Late last year, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania-based Fifth Season abruptly stopped operations at its only vertical farming facility and closed up shop, abruptly and entirely.

While the news surprised many, it wasn’t an isolated event among vertical farming companies. The sector has for some time struggled as sky-high valuations and too much hubris have given way to layoffs, abandoned SPACs and other company closures. As anyone who attended the recent Indoor Ag-Con show in Las Vegas knows, “failure” was an oft-uttered word at the show, so much so that an entire panel was based on it.

Chris Cerveny, formerly a VP at Fifth Season, was on that panel, and had much to share about what vertical farming startups need to bear in mind as they move through this correction phase for the industry.

“We felt like we were doing a lot of things right. Only in retrospect [are there] a lot of lessons that we learned that I’d like to share and hope some of you can learn from kind of the stuff that we experienced,” said Cerveny, who is also a horticulture/CEA consultant via his Bridge City Global advisory firm.

At the show, Cerveny (CC) sat down with AFN to dive deeper into these topics and also discuss specifics about why Fifth Season went under.

[Note: This interview has been edited for length.]

AFN: First off, what happened with Fifth Season?

CC: We had tech investors in Silicon Valley, and they had expectations of how fast things were going to come out. At the same time, everybody was pulling back. So the funding was not readily available, like had previously been, to build a farm of this size and build a national brand.

Also, the burn [in vertical farming] is very high — not just in the utilities and the growing but in the cost of customer acquisition and all the things that you have to do to try to build a national brand. It’s all designed to be profitable later. That’s a reasonable strategy when you have capital coming in all the time, but when you don’t, there’s no cash flow to pay the bills. Ultimately, I think that’s what [closed Fifth Season].

The short version of that is timing. The timing was bad. Had we been in this position a year before, when funds were more readily available, I think we would still be in business. Had we been able to go a few months longer, get into the next cycle of the next upturn, things could be different.

There was this controversial play at the end of the [2023] Super Bowl and whether or not this penalty cost the Eagles the Super Bowl. But it wasn’t just that one penalty. It was all the plays prior that made it come down to that one penalty.

I think it could be the same for Fifth Season. We were pursuing all these different strategies. When the markets pulled back, we were a little bit more fragmented than we needed to be.

AFN: What’s a big lesson for other vertical farm startups to note?

CC: It’s so important to build the founding team when you build out the farm.

Do you hire the grower or the engineer first? Is it a farm, or is it an engineering masterpiece? The solution is, you hire both at the same time. It has to be designed from the start with people that know how to grow in a facility, and with engineers that know how to build the facility for growing. They have to go hand in hand.

The other component is accounting and finance. You’re trying to grow in an environment with real cost constraints. There are energy costs, fertilizer costs, water costs. Every drop of water that’s applied in a completely indoor facility and a warehouse has to be processed through the HVAC. Then it’s not just the cost of the water but also the energy cost of processing that water through the environment, which means there is a constraint on how much water you can give a crop in its growth cycle if you want to grow it at cost.

So it’s a trio. You need the engineer, you need the grower and you need finance because you need to understand how all these things come together to build the right products. It all comes back to unit economics.

Had [Fifth Season] had those constraints from the beginning, we might have made different choices.

