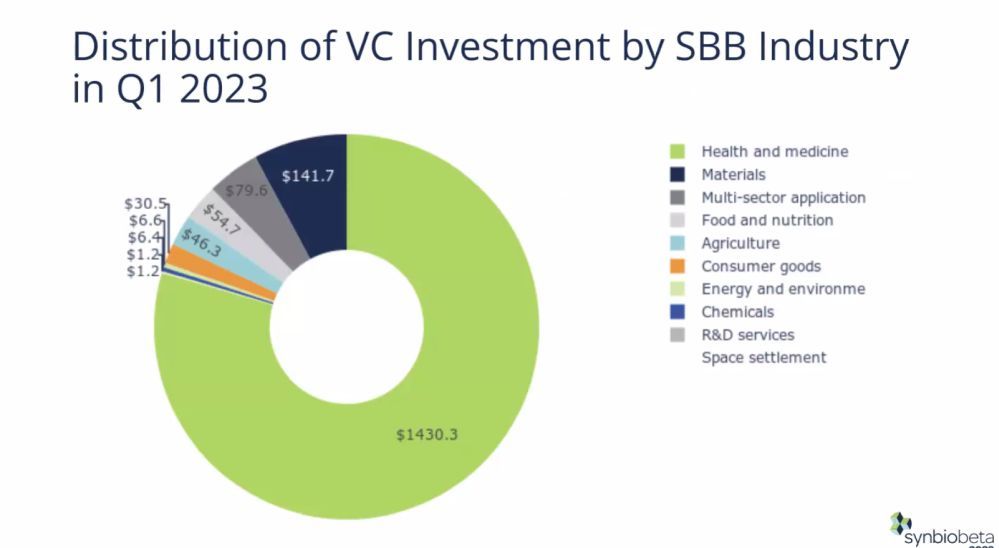

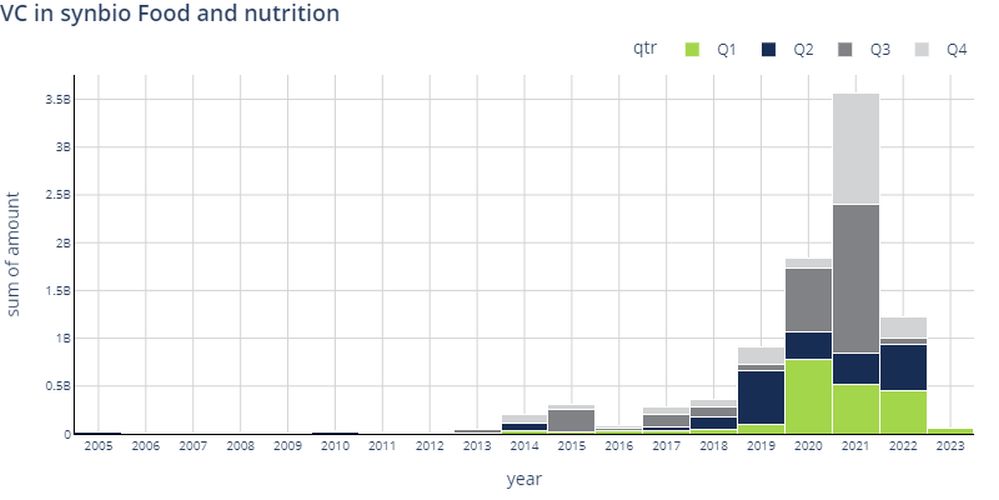

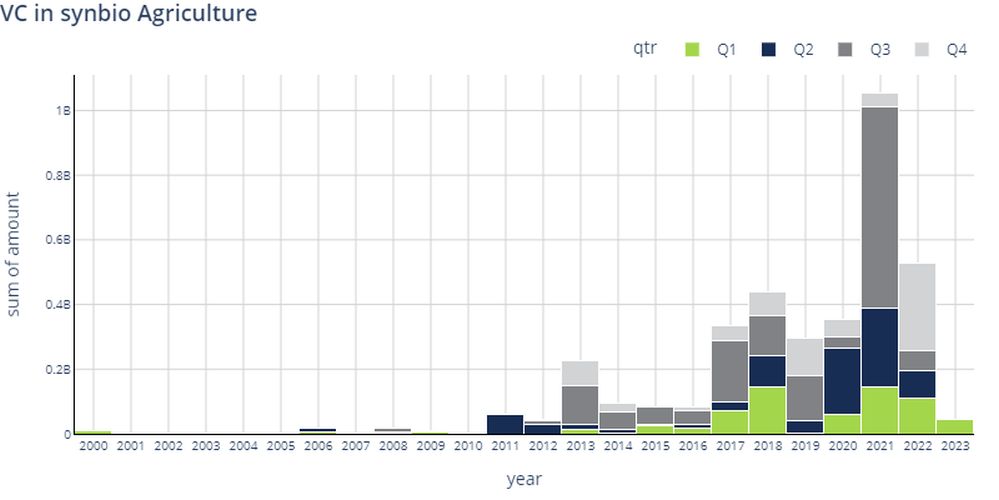

Synthetic biology startups in food & nutrition and agriculture attracted $101 million in the first quarter of 2023, a 73.5% decline versus the same period last year, according to a new report from synthetic biology innovation network SynBioBeta and tech consultancy Futurity Systems.

Of that total, $55 million went to food & nutrition synbio startups and $46 million to agriculture synbio startups.

The drop continues the downward trend experienced across venture capital sectors last year.

