Rachel Hor is the chief operating officer of CarbonTerra, a Saskatchewan, Canada-based company focused on soil health dedicated to developing a carbon-neutral agricultural ecosystem in the region.

The views expressed in this guest commentary are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of AgFunderNews.

The Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry in Canada is currently engaged in an extensive examination of soil health across the nation. This initiative forms part of their efforts to conduct a fresh study on Canadian soil health. I had the privilege of participating in Senate hearings earlier this year, where I gained unique insights while interacting with Senators and other participants.

It’s been 39 years since the last and only such report was compiled in 1984. The findings of that report underscored the significant issue of soil degradation throughout Canada while emphasizing that the nation stood to lose its agricultural productivity without urgent intervention.

However, the past four decades have seen dramatic changes, especially in technology. Agriculture, like every other industry, has gained from this, and Canada’s agricultural exports have surged to make the industry more competitive globally.

In the province of Saskatchewan, we recognized the importance of soil health decades ago when in the 1980s we grappled with critical soil-related challenges. We have since made remarkable strides, driven by technological advancements, heightened sustainability awareness, and a resolute commitment to preserving soil health. Today, Saskatchewan is recognized as the breadbasket of Canada, thanks to its fertile soil that significantly contributes to the national and global food supply. According to Statistics Canada, the province accounts for a staggering accounts for 43.1% of total cropland in Canada.

This revival could be largely credited to the widespread adoption of zero-till practices across the majority of our farmlands. Techniques such as cover-cropping, rotational grazing, and intercropping have also played pivotal roles in revolutionizing the agricultural landscape, resulting in improved soil conditions, increased crop yields, and a more sustainable future for agriculture.

Advantages of zero-till

Zero-till, also known as no-till or direct seeding, is a conservation-oriented farming practice that entails planting crops without conventional plowing or extensive soil disturbance.

As of 2016, 93% of cropland acres in Saskatchewan was under conservation tillage. Given the province’s flat terrain and periodic strong winds, this practice acts as a protective barrier against soil erosion, preserving precious topsoil and its vital nutrients. It also contributes to enhanced water infiltration, reduced surface runoff, and improved moisture retention—all critical for maintaining healthy soil and fostering optimal crop growth.

Moreover, zero-till reduces the need for extensive machinery and labor associated with plowing, thereby curbing operational costs and greenhouse gas emissions.

Shifting to no-till seeding also led to a reduction in land allocated to summerfallow, a practice involving leaving land unplanted to rebuild soil moisture while controlling weeds in semi-arid regions of the Prairie provinces, notes Statistics Canada.

