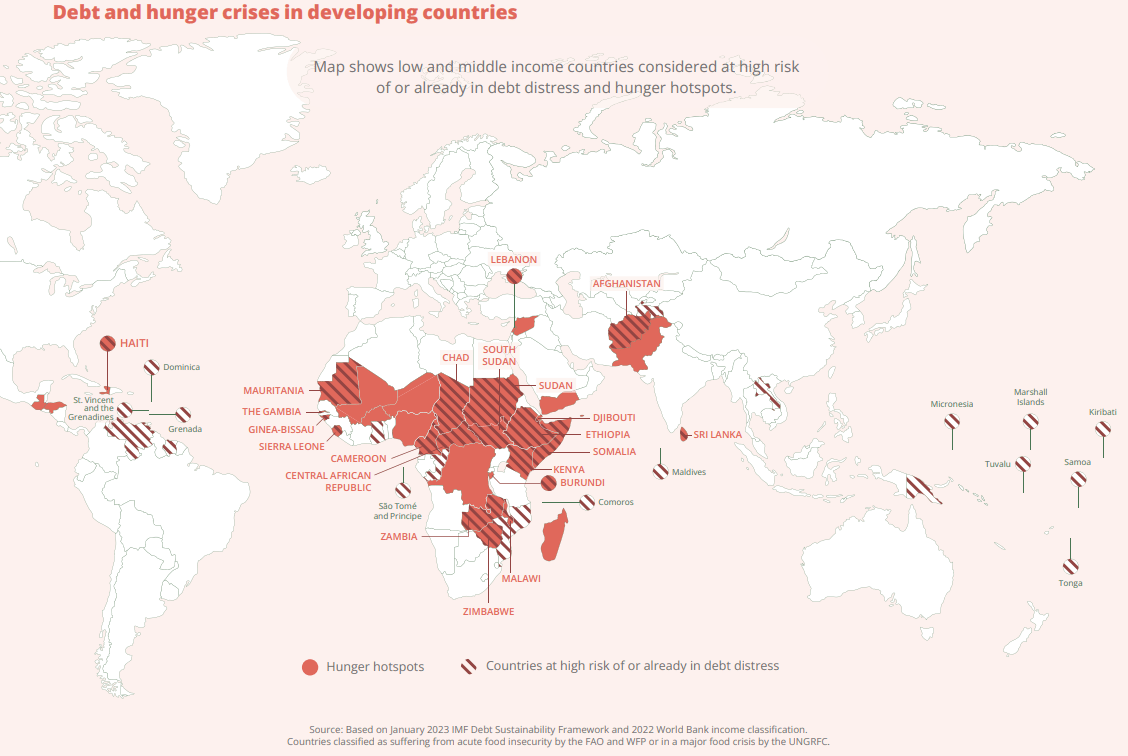

- Global public debt, the highest seen in 60 years, is causing a spike in food insecurity, according to a new report. This is especially true for low-income countries where around 60% are facing a debt crisis and debt servicing costs have gone up due to the depreciation of their currencies against the dollar.

- Recent global happenings — the Russia-Ukraine war, supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic and rising energy costs — have driven up food prices so much so that food import bills have increased by nearly $5 billion in some of the poorest countries.

- The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (iPES Food) argues in the report that our unsustainable and inequitable global food systems are in fact deepening the debt crises, exposing a debt and hunger loop that’s forcing countries to choose between feeding people and repaying debt.

How are food systems feeding the global debt crisis?

The report identifies four key elements of our food systems that exacerbate global debt.

- Import and dollar dependencies. Countries are often dependent on staple food imports, usually grains, at the cost of boosting their food production systems. This is especially true in Africa, which has reportedly seen a tripling of its food import bills. But this overreliance on imports led to shortages when the Russia-Ukraine war prompted a surge in food prices.

According to the report, “As prices spiked over the past year, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa spent an additional $4.8 billion on food imports, despite a decline in total volumes, while the world’s net food-importing developing countries faced a crippling $21.7 billion in additional costs for only slightly higher import volumes.”

2. Extractive financial flows. The report claims governments outsourcing ag financing to the private sector and other corporates negatively impacted the development of their ag industries. In the case of Brazil in 2016, the government cut funding to anti-hunger schemes, even though they had demonstrable success. The result: nearly 60% of households faced some sort of food insecurity.

3. Boom-bust cycles and corporate consolidation. Boom-bust cycles, often characterized by price volatility, do not favor developing countries. Farmers, in response to unexpected commodity price drops, have to take on massive debt to invest in costly machinery and inputs.

“For the world’s poorest rural communities, many of whom are net food buyers and have little access to state support, there is no upside to global price volatility,” the report details.

On the other hand, consolidated ag corporates are the only winners in a boom-bust event as they can control food systems and hike their prices, according to the report. To make this more vivid, the nine top fertilizer companies are reportedly on track to see a fourfold increase from 2020’s profits to $57 billion in 2022.

At the same time, they get bailouts during downturns and have windows to make profits that are re-invested into crucial parts of food systems, reads the report.

4. Climate change. The world has reportedly lost the last seven years of its agricultural productivity growth due to climate change. The report claims low-income countries don’t have sufficient contingency funds to deal with climate change effects, due to their high debt servicing costs. This is in the wake of less than 3% of public financing being allocated to climate altogether.

Is there a way forward?

The report poses some solutions to reduce the impact of food systems on increasing global debt. These include:

- Providing debt relief and development finance of the right scale

- Repairing food system injustices and returning resources to the global south

- Democratizing financial and food systems governance

Find more about these solutions in the report HERE.