Editor’s Note: Drew Fox works for Alpha Capital Research, a US-based investment advisory firm with a long history of investing its own capital and client capital on a discretionary basis in alternative investments, mainly hedge funds and commodities. The firm believes that the unique and evolving characteristics of alternative investments require a customized approach for each client. The company is spearheading the development of milk and other commodity-related programs. Fox can be reached by email here.

Investors are attracted to agriculture by demographics, land scarcity, and technology. Higher prices reflect demand and scarcity, while higher productivity is a result of practice and technology improvements.

A simple and popular way to invest in agriculture is to purchase farmland, and then either manage the farm or lease the land to established operators. The investment return is predicated on the rent or profit generated, plus any change in the valuation of the land on the balance sheet.

Farmland has been seen as an effective way of accessing the compelling supply and demand themes around agriculture. But you don’t have to invest in farmland to benefit from the return dynamics in agriculture. In fact, the return dynamics are very different to those in farmland.

The real opportunity in agriculture lies in capitalizing on the strong supply & demand, and technology-driven themes of the sector.

Is farmland investment the best way to access the opportunity, and if not, is there a better solution?

Can we design an instrument that delivers the real drivers in agriculture, instead of a cashflow and valuation model, and what would this look like?

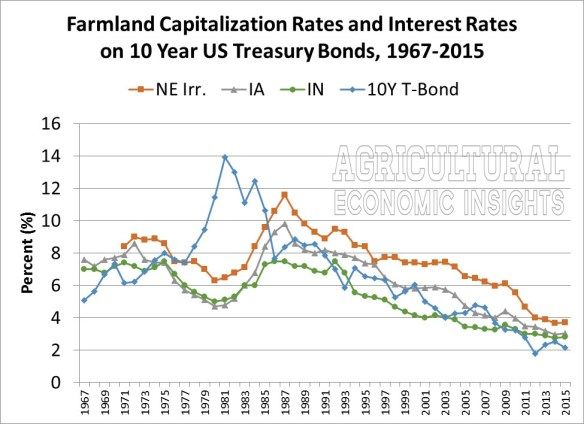

Given today’s current low yield environment, farmland has attracted interest from yield buyers, including pension funds and insurance portfolios. And while these investments have performed well, two issues give investors pause. First, much of the performance is tied up in the mark-to-market where assets are valued by the most recent market price. (Agricultural land has performed very well over the last twenty-five years; Iowa Farmland appreciated by 7.5% year-over-year between 1990 and 2015, according to Iowa State University.) This problem is endemic in the bond proxy world in which we live; investors who clipped 5-7% coupons (interest rates) 10 or 20 years ago are now receiving much smaller cashflows.

And secondly, the search for yield itself means the performance of these assets may now have more to do with the interest rate environment than the particular attributes of agriculture itself. Investors needing to match liabilities will find low (rents) and unpredictable (profit) cashflows impede their deployment of capital to the sector.

So what agricultural attributes should investors be evaluating?

Ultimately, land values are a function of crop price and crop yield. Over long periods of time and for most crops, annual crop prices increase by a little more than 1% per annum, while crop yields increase by a little less than 1% per annum. If you believe farmland values reflect the progression of prices and yields, and you are concerned the rate environment is driving the valuation in the sector, then maybe we should just look at the crop price and crop yield as a source of return. Extracting a return that mimics the evolution of prices and yields allows us to access the driving themes of demography, scarcity, and technology that make agriculture an exciting area for the investor. This can be done.