In the full year 2022, funding for food & nutrition synbio startups fell 70% year-over-year (YoY) to $1.05 billion, a sharp drop, but still above the $915.4 million raised in 2019. Funding for synbio startups in agriculture dropped 57% YoY to $527.9 million in 2022, an equally big drop, but still above the $294.4 million raised in 2019.

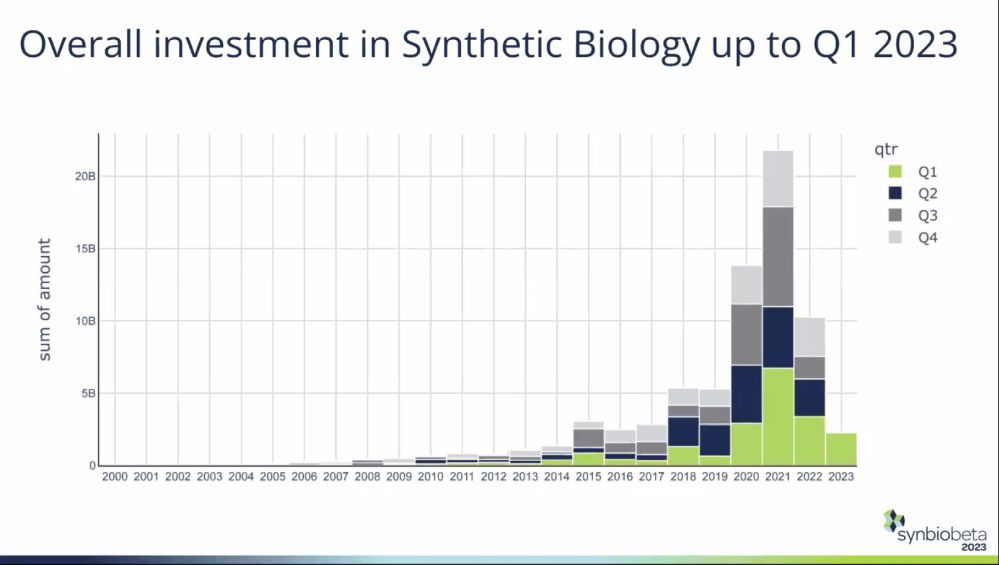

Total investment in synthetic biology startups fell 53% year-on-year to $10.3 billion in 2022. While this decline outpaced the 35% drop in global venture funding in 2022, the 2020/2021 numbers were inflated by the coronavirus pandemic, which prompted a surge of interest in applications of synthetic biology in areas such as vaccines, noted SynBioBeta founder Dr. John Cumbers.

