From edible coatings and ethylene scavengers to modified atmosphere packaging, irradiation and cold plasma, there are multiple ways to extend the shelf-life of perishables, each with their pros and cons, says RipeLocker, which has a novel approach it claims can double the shelf-life of some high-value crops.

Cofounded by George Lobisser and his son Kyle in 2016, the Seattle-based startup has developed patented, re-usable, portable low-atmosphere chambers it claims can significantly extend the post-harvest life of everything from blueberries, kiwifruit, cherries, and walnuts to roses by creating a near-vacuum or ultra-low oxygen environment.

The approach, which reduces respiration by more than 50% on average, can help growers switch from air freight to ocean freight, reduce losses due to decay and pathogen control, achieve higher grading of fruit (with a higher price tag), and store fruit to enable sales during late season premium price windows, VP sales Julian Lewis (JL), tells AgFunderNews (AFN).

But as with any new technology, he says, there are barriers to uptake if your solution requires users to modify their current approaches: “We’re working with operators that are happy to disrupt and do things differently for better results.”

AFN: What’s the origins story of RipeLocker?

JL: George ran [fresh produce preservation firm] Pace International for a number of years, turned it around and sold it Valent BioSciences [part of Sumitomo] in 2012 [it has since been acquired by AgroFresh]. But he always had this lingering frustration about the poor quality of produce by the time it reaches the consumer. When you get products out of controlled atmosphere storage, the quality can be fantastic, but by the time they get to the retail shelf, you don’t always get the best quality.

So it was a case of how can you make that controlled atmosphere room portable? So he played around with a lot of different technologies and hit upon vacuum storage. This has been used for giant reefer-sized containers that cost tens of millions, but he wanted to create something mobile and economic.

AFN: So how does the technology work?

JL: George’s son, who was a design engineer, worked with his father to design the RipeLocker. It’s been through many iterations, but we now have this chamber where basically, you put fresh produce in it, you pump it down [suck out the air to create a near-vacuum], and you can dynamically control the oxygen and CO2 levels inside.

Any kind of produce is likely to be an aerobic system that consumes oxygen and gives off carbon dioxide, and depending on what the produce is, we’ll very closely maintain that level dynamically, at the point that keeps it aerobic, but only just… and so it’s not quite a vacuum. We maintain the atmosphere at a level that’s tailor made for blueberries or avocados or whatever the produce type is and basically put it to sleep.

The act of doing that slows decay and senescence, although some products respond better than others, particularly blueberries. Recently, we worked with a breeder and brought some berries to an IFPA [International Fresh Produce Association] show that were over 100 days old, and they were in very, very good condition.

We’re very active in blueberries, cherries, flowers, so things like roses from Colombia going to the US. We’re also testing soft fruits such as raspberries and blackberries as well as avocados, mangoes, and pomegranates.

AFN: How does your tech compare to modified atmosphere packaging (MAP)?

JL: No nitrogen is pumped into our system; all we do is pump air in and out. MAP can be a great solution but vacuum storage can offer significant benefits in terms of senescence suppression and ultimately shelf-life. We don’t generally compare the technologies as they both have their own role to play, but as an illustration, for blueberries, MAP bags can typically store them for three to four weeks, while the RipeLocker can store them for eight weeks and in some cases 12+ weeks.

For cherries, MAP bags can typically store them for four weeks, while the RipeLocker has had great results at eight weeks. Finally for whole pomegranates, controlled atmosphere rooms and MAP will store them for one to two months, whereas the RipeLocker can store them for more than four months.

Generally, MAP systems can take between one to two weeks to build up the optimal storage atmosphere as they are a passive system relying on the respiration of the fruit. In fact, the ‘optimal’ conditions may never be fully achieved. The RipeLocker achieves the optimal conditions within hours due to the use of a vacuum pump.

RipeLocker can achieve lower oxygen and/or higher carbon dioxide levels that are optimal for senescence control than passive controlled atmosphere or MAP technologies without inducing fermentation [ie. switching to an anaerobic environment], low-oxygen injury or carbon dioxide damage.

Basically, in a vacuum, or rather an ultra-low oxygen environment, respiration of the fruit is still enabled with very few oxygen molecules in a low-pressure environment, but it also means we can enable much higher carbon dioxide levels which can also control senescence and inhibit ethylene action in some crops [ethylene is a plant hormone that fruit & veg produce naturally as they ripen].

Due to this environment, ethylene biosynthesis can be inhibited, delaying ripening, while fungal pathogens are also suppressed; we have also been able to kill insects with this environment.

AFN: How does RipeLocker compare to tech that applies coatings to produce?

JL: The appeal of the RipeLocker is that it can eliminate some of these coatings, either partially or entirely, depending on the produce.