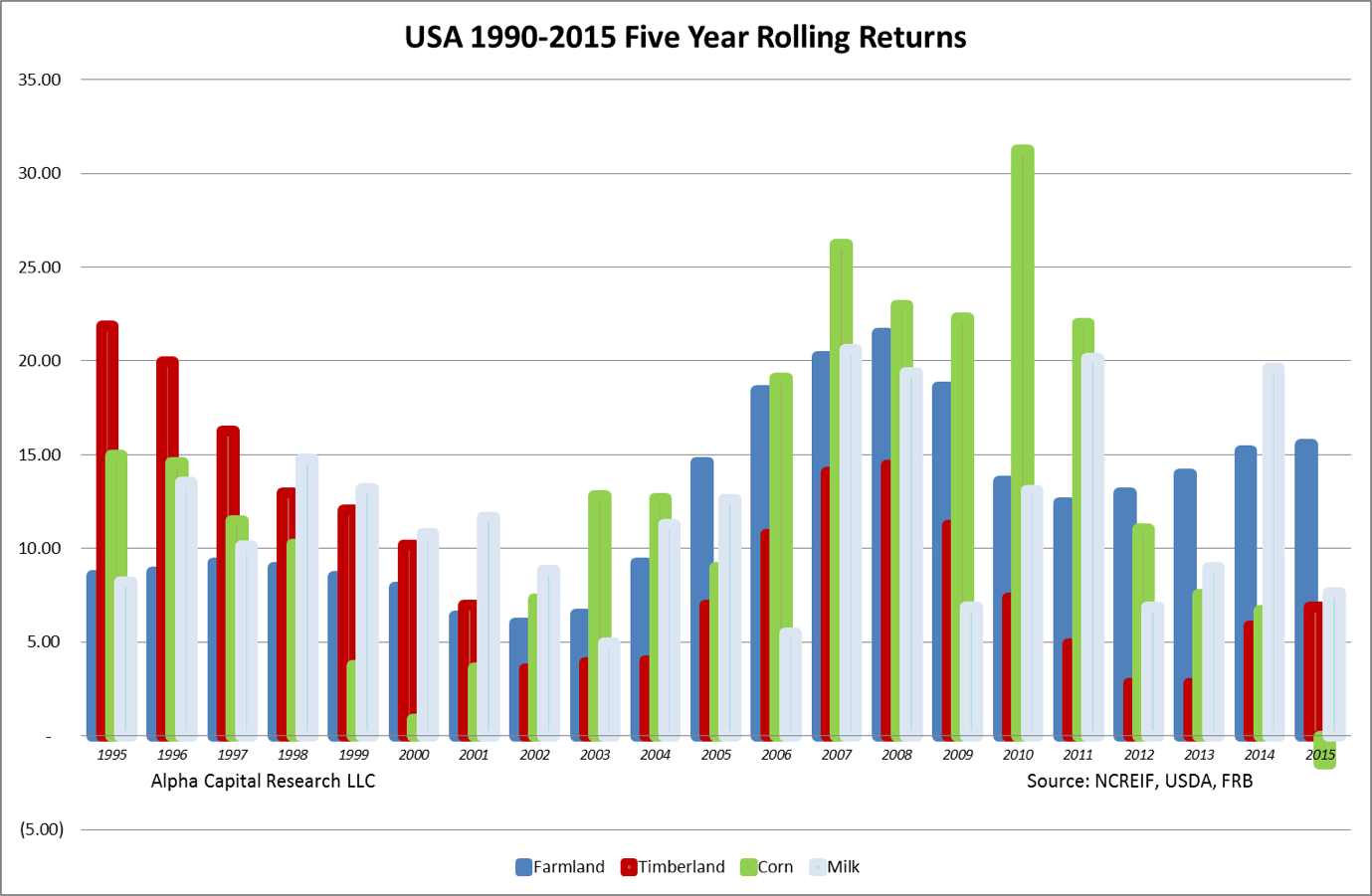

This graph charts the evolution of annualized returns in farmland and timberland. I have added yearly total returns of milk and corn factored by the prevailing interest rate. Using the prevailing interest rate, a crop price and a crop yield, some crops offer annualized returns broadly similar to farmland and timberland, including wheat, corn, and soy. Combining as few as three crops can reduce volatility considerably, and provide some benefits not available to owners of farmland.

For any agricultural producer, the main interaction with finance is borrowing. In the normal course of business, farmers use credit at various points in the production cycle: short-term loans to finance planting, medium term loans or leases to finance farm machinery, and mortgages to finance land purchases.

However, if the loans are factored by agricultural metrics, the lender can receive a stream of principal and interest payments that mirror real time agricultural performance, plus:

- Cash flow certainty, as the income stream is the product of yields, prices and interest rates with definable principal and debt repayment schedules

- Exposure to specific crops, with the potential to hedge or sell forward as you would any other financial instrument

- Freedom from operational risk and execution risk

- A very different return profile when compared to farmland or interest rates

When a farmer uses credit he/she takes the view that money earned from the deployment of new cash will exceed the cost of the loan.

Borrowing is difficult to manage for businesses subject to volatile markets

Matching the interaction between interest rates and commodity markets should be an intrinsic part of an agricultural business. But few and inadequate tools exist to manage this, especially outside the main crops and more advanced economies, to the detriment of the industry as a whole. So offering a farmer a loan tied to agricultural metrics (price and crop yield) makes sense; it matches finance costs to enterprise cashflow and locks in a profit.

An investor contemplating an allocation to agriculture has new challenges with regards to research and due diligence: crop and geographical allocations, entry and exit strategies, underlying social and political issues, sustainability and execution issues. Even for large farmland portfolios, there is a high degree of specific risk. By extending a loan tied to agricultural metrics instead, the investor can buy the exposure to agriculture he or she wants. And she/he can understand the process right from the start.

The trade-off is a long term return for the investor, while the farmer caps his debt repayments as a percentage of enterprise cash flow. The investor is accessing agricultural returns with traditional credit techniques: risk underwriting, credit analysis, risk management and mitigation techniques.

Done correctly, gaining exposure to agriculture by investing in debt might be better than owning the farm.

What do you think? Email [email protected]