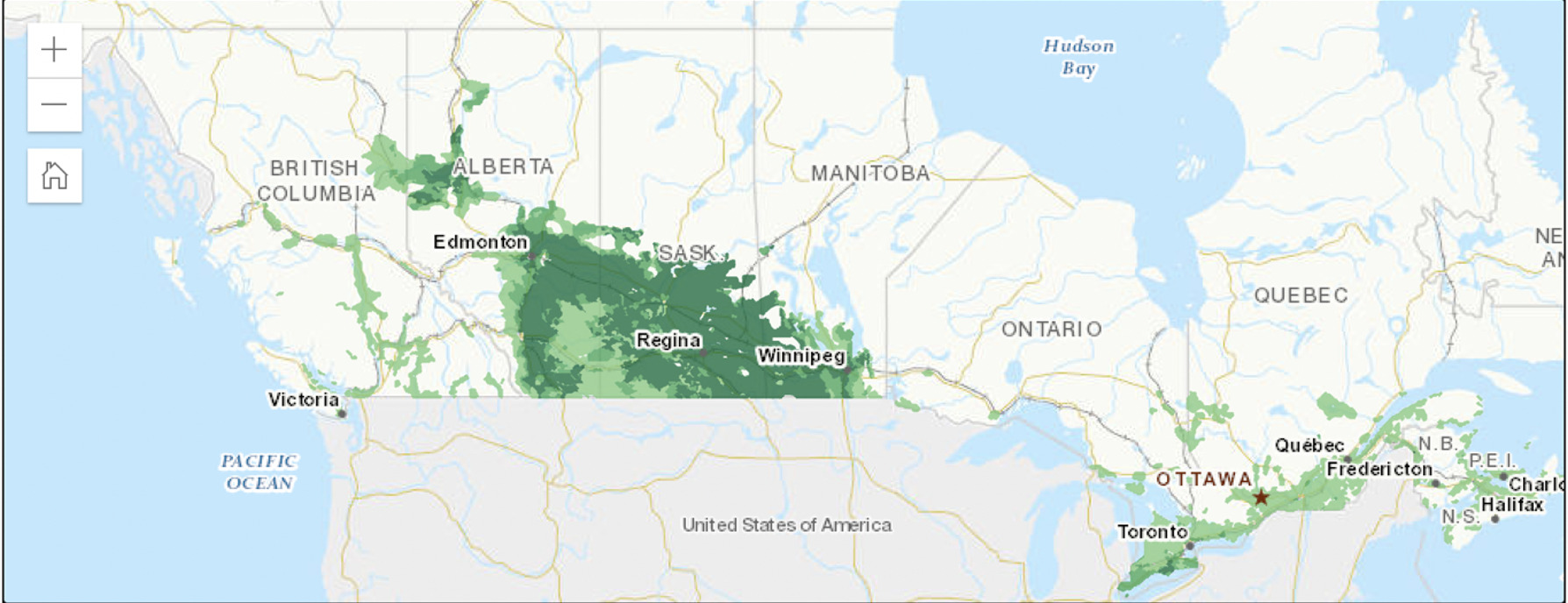

The map below shows the cumulative changes in organic carbon, directly resulting from reduced tillage and summerfallow:

Zero-till practices play a pivotal role in mitigating climate change by enhancing carbon sequestration in the soil. The Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute highlights that the adoption of “no-till methodology has had a dramatic impact on carbon losses in western Canada, moving the provinces from a net loss of carbon to a net gain position since 1981.”

Furthermore, a recent study from the Council of Canadian Academies observed that between 1990 and 2020, there was a remarkable expansion of 18 million hectares of land under conservation tillage in the Canadian Prairies, resulting in a substantial increase in the introduction of carbon into the soils (primarily Saskatchewan). It’s worth noting that this study also highlights the existence of notable uncertainties regarding the consequences of reduced or no-till practices in eastern Canada.

A comprehensive long-term analysis shows that in western Canada, no-till practices resulted in an average annual increase of 0.14 tonnes of carbon per hectare over 23 years, while eastern Canada observed a relatively lower average annual increase of only 0.06 tonnes of carbon per hectare over 18 years.

A study by Soil Society of America estimates that no-till farming has the potential to sequester up to 0.3 tonnes of carbon per acre per year.

On Saskatchewan farmlands, carbon sequestration due to zero till farming is in the range of 0.3 to 0.65 tonnes per acre per year, according to another study carried out by GHG Registry, an organization dedicated to establishing scientific criteria for carbon sequestration projects, along with the experts affiliated with CarbonTerra.

Giving farmers their due

The Saskatchewan soil-health renaissance is prime example of agricultural innovation, a practice now embraced by other provinces in Canada and many other countries across the world.

However, it is unfortunate that the pioneers of this practice are not receiving the recognition they deserve.

In other geographies, farmers are incentivized to adopt no-till practices, and some even earn money through the carbon offset market. For instance, Quebec farmers were incentivized to switch to no-till, an initiative that saw a 69% rise in the adoption of the program between 2009-2013. Similarly, the Chicago Climate Exchange compensates land managers with approximately $2 to $3 per acre for adopting practices like conservation tillage for carbon sequestration.

In contrast, Saskatchewan farmers do not receive benefits for their decades-long commitment to sustainable practices, such as tax breaks or incentives. They are even excluded from the growing carbon offset market due to federal regulations implemented in 2022. The Greenhouse Gas Offset Credit System excludes those who have already embraced no-till farming from engaging in the carbon market. The regulations stipulate that only projects that commenced after January 1, 2017, and can demonstrate verifiable and lasting reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, are eligible for federal GHG credits.

This is grossly unfair for a province which had 93% of cropland acres already under conservation tillage (zero-till/minimum till) by 2016. It is almost penalizing early adopters for being early adopters.

Immense environment benefits

Saskatchewan’s farmers stored 12.8 million metric tonnes of carbon in their soil in 2020, primarily due to their extensive use of zero-till practices, surpassing every other province in Canada. This is equal to the environmental benefit of taking around 2.78 million cars off the roads for a year. The data is part of the national greenhouse gas inventory, an annual submission prepared by the federal government for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) each year.

