Dutch startup VanderSat has come out of stealth with a satellite data analysis service for the agriculture sector after receiving €1.34 million ($1.6m) in grant funding from the European Commission (EC) late last year.

VanderSat, which joins a growing number of remote sensing startups targeting the agriculture sector, is taking a different approach to others, namely in its use of microwave sensors and data instead of imagery to glean insights about and for the industry.

By collecting data from a range of different satellites operated by organizations across the globe, VanderSat measures soil moisture and soil temperature on a daily basis and has now built up a database going back 16 years.

Using these microwave data, VanderSat is able to alleviate one of the main pain points associated with satellite-derived imagery data: cloud cover.

“The great advantage of going further down the electromagnetic spectrum towards microwave is that you get information about the subsurface of the earth, which is not limited by cloud cover because it’s not in the visual range,” says Richard de Jeu, founder and chief technology officer of VanderSat.

The EC’s Horizon 2020 programme awarded VanderSat the grant in a water for agriculture initiative focused on yielding soil moisture information from satellites. The grant is part of Horizon 2020’s small and medium-sized enterprises instrument, which has around €1.6 billion ($1.9 billion) available between 2018 and 2020 and has funded around $100 million worth of projects so far.

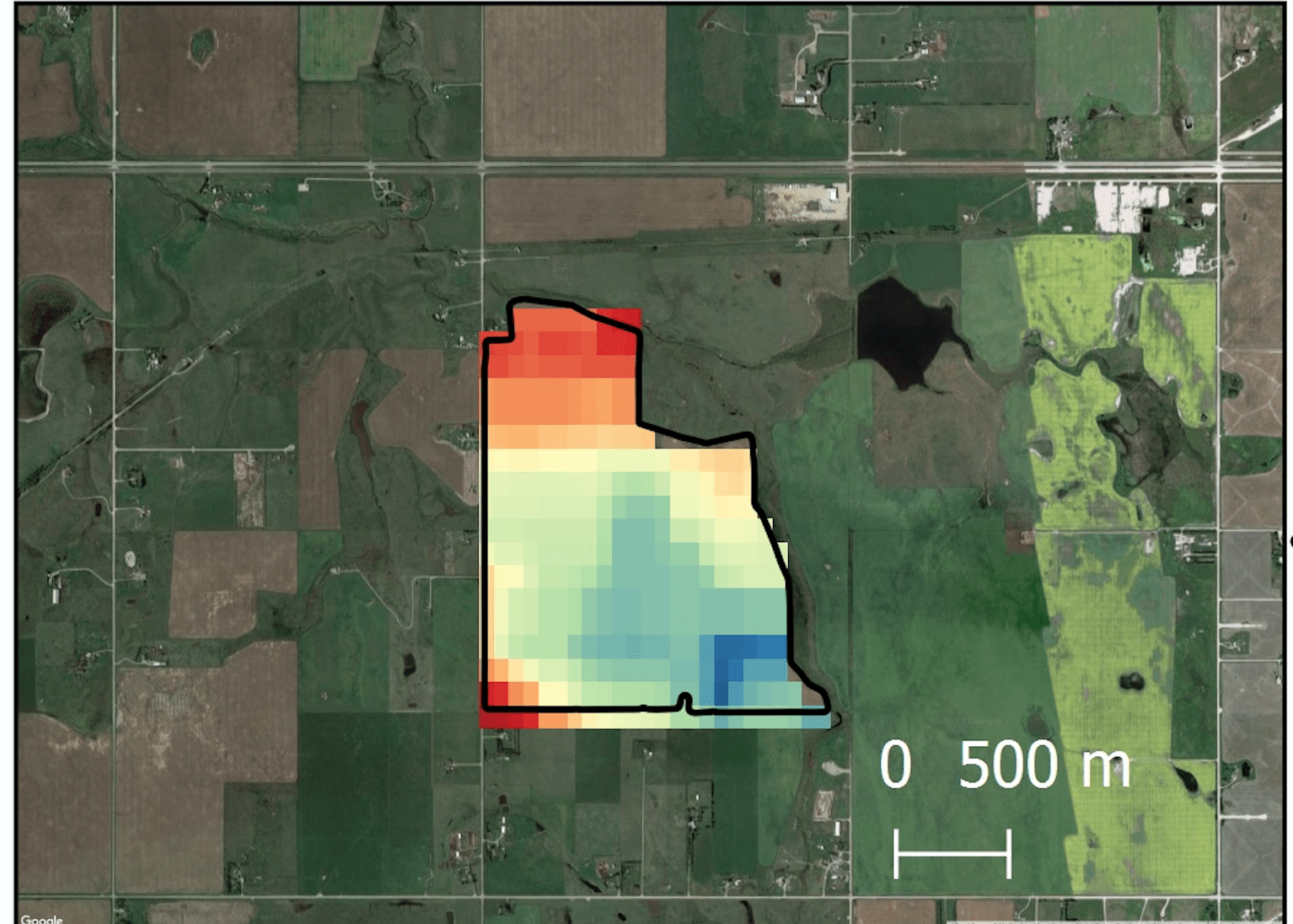

VanderSat collects data from the NASA satellite SMAP, the Sentinel Constellation, and SMOS satellite of the European Space Agency and from the GCOM-W platform of the Japanese space agency JAXA. They all capture slightly different spectra, which the startup weaves together to produce high-resolution data of 100mx100m — competitors often don’t get much further than 25kmx25km according to de Jeu.

This process for stitching the data together to give clients a daily, high-resolution stream, and 16-year historical record, is currently patent pending, according to Menno van der Marel, investor and CEO of the business.

“The combination of high resolution, no cloud cover issues, and a historical archive, makes our offering very interesting for many kinds of clients,” said van der Marel, who invested in the company and joined as CEO a year ago from the cybersecurity space. “What we’ve found with our beta programs over the last few months is that clients don’t believe our data are that good and then after two to six months, they find out how much better they are than ground sensors in terms of accuracy, scale, and timeframe.”

VanderSat is now officially launching its soil moisture and temperature data service after conducting trials on its beta service last year with a range of different clients including insurers, agriculture companies, and governments.

It will likely continue to target large organizations with its bespoke data service that aims to provide them with data streams to help solve specific problems.