“$10.3 billion is still an incredible amount of money. And if you take out the giant hype cycle in 2020 and 2021, it’s not too shabby to see that amount of money still coming into the industry,” said Cumbers.

As for the potential of synthetic biology to reduce the environmental impact of food production, we’re just scratching the surface, Cumbers told AgFunder News (AFN).

“We’ve got a groundswell of young people who are trained in molecular biology. They’re not scared of GMOs. They’re not scared of technology. But they are scared of the environmental impacts of climate change and disgusted by the dead zones in the oceans caused by agriculture runoff, the pollution we’re creating from coal-fired power plants, and the unsustainability of our consumer culture.”

More transactions, smaller checks

The synthetic biology field combines biology, engineering, and computer science to design and construct new biological systems or modify existing ones by reprogramming the genetic code of organisms from microbes to plants to animal cells. Applications span everything from bananas engineered to resist the devastating Fusarium wilt fungal disease (Elo Life Systems) to bacteria engineered to stave off a hangover (ZBiotics).

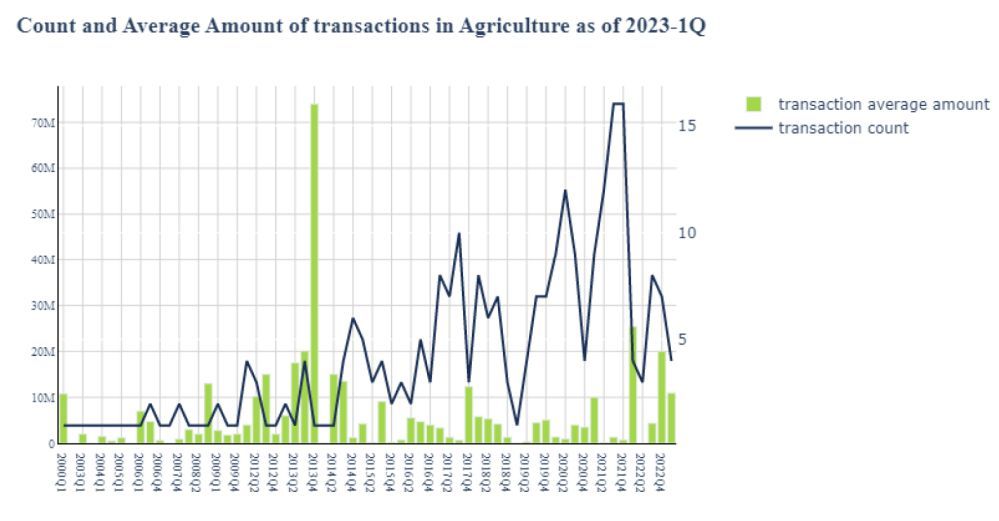

Speaking at a webinar to promote the report ahead of next week’s SynBioBeta conference in Oakland (May 23-25), Futurity cofounder Mark Bünger said: “The ability to design genes and software, to automate lab processes… all of that tool building took a little while. But now we’re seeing a whole flood of new companies come in. Up to around 2012, a small number of companies was getting very, very large amounts of money and now there is a higher number of transactions for smaller amounts of money.”

He added: “In agriculture, synbio startups can be doing anything from soil microbe management to engineering drought-tolerant crops. Agriculture is actually one of the toughest areas… because one, you get to grow things twice a year, maybe three times, and two, it’s an incredibly traditional industry, so the fact that these [synbio startups] have made inroads I think is really remarkable.”

Dr John Cumbers: ‘Biology is not a mature engineering industry… yet’

That said, it’s still early days for startups in the field, Cumbers told AFN.

“The price of reading DNA and writing DNA is falling faster than Moore’s law. But if you look around at mature engineering disciplines like computer engineering or civil engineering or environmental engineering, all of these other disciplines have matured from a hobbyist pursuit to new technology development to now very mature industries with well-understood costs and timelines and things like that.

“Biology is not a mature engineering industry… yet. It doesn’t have well-understood costs and well-understood timelines; that’s what makes it so difficult. Biology isn’t easy to engineer. It’s actually a pain in the ass.”

