Editor’s note: Scott Nichols is the founder and principal of Food’s Future. Its mission is to accelerate the expansion of responsible aquaculture.

Scott works to create a food future filled with a plentiful supply of healthful and delicious fish by assisting businesses that create aquaculture feeds, raise fish, and expand markets for farmed fish. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of AFN.

A farm on the water does the same thing as a farm on the land. It grows what we eat. The techniques differ but the endpoint is the same: dinner.

Terrestrial agriculture produces more of everything—animals and vegetables—than does aquaculture (farming in the water). On land, the world’s farmers raise about 335 million tonnes of meat and the big three—cows, pigs and birds—account for 94% of that.

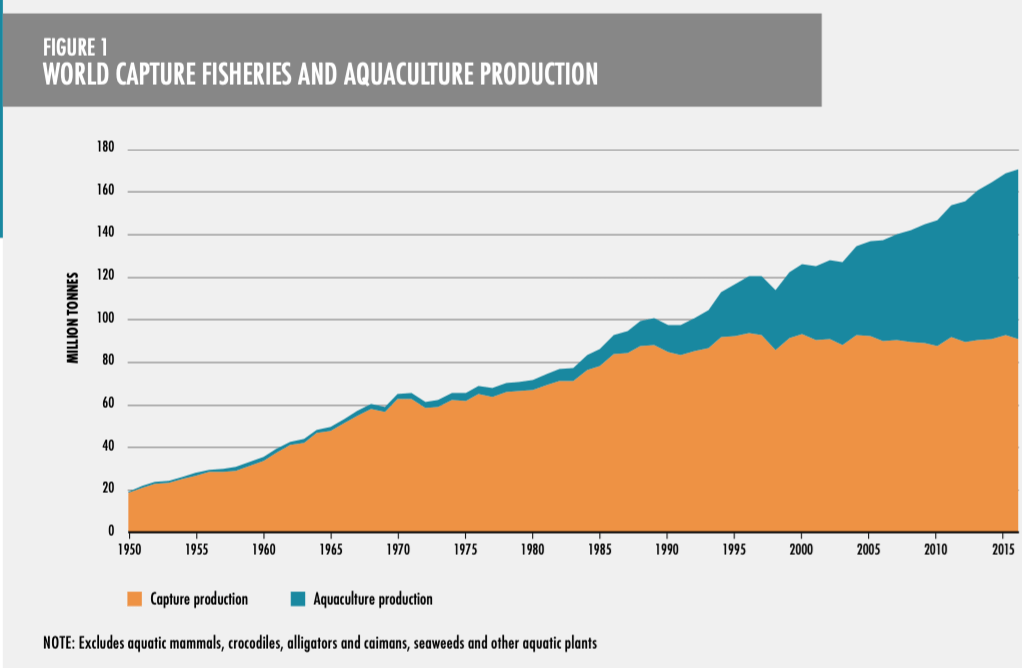

Aquaculture’s total is 80 million tonnes — an additional 90 million tonnes comes from fishing. What’s most striking about aquaculture is that even with production volumes so much smaller than the terrestrial big three, fish farming provides vastly greater diversity. In contrast to terrestrial animals, 40 different fish comprise 86% of aquaculture’s harvest. Aquaculture production isn’t evenly distributed throughout the world; the lion’s share of farm-raised fish, about 90%, come from Asia. China’s production alone is two-thirds of that.

How do you farm in the ocean?

It turns out there are lots of ways. That stands to reason; as you’d imagine, a mussel and a salmon call for different husbandry practices.

To begin, seafood farming has a whole category of animals not raised on land—animals we don’t need to feed. The bivalve mollusks— oysters, mussels, clams and scallops—are filter feeders. Every day as tides go by, they filter out the free-floating bacteria, single-cell algae and animals that make up the plankton. As they filter and clean the water, they absorb the nutrients they need to grow. For the price of a wire mesh box (clams and oysters) or a string attached to a buoy (mussels and scallops) we get ecosystem services and delectable food. It’s not quite something for nothing, but it surely is a lot for a little.