As for nutrition, we also know that riper fruit is more nutritious and the RipeLocker enables producers to pick riper fruit and store them without the use of chemicals, so there is the potential to deliver more nutritious produce.

AFN: How do you handle temperature fluctuations and humidity?

JL: We are literally pumping air out of the chamber like a vacuum cleaner and any moisture that comes off the fruits is vaporized in the low-pressure environment thus maintaining 100% relative humidity. The other good thing about storage is that there’s zero weight loss or moisture loss from what’s stored because it’s a fully sealed system.

In fact, we have instances of berries actually gaining weight. As for temperature, the control system is constantly monitoring and managing the environment inside the chamber to allow adaptations to unforeseen and undesirable ‘excursions;’ this is something that passive systems cannot do.

AFN: How does the system know if adjustments to the atmosphere are needed?

JL: There are sensors in the control system, and generally one control unit manages 20 chambers.

AFN: What’s the business case for the user?

JL: There are multiple benefits which include the ability to move from air freight to ocean freight, reduce losses in transit, reduce losses due to decay and pathogen control, achieve higher grading of fruit – and therefore the ability to receive higher prices, and also store fruit to enable sales during late season premium price windows.

In the floral industry, we are even enabling growers to store and sell early blooms in peak season. Normally, these early blooms are trashed. RipeLocker has literally turned waste into profits.

The flower industry is super interesting. So almost all the roses in the US come from Colombia or Ecuador. The big peak is Valentine’s Day, so roses aren’t worth much in December, but they’re worth a lot in February.

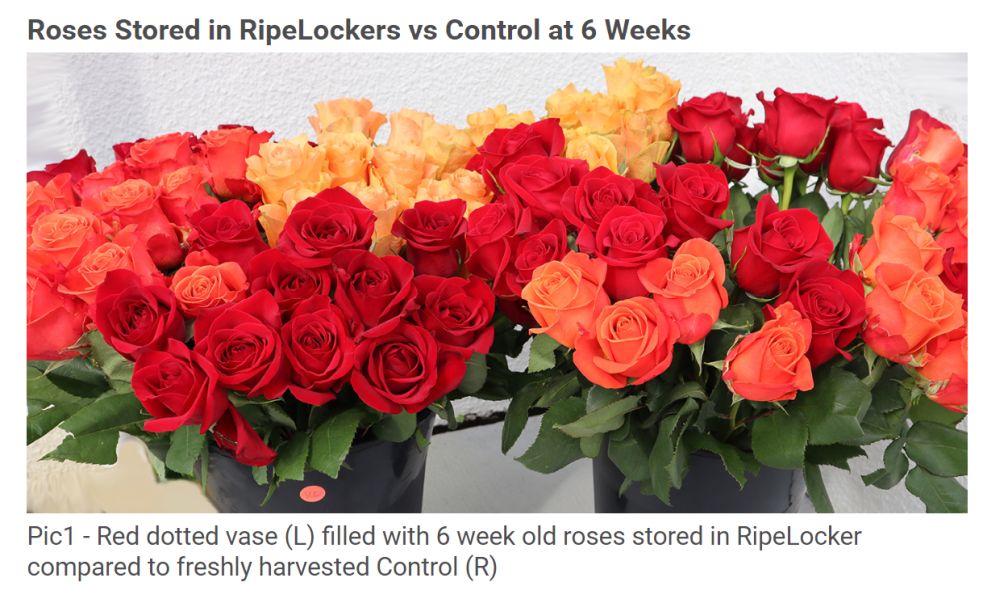

And so any roses that are blooming in December, they cut, it’s called pinching, and they throw them away. They then hope that that rose bush grows again and produces a perfect rose for Valentine’s Day. As we can store roses for six weeks in a RipeLocker, we can store the roses they’re cutting in December, so we can create new inventory that previously was trash.

Our customers are buying RipeLockers to reduce cost or increase revenue, or both.

Take air freight. For [German discount retailer] Lidl in Europe, for example, they are basically saying that in the future, they won’t want to produce that’s air freighted because it’s bad for the environment, so some journeys will become impossible. So if you want to get fresh produce from Latin America to Europe and the product can’t survive an ocean journey, you’re going to lose your access to Lidl, and I’m sure other European retailers will follow suit.

In a RipeLocker, you can literally take the slow boat. So we’re working with growers in South America that cannot get their product from Latin America to China because the ocean journey takes too long for their products. We’re doing the same with companies supplying products from Latin America to Europe.

In other situations, quarantine requirements mean you’ve got to store product in a cold environment for a certain period, which might be too much for your product. In a RipeLocker, it could survive.

