Liberation Labs — a startup aiming to address capacity bottlenecks in biomanufacturing — has secured $30 million in equipment financing to support its first commercial-scale precision fermentation facility in the US.

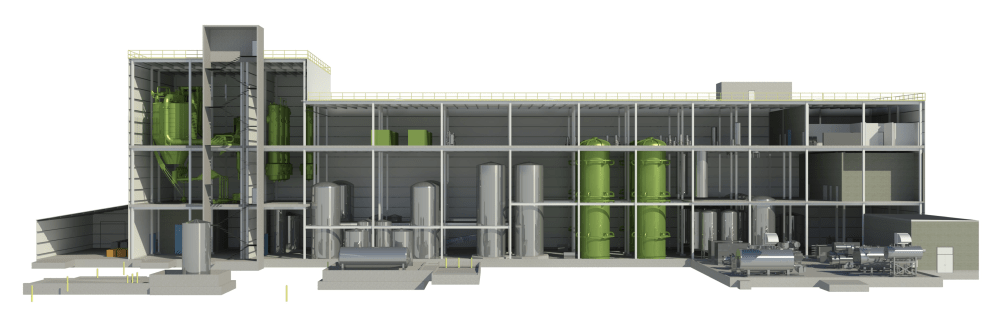

The purpose-built site in Richmond, Indiana, will have 600,000 liters of capacity and is set to become operational by the end of 2024.

Designed to cater to a range of customers from “better funded precision fermentation startups” to established ingredients companies and CPG brands, the facility will also have dedicated downstream processing capabilities, said co-founder and CEO Mark Warner.

“This new financing, combined with our $20 million seed raise last year, allows us to not only secure all the needed equipment, but also to continue investing in our team to move the overall project forward at speed,” added Warner, who aims to build a global network of biomanufacturing facilities.

He told AFN: “Long term we’re looking at six geographies worldwide. In each one, we expect to build initially a 600,000 liter launch facility and ultimately a 4 million liter commercial facility.”

Why it matters

Over the past few years, millions of dollars have flowed to precision fermentation startups using synthetic biology to program sugar-eating microbes to produce everything from whey protein to vanillin.

The problem, according to a recent report from Synonym Bio, is that the infrastructure to get these companies from pilot to commercial scale simply isn’t available. Aging biopharma contract manufacturing capacity is unsuited for food-grade projects, while investors have proved unwilling to fund new facilities for startups with no experience of industrial scale fermentation.

“The majority of users [of capacitor.bio, a tool helping firms find fermentation capacity] are looking for commercial-scale or demo-scale facilities that simply don’t exist to meet current, let alone future, demand,” said the report.

‘The average contract manufacturing facility people are using today is 50 years old’

Enter Liberation Labs, which aims to address the bottleneck, Warner told AFN.

“The average contract manufacturing facility people are using today is 50 years old and it was built for pharmaceuticals. It sounds great to retrofit an old facility, but it’s just not as efficient as a fit-for-purpose facility. Our facility in Richmond will be the first fit-for-purpose precision fermentation food protein manufacturing facility in the world, to my knowledge.”

Asked about trying to raise money in the current climate, he said, “We need $115 million for the Richmond project. The equipment accounts for roughly a third of that and most is already on order. For the rest of the money, we’re looking at additional equity options, a Series A raise, but we’re also looking at additional debt options beyond the equipment financing. We’ll need to do something by late this year on one of those or a combination of both.”

Overall, he claimed, the process of trying to raise capital has “been better than I expected… Three years ago, if I pitched a bunch of VCs on a quasi-infrastructure play, that was something they didn’t really want to fund. But since forming with our initial investors [such as Agronomics and CPT Capital ], who are heavily invested into these [new precision fermentation] companies, we convinced them that we needed to move forward with speed.

“We started the project on equity [funding], but I’m very confident the reason we were able to get the equipment financing [ie. debt] is that we had moved the project so far along. We now have the things banks and traditional financing are used to seeing.”

“It is noteworthy that, while there are a large number of exciting novel food ventures based in the US, almost all commercial production is being done outside the US, entirely due to a lack of available domestic fermentation capacity. The most common locations are in Mexico, Italy, Czech Republic, India, Germany, Spain, and Slovakia. This is especially ironic as the only consumer market with regulatory approval for many of these novel proteins is the US.” Mark Warner, CEO, Liberation Labs

Sugar, energy, labor

Building Liberation Labs’ first facility in Richmond, Indiana, made sense for several reasons, he said. “Our criteria are access to sugar [feedstock for microbes], energy, and labor, and Richmond had all three.

“It’s within an hour and a half of three corn wet mills that make industrial dextrose; it’s close to three metropolitan areas (Indianapolis, Cincinnati, and Dayton); and it has ample electric power, half of it is locally generated from solar.”

Meanwhile, 150,000 liter fermenters are large enough to deliver efficiencies, but small enough to be fabricated off site, said Warner.

The economics of precision fermentation

Asked about the commercial viability of some of the ingredients that startups are trying to make via precision fermentation, he said: “Something like lactoferrin, which has a high dollar value, is certainly attractive, but once you get to the 50 to 100 bucks a kilo range, that’s where it starts to get difficult. Really anything that currently sells for less than 50 bucks is a challenge, although it also depends on how much you use in a given application.

“As you really get into what I would consider bulk products, there’s going to need to be additional development on the process to reach viability.”

Blue Horizon: “Pretty much everyone we run into is facing some difficulty in terms of scale-up”

While the US is currently the global leader in biomanufacturing and biotechnology, this lead cannot be taken for granted, argued precision fermentation specialist Conagen in a recent letter to the Biden Administration to help inform its National Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Initiative: “The lack of sufficient US manufacturing capacity is causing a backlog of promising innovations that cannot be commercialized.”

As AFN has recently highlighted in articles about Remilk and Superbrewed Food, however, investors have proved reluctant to provide the capital to fund large-scale fermentation facilities for new products until they see some market validation.

Nate Crosser, principal at Blue Horizon, which has backed a series of companies in the precision fermentation space including Geltor, Change Foods, and The EVERY Co, told AFN that capacity is a “major issue for the entire bioeconomy.

“Pretty much everyone we run into is facing some difficulty in terms of scale-up. Some of that is inevitable. If you’re commercializing a novel bio product with no existing market, there’s a significant risk there that neither co-manufacturers nor bankers are necessarily comfortable financing.”