Food and agriculture applications of synthetic biology

So what are some key examples of food and ag applications of synthetic biology?

If we can re-tool the DNA of bacteria in the soil so plants can more effectively convert nitrogen from the air into food (Pivot Bio, Joyn Bio/Ginkgo), we can reduce the need for synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, said Cumbers.

If we can develop microbial seed coatings that supercharge a plant’s natural ability to store carbon in soil (Loam Bio), we can also help sequester more carbon, he added. If we can engineer microbes to serve as natural fungicides, meanwhile (AgBiome), we can reduce our reliance on petrochemical-based crop protection products.

Similarly, if we can engineer microbes to produce flavors that are found in plants but are routinely synthesized from petrochemicals because we can’t grow enough plants to meet demand (the vast majority of vanillin, for example, is synthetic), we can reduce our reliance on oil, he added.

Dairy and eggs without cows or chickens

Microbes can also be programmed to produce substances made by animals, explained Cumbers. A well-established case study is chymosin, an enzyme used in cheese making that’s now typically made by genetically engineered microbes but was historically sourced from calf stomachs.

Other examples include whey and casein proteins made via microbes rather than cows, and egg proteins made by yeast instead of chickens, production platforms that proponents argue are more sustainable and ethical than industrialized animal agriculture.

Synthetic biology: ‘A movement of entrepreneurs and investors and technologists who want to make biology easier to engineer’

As for synbio techniques, “You’re seeing organisms being engineered from two angles,” said Cumbers. “One is precision fermentation, where I’m going to look at a computer screen, I’m going to drag and drop genes around. I’m going to try different promoters and I’m going to optimize different enzymes.

“And then there’s the more traditional approach using directed evolution on particular regions or particular genes or enzymes.”

But he added: “I don’t view synthetic biology as just as technology around reading, writing and editing DNA. I view it as a movement of entrepreneurs and investors and technologists who want to make biology easier to engineer.

“So I would include cultivated meat in that definition because it’s all engineering work, whether it’s engineering the cells or engineering the whole system that the cells are growing in. So that’s why these companies are welcome in the SynBioBeta community and in the industry, even if they are not reading or writing DNA.”

Microbial workhorses

Looking ahead, he said, for precision fermentation, most companies are still using a handful of ‘workhorse’ microbes such as Pichia pastoris and E. Coli as production platforms. However, “there are several companies now looking at non model organisms and creating transfection systems [for introducing DNA or RNA into microbial cells] and scaling systems for those.

“We’re getting to the stage where you can quickly sequence a genome of a bacterium and you can domesticate new microbes [something being explored by startup Wild Microbes, for example].”

He added: “Let’s say we want to make this particular chemical precursor from fermentation. Instead of going to the usual [production strains of] E. Coli and yeast, you go out into the environment and find microbes that either produce it already or have the right properties for its production.

“You can then bring it into the lab and create this robust chassis organism that you can use for the production of that chosen molecule.”

Ethically-sourced DNA sequences?

Frequently, said Cumbers, synthetic biology relies on finding proteins with specific characteristics. But how do we find those proteins? Chances are, he says, they already exist in nature. Do we then have a responsibility to ensure that natural DNA sequences are “ethically sourced?”

Put another way, he said, “if you find a sequence in the jungles of Borneo, you should be paying some of the royalties back to the people of Borneo.”

One company specializing in this is London-based biotech firm Basecamp Research, said Cumbers.

“They are out there negotiating with Indigenous communities for sequencing rights. They then have a database whereby they can go to companies like Unilever or Procter & Gamble and say, ‘Do you want a new fluffier egg white protein?’ They can then supply you with the sequence for that protein, and ensure that the people in Borneo get a share of the profit.”

- Download the SynBioBeta investment report HERE.

- Find out more about the SynBioBeta conference (May 23-25) and join AgFunder News (AFN) global food tech editor Elaine Watson on Wednesday May 24 to quiz a panel of cultivated meat founders from SCiFi Foods, Meatable, and Orbillion Bio.