AFN: How easy is the system to use?

JL: You take the top off and put your produce inside. If you’re handling something quite robust like an avocado, you can put them in in bulk. If it’s something softer like a blueberry, we have trays and a tray stacker. Then you’ve got a controller connected by hoses to the RipeLockers and you pop the lids on and pump everything down [to create a near-vacuum].

The system is designed to work in stationary storage applications and in transit. We’ve sized the chambers so they can go into a shipping container, so there’s 39 chambers in a container and then the control system will go in there with the chambers. When reefers [refrigerated trucks] go into ships, they have power to drive the chilling of the reefer that can also drive the power of our units. And so we can have very long ocean journeys, let’s say from Latin America to China or to Europe, and this dynamic control continues.

There’s a particularly exciting opportunity in fresh hops. Beer is traditionally brewed with dry hops but with all of these micro-breweries, demand for fresh hops has increased. It’s a little-known fact that 44% of the world’s hops are grown in Washington and Oregon. But fresh hops are only good for 24 hours. We’re able to store fresh hops for 60 days.

AFN: What IP do you have?

JL: We’ve got three patents. One for the engineering design, creating a chamber that can withstand a vacuum with a lot of pressure from the outside. There’s then a patent around the dynamic operating system, so what are the settings for blueberries versus avocados versus pineapple and so on and how do we get dynamically control that?

And then finally we’re collecting data constantly and using that to build predictive analysis so we can start to predict when the fruits will reach optimum ripeness. With some fruits, maybe because the way they were loaded wasn’t optimal, or maybe it was rainy at harvest time, we can go to the customer and say, ‘You need to open chamber # 26 now.’ So we can tell a customer in real time what’s happening to their fruit, and so we’ve got a patent around that.

AFN: What’s the business model?

JL: If you’re going to use RipeLockers year-round, it makes sense to buy them. So for example, we’re working with some of the world’s largest walnut growers, and they’ve stored walnuts for two years in a RipeLocker and they came out in perfect condition.

Similarly, we’re working with tomato growers who only need to hold tomatoes for two weeks, but they are growing year-round, so it makes sense to buy the RipeLockers.

But for blueberry growers in the Pacific Northwest, which have a six-week season, a leasing model makes more sense. So in peak harvest season, the price can be very low, whereas at the end of the season if there’s not many blueberries around, the price goes crazy.

If you can store your blueberries and have them available at the end of the season, you’re going to do very well. But they’re only going to need them for six weeks, so in that instance we will lease the equipment for a fixed fee.

AFN: Is the RipeLocker system designed to work only with produce that’s in the cold chain?

JL: We deliberately didn’t design chilling into the chamber. Typically the RipeLocker goes in a chilled warehouse or chilled shipping container. However, there are some instances where chilling is not required. The vacuum works so well with walnuts, for example, that if they are in a RipeLocker they don’t need to be chilled, so we’re actually saving the industry the cost of chilling.

AFN: What are some of the challenges and barriers to uptake?

JL: We’ve been in commercial use for the last two to three years and this season we’re working extensively with blueberries, fresh hops, and roses. Our commercial progress so far is in stationary storage because it’s the simplest to deploy.

But our original vision was all about a mobile solution, which is logistically more complex [moving the RipeLockers in groups attached to the controller and hoses]. It’s not enormously complex, it’s just an added step, but we don’t hide the fact that using RipeLocker will disrupt your process. So we’re working with operators that are happy to disrupt and do things differently for better results.

I’d say the biggest barrier to progress is the same [for any agtech company seeking to disrupt an existing supply chain]. If you’re talking to established businesses, even those that might have sub optimal aspects of their process, what’s the motivation to change? So part of my role as the business development guy is to find not only big global players, but ones that have that challenger disruptive mindset.

AFN: How have you funded the company?

JL: We’ve funded it thus far through angel investors, basically industry figures who are ag players themselves, and we aim to seek further funding and extend our investor network in the near future.

AFN: What progress have you made to date?

JL: We are currently working with one of the world’s largest growers of berries. We have trials underway in multiple global geographies with multiple commodities. As a result, we hope to make an exciting partnership announcement in the coming weeks.

Another partner is The Queen’s Flowers, one of the largest US importers of fresh roses. The company recently completed a very successful Valentine’s Day campaign using mass storage of roses in RipeLockers in Miami to ensure they could build inventory and offer their customer superior vase life. We will begin our Mother’s Day campaign with them in early April.

We have also agreed an extensive blueberry storage campaign for this summer with multiple Pacific Northwest growers including close partner, Oasis Farms.

Sponsored

Sponsored post: The innovator’s dilemma: why agbioscience innovation must focus on the farmer first