This year will likely be the worst year of the commodity price downturn for US row crop farmers as many enter their third year of negative net incomes, according to Kenneth S. Zuckerberg, senior research analyst at Rabobank Food & Agriculture.

There has been some positivity in the market in recent days with some rallying in soft commodity prices. All eyes are also on the weather in the coming weeks as many growers wait for optimum weather conditions before planting, which increases the risk of planting late and therefore negatively impacting yields.

But for Rabobank, an oversupply of grain and agricultural land in production has put a ceiling on commodity prices for the next five years unless there are a series of shocks such as droughts, Zuckerberg told AgFunderNews.

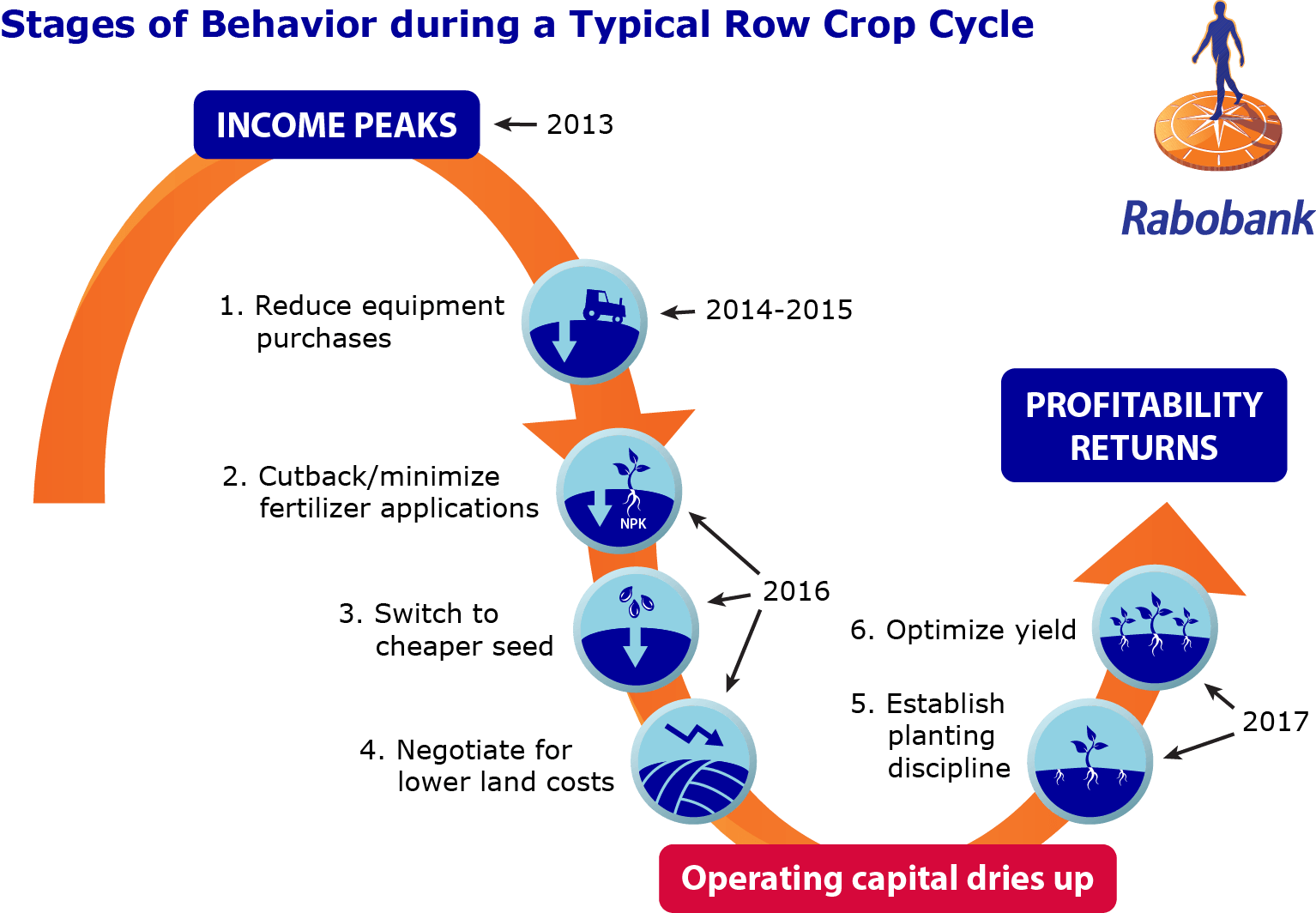

In the recent report “Ch-ch-ch-changes: US row crops are near the point of stabilization“, Zuckerberg and his colleague Sterling Liddell illustrate the scenario with the below infographic.

The commodity price downturn started in 2013 after a period of all-time highs, began impacting machinery and equipment purchases in 2014 and 2015, and this year will see farmers pullback on fertilizer applications, switch to cheaper seed, and negotiate for lower land costs.

Zuckerberg also believes that along with a stabilization in crop prices, farm incomes will stabilize around long-term break-even levels for five years. This means the situation will not improve as quickly as in other commodity cycles. “This is based on Rabobank’s view that commodity prices will not improve much over the intermediate term,” Zuckerberg told AgFunderNews.

So what does this mean for agtech startups?

“I would assume that negative farm incomes are having a huge impact on the adoption rate for many start-ups,” said Scott Henry of LongView Farms, a farm operations company, in Nevada, Iowa. “They argue, and are somewhat right, that this is where their value is — saving producers time and money by having better, accessible information to make decisions. But the pool of dollars that operations have to spend is smaller.”

And this means that, more than ever, agtech startups need to show farmers and their service providers what return-on-investment they will get before they adopt agtech.

“It relates to the efficiency of the invested dollar for an operator,” Henry added. “We haven’t been sold on the value offered by several of these start-ups to justify the annual fee. Had their product been more developed in 2012, then I think we would’ve potentially overlooked some of the initial shock of the fee and pursued things further. Unfortunately, many were just in their infancy at that stage of the game and therefore were not able to capitalize on the economic fortunes of the ag industry.”

Kris Tom from family-run Tom Farms in Leesburg, Indiana was a bit more positive about the situation.

“I do see agtech adoption slowing down a bit, but as the average age of the farmer grows, and the younger generation comes in, adoption of technology will always increase.”

Zuckerberg sees light at the end of the tunnel, but not before more pain for the sector. In around 2017 to 2018, he thinks farm consolidation will occur, and the natural synergies and benefits of these unions will keep new agtech purchases off the table for a short while.

In 2019, however, to drive productivity gains, these new large, consolidated farms will seek agtech again, he argues.

“Adoption of agtech to drive productivity gains will continue to be delayed until the emerging new technologies can prove to be value-added, and this delay increases the risk of down rounds for startups over the next few years,” he said. “It could also lead to consolidation among agtech startups with the stronger companies looking to bolster their offerings with the technology of those that are less successful.”

It’s worth noting that the above refers to agtech companies targeting row crop farmers; those in the specialty crop or livestock sectors have different drivers to adoption and crop prices. The number of acres under management in broad acre farming – around 300 million acres — and therefore the overall value of this segment of the agriculture market – around $155 billion – is far larger than the specialty food crops segment. But berries, tree crops, and specialty vegetables are still worth at least $35 billion and are more valuable on a per acre basis than broadacre farms, making even moderately-sized operations more cash rich and able to adopt new technology. Labor shortages across much of the specialty segment, particularly at organic farms, makes the need for agtech solutions arguably greater too.

What do you think? Will the current downturn highlight the importance of agtech for farmers, or keep adoption at bay? Get in touch on [email protected].