“We have a training program that we start our service with our clients, to share with them the applicability of our data and how they might use our data streams to match their problems. Then together we come up with a bespoke service to give them that data in a format that fits with their own software and internal models,” said de Jeu. “We focus on the bigger companies because they have the knowledge on the end-user side and the scale, and we have the expertise on data gathering, processing, and analysis,” added de Jeu.

Agriculture companies might be interested to link VanderSat’s data with their disease models to help farmers decide when the best time to spray is, or with their irrigation planning software systems. Insurance companies are launching new parametric crop insurance based on the data, and water authorities are using the service for water management.

“If there’s a drought, we can actually look at it relative to the previous 15 years and give our clients context and perspective,” said de Jeu. “And with this history, they can train their own models to come up with better solutions.”

The idea for the startup came from de Jeu while he was an associate professor at VU University of Amsterdam, studying the use of satellites to measure soil moisture for climate projects. His time at the university followed two years as a research scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, US.

“I couldn’t understand why only scientists were using these data for research and not the rest of the world in more commercial applications,” he told AgFunderNews.

Why aren’t other satellite data providers using microwave data to avoid the issue of cloud cover? “The microwave community is very small so they’re probably not aware of the potential. Plus the data is not easy to handle; you really need a lot of expertise to convert these complicated signals into something useful,” says de Jeu.

Sixty percent of the R&D team have PhDs which van der Marel says makes VanderSat the biggest group of experts in the field. “It’s a very new and narrow area with a big impact,” he added.

While many entrepreneurs may not have heard about microwave sensing from space, there are a quite a few in orbit right now that each cover the globe over two days, which enables VanderSat to combine them to get daily data. The startup would love there to be more satellites with these sensors on them, however, and de Jeu is trying to convince satellite operators to launch more.

VanderSat is in touch with other satellite data providers such as Planet Labs or some of the smaller startups as the data could be complementary later down the line.

The founders have largely funded VanderSat to-date, excluding around €1 million ($1.2 million) in investment from van der Marl before he joined the company last year, and with revenues set to increase 200% this year (2018), the company does not know whether it will need to raise funding again in the near future, if at all.

photo: VanderSat