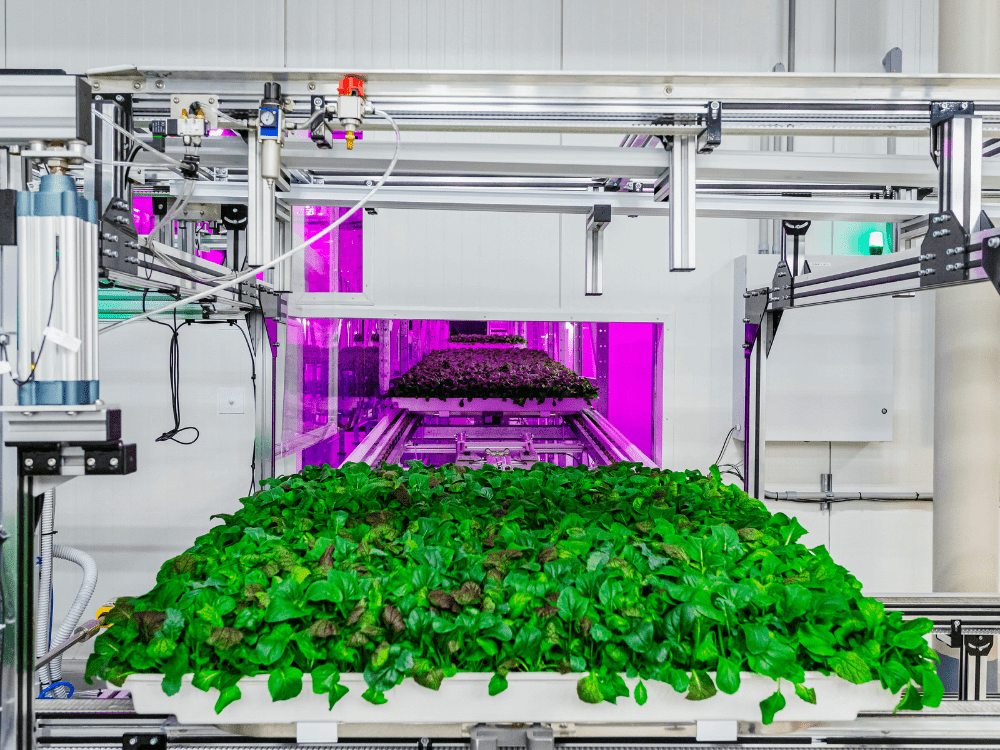

AFN: Fifth Season was known for its automation, which is a huge topic at this show. What are your thoughts on it now?

CC: Startups should be mindful of what automation they’re putting in and whether there is a return on investment.

Don’t automate for the sake of automation; carefully decide where you will automate and have a progression. If you’re building a facility from scratch, you should install the automation at the beginning and be mindful of what’s really going to help.

“Don’t automate for the sake of automation-” Chris Ceverny

[Fifth Season] was the most automated facility I’ve ever seen; it was amazing the amount of things that we had in there. But looking back, I wonder whether we should have automated all of those things from the get-go. We probably spent too much on bots that we didn’t need yet.

Automation can be both a help and a hurt. Automation you don’t want is expensive, and it’s messy. If you do it wrong, it’s costly to redo.

We had an automated line for packing salads. But it was really difficult to get that dialed in because it’s easy to crush produce in that thing. Hand-packing is more labor intensive, but a person knows whether or not they’re crushing the greens. The machine is indiscriminate: anything that gets in the way will get smashed.

One day we’ll have AI vision that can look at a tray of greens and tell us what leaves are bad and remove it. But in the meantime, we need people looking at those salads and figuring that out.

AFN: Funding has really dried up for vertical farming. How should startups be approaching this now?

CC: The funding has to match the goal you’re trying to serve.

I like the “reclaiming urban land” aspect of vertical farming. We built the farm for Fifth Season right outside of one of Andrew Carnegie’s original steel mills. We brought fresh food and jobs to an area that needs it. On the other hand, [with urban farming] you have urban utilities, urban taxes and everything else in an urban environment that if you move a few miles away, just outside of the city, the paradigm changes.

If I’m trying to compete with field-grown produce, maybe I don’t want to do that from inside of a city, which has a fundamentally different goal, such as building a national food brand that could appeal to consumers. That’s a fundamentally different goal than trying to compete with field-grown produce on the unit economics.

If you pick the right goal, and then pick funding to match it, then you’re setting the right expectations. If you have an investor that wants a quick return on investment, that might not line up with your goal. You need investors that match that vision.

AFN: You talked about efficiency vs. flexibility on the panel. Elaborate on that.