Fed- aquaculture is varied. Seafood grows in on-land water bodies near the shore, and far off-shore. Shrimp, tilapia and catfish grow in lakes, rivers and ponds. Such farms range from relatively unsophisticated small mom-and-pop operations to multiple hectare-sized farms controlled by complex systems. Their markets are equally diverse and range from local subsistence consumers up to large international retailers.

A bit farther from shore are ocean net pens. Finfish such as seabream, seabass, salmon, cobia and others grow in enclosed nets suspended from the ocean surface. Led by salmon producers – largely in Norway, the UK, Canada and the Faroe Islands – these farms develop and deploy the highest technology practices used in fish farming. Virtually all of the fish from these farms go into international markets.

Fish that grow to harvest size in ocean pens begin their lives in on-shore hatcheries. These are, usually, indoor facilities that contain batteries of tanks. Their sizes range from egg containers of a few liters to those with diameters up to 10 meters. As the fish grow, they move to ever larger tanks until they achieve the proper size for transfer to the ocean.

Perhaps the most interesting of hatcheries is for salmon. All salmon have distinct fresh and saltwater phases in their life cycle. Just like wild salmon, farm-raised salmon start life in freshwater.

In a hatchery, eggs collected from brood fish are fertilized and hatch about 60 days later. When they’re nine to 12 months old, hatchery salmon begin a process similar to that experienced by young salmon in rivers. Altering lights to mimic springtime daylength launches young fish into a complete physiological rewiring that prepares them to live their adult lives in saltwater. Then, equipped with their new metabolism, the young salmon, now called smolts, go to the ocean for the adult phase of their lives where they live for some 20’ish months until they reach harvest size.

Two emerging practices

An extension to the hatchery concept is to raise fish all the way to maturity in on-land tanks. The approach isn’t brand new; it has had success with both tilapia and barramundi. For salmon, however, the technology is relatively new and it’s now beginning to capture the fancy of many investors.

A new and potentially exciting third type of aquaculture is farming in deep offshore waters. Fish grow in spherical pods attached to a tender boat. In a first test, fish grew faster, required less food and had lower mortality rates compared to those grown in near-shore pens. Though it too is a nascent technology, open water farming offers enticing hope for both agronomic and environmental benefits.

Vegetables

For vegetable crops, land-based production dwarfs what comes out of the water. Seaweed is aquaculture’s most produced vegetable. It’s production is roughly equal to garlic whereas the world’s largest land crop, maize, is over 35 times larger. For the time being, aquaculture is an animal-focused business.

The most important difference?

A 2018 study by the US Department of Agriculture using data collected from 1987-2012 found that farm size doubled in 40 of 55 crops examined. Another USDA study found that profit margin increases with the size of the farm. Up to illogical extremes, terrestrial agriculture benefits from scale.

In fish farming, an area’s so-called carrying capacity defines its ability to provide the ecosystem services needed to raise fish. Quantifying an ecosystem’s carrying capacity is difficult; the science is arcane. Qualitatively, however, it’s easy to understand. An environment can only support a certain amount of fish. Exceed that and you degrade the resources you need to raise your crops.

As farming businesses, this makes aquaculture and terrestrial agriculture fundamentally different. Importantly, fish farms are replicable though not scalable; the polar opposite of the drivers on land. This makes intuitive sense when you think about the nature of farms on land and in water.

On the land, farms replace the environment. A drive through the US mid-west slams this point home. Maize and soybeans aren’t interspersed within tall-grass prairies. The prairie is gone—removed and replaced by crops.

By contrast, aquaculture happens within the environment. A fish farm performs best by integrating completely into the environment whilst imposing minimal impact. As a result, large-scale farming isn’t the optimal path.

As we think about how to plan businesses and raise capital to increase food production through fish farming, this is certainly something to keep front of mind.

Where now for fish farms?

Agriculture is the most crucial of human endeavors. Whittled down to its irreducible essence, agriculture has two missions – to provide us with the calories and the nutrition we require to live. Fish admirably provide both. As our food future makes a greater call for high-quality food, aquaculture is poised to play a central role.

Are you working on a technology for the aquaculture industry? We’d like to hear from you! Email [email protected]