And while both provincial and federal governments have been claiming credit for the adoption of sustainable practices that have resulted in substantial carbon sequestration in farmlands, the farmers —the true architects of this transformation—are receiving no benefits.

Senator Sharon Burey, a member of the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, acknowledged in a recent article that providing financial incentives to farmers is key:

“The committee has heard from young, medium-sized and Indigenous farmers who were unable to access funding and resources dedicated to the adoption of BMPs, which is often a costly investment. We must ensure these practices make better economic sense than their less sustainable counterparts, and that the programs that promote them remain agile and deliver adequate support.”

Last year, Saskatchewan’s Lieutenant Governor, Russ Mirasty, mentioned creation of a Saskatchewan-based carbon offset credit program in his throne speech. The program was designed to potentially offer incentives to farmers who engage in practices aimed at sequestering or reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Unfortunately, there has been no progress so far.

Evolving carbon market and policies

Traditionally, carbon credit programs tend to prioritize new projects and initiatives due to the specialized and ever-changing nature of the market. However, the scenario in Canadian Prairies, especially in Saskatchewan, presents a unique challenge as it largely overlooks the significant contributions made by some of the earliest adopters who have been actively sequestering carbon for an extended period through practices like zero till farming, and have also set precedents for others across the world.

These early adopters find themselves at a disadvantage primarily due to the technical criteria of “additionality” and “permanence.”

One major argument often raised against them is the difficulty of proving additionality since they have already incorporated these practices into their farming operations. To satisfy the additionality requirement, they would need to demonstrate that their carbon sequestration efforts go beyond standard industry practices. Given that their adoption of zero-till farming may have occurred many years ago, it becomes challenging to showcase a clear departure from their previous methods.

Another concern relates to the issue of permanence, since the carbon stored in the soil through zero-tillage practices can potentially be released back into the atmosphere if tilling practices are reintroduced. This presents a significant hurdle in demonstrating the lasting nature of carbon sequestration, aligning with the criteria established by carbon credit programs.

However, long-term studies such as the Prairie Soil Carbon Balance Project demonstrate an incremental positive carbon change in carbon levels, even up to three decades after transitioning to no-till or continuous cropping practices. Moreover, these observed carbon gains extend deeper into the soil profile than initially expected, underscoring the substantial and enduring impact of such sustainable farming approaches.

It’s worth highlighting here that the effective sequestration of soil carbon relies on continuous management, as alterations in land management practices can lead to the release of carbon into the atmosphere.

Policy is the issue

Agriculture assumes a significant role in the context of global greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to approximately 10% of Canada’s overall emissions. However, it also holds immense potential as a carbon sink, actively retaining carbon rather than emitting it into the atmosphere.

For instance, AAFC’s Environmental Sustainability of Canadian Agriculture report highlights improvements in soil quality and conditions nationwide between 1981 and 2011, attributable to enhanced land management practices and a shift towards more sustainable agricultural methods.

What strengthens this case further is AAFC’s Strategic Plan for Science which acknowledges the absence of a clear net-zero pathway for agriculture that doesn’t compromise Canada’s food production or the long-term viability of the agricultural sector. The plan emphasizes the necessity for substantial research mobilization to fully harness AAFC’s extensive scientific capacity and uncover new practices and technologies.

Saskatchewan’s remarkable journey towards enhancing soil health serves as a testament to the potential of agricultural innovation.

The current approach of completely overlooking the early adopters is flawed as it not only ignores the aspect of emission reductions, but also the substantial investments of time, finances, and resources required for the implementation and maintenance of such farming practices.

The failure to acknowledge early adopters can result in adverse consequences, including:

- Discouragement of sustainable practices, resulting in decreased adoption and reduced carbon sequestration

- Incentives for unsustainable practices, increasing emissions and damaging soil health

- Creation of inequities in the agricultural sector, favoring larger producers and hindering the transition to sustainability

- Impediment to climate change mitigation progress, as no-till farming plays a crucial role in reducing emissions

Promoting broader adoption of sustainable practices not only enhances Canada’s competitiveness in the global market but also yields environmental benefits while fostering a more profitable agricultural sector.