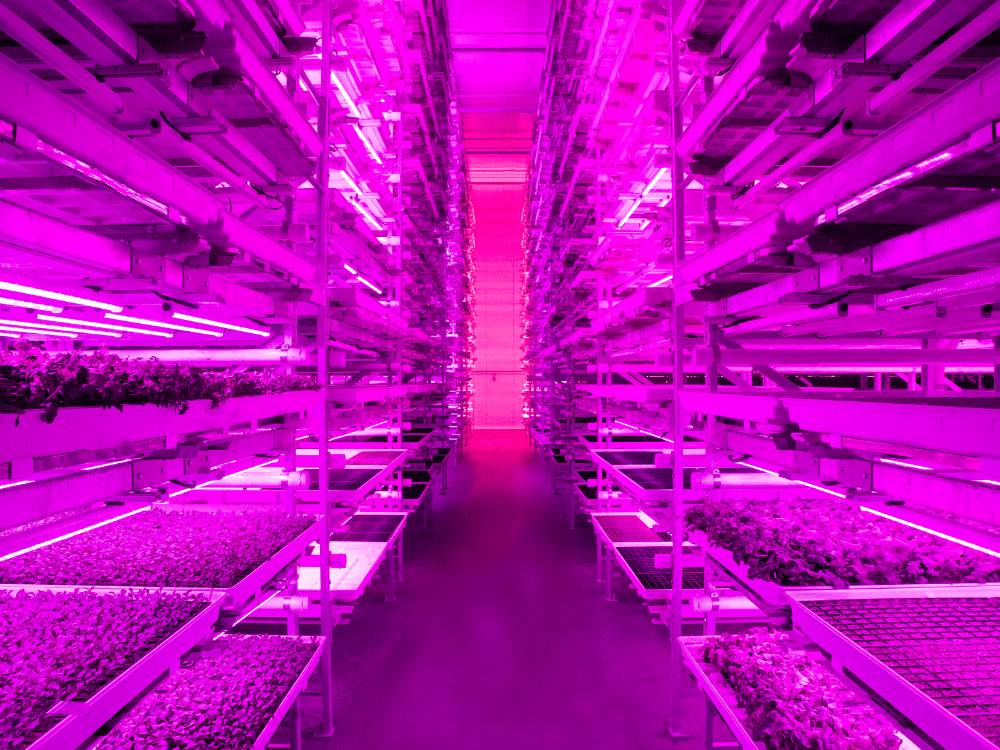

CC: [At Fifth Season] we built the farm for flexibility. When we built the farm and designed it, we didn’t know what we were going to grow. We had this idea for a rack progression: crops would start out under a tight spacing and then they would grow, which over time would need larger spacing. Well, it turns out as we went along, we wanted to grow leafy greens and pursue this salad kit strategy. So we had some inefficiencies because we had racks designed for larger plants taking up more space because there are fewer rows on those racks. So, if you design a farm for flexibility, don’t be disappointed when it’s inefficient.

That’s what I mean about lining up goals with where you’re trying to go. If you need efficiency, you build a farm for efficiency. We were going to do that in Columbus. That would have been a completely different facility from an efficiency standpoint, because we didn’t need the flexibility anymore.

AFN: Should vertical farming startups build or buy their tech?

CC: Only spend the time inventing what you need to invent; you don’t have to reinvent the wheel on everything, or inventing for the sake of invention. It’s a waste of time, and it burns a lot of capital and time when you could just buy a solution that’s off the shelf and will work.

AFN: Final advice for startups in this space?

CC: Triple-check your assumptions.

Hire a consultant. Hire two consultants. Get other perspectives and look for opinions that are counter to yours. You don’t have to agree with them, but you should listen and consider if it applies to your business. or not.

Let’s say you were trying to scale expensive berries, but everybody else tells you that’s not going to happen. You might need to know that right? You have to humble yourself and allow yourself to pivot. If you built [a farm] out with something that isn’t going to be sustainable, and it’s not going to grow the way that you plan, you have to be able to adjust.

There’s a Steve Jobs quote that says, “We don’t hire smart people and tell them what to do. We hire smart people so they can tell us what to do.” I think that’s so important when you build out these companies.

Also, talk to other growers to figure out what’s working. Learn from those of us that have failed: what we did, what we are saying that we should have done differently.

Further reading on the topic