Vertical farming’s struggles and so-called failures over the last several months have prompted a lot of questions about the sector’s long-term viability. But panelists and attendees at Indoor Ag-Con in Las Vegas this week aren’t interested in debating whether vertical farming is headed for dot-com-style implosion. Instead, the discussion has centered on what’s happened in the last few years and how to learn from these mistakes.

“It’s more about teaching,” Kyle Barnett of Indoor Ag-Con said by way of introducing his panel yesterday entitled “Failing Forward – Lessons Learned.”

The three individuals who joined Barnett onstage know a thing or two about failure. Chris Cerveny is the former vice president of Fifth Season, a US-based vertical farming startup that abruptly closed down at the very end of 2022. CEA advisor Erika Summers cited Sanabio‘s Oasis Biotech facility as her most notable experience with failure. Glenn Behrman, the founder and president of CEA Advisors, said he’s come close to failing many times during his years in the industry.

But the panel wasn’t a litany of everything that went wrong for these individuals in their vertical farming initiatives. Rather, they related their experiences and those of associates and colleagues to assemble a checklist of items others can keep in mind in order to not fail in the future.

“We felt like we were doing a lot of things right,” said Cerveny onstage. “Only in retrospect [are there] a lot of lessons that we learned that I’d like to share and hope some of you can learn from kind of the stuff that we experienced.”

Pre-launch preparations

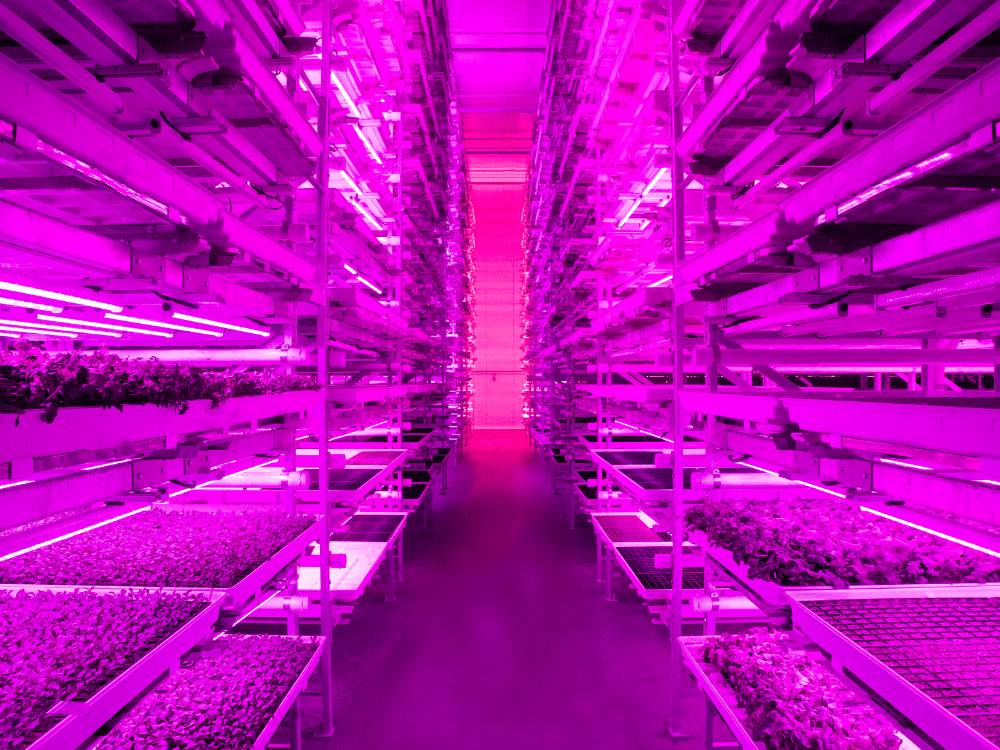

As was repeated ad infinitum, running a vertical farm is highly complex. The challenges start long before the LED lights turn on and the production of leafy greens begins. Companies must decide on a host of things, including whether to build a farm from scratch or retrofit an existing building. In both cases, they need to ensure easy access to a highway (for distribution), reliable power, and “good bones” on the structure, and they also need to be aware of everything from local laws to local temperatures.

For example, Summers related a story of air chillers at Oasis Biotech that kept shutting off due to the extreme Las Vegas desert heat outside. “We did not have environmental controls [in our farm] for about four months because our chillers kept shutting off,” she said. Naturally, this impacted production.

Summers, a mechanical engineer by profession, mentioned a host of other factors companies must consider when building or retrofitting a building for indoor farming. “I’ve seen so many clients come to me with buildings that have wooden trusses or aren’t located near a highway that can be substantial for distribution, or in a shop or facility that they can have a power upgrade. Those are things that will kill your farm from the get-go.”

Operations and technology

When the farm is actually up and running, boots on the ground are critical to operational success. Or as Behrman put it, “You can’t sit in a Starbucks and run your farm.”

This might seem counterintuitive at a time when many are pitching automation as the future of not just indoor ag but farming in general. But panelists suggested automation is only as good as the team of humans behind it.

“You have to have boots on the ground to ensure the automation is doing what it’s supposed to do,” said Cerveny. Fifth Season itself focused heavily on vertical farming robotics, though Cerveny didn’t delve too deeply into how much that impacted the company’s shutdown.

Summers said she hasn’t yet seen a company doing large-scale automation that’s been really successful. As she sees it, companies must “be strategic” about where they apply automation, which should be making operations more efficient and saving companies money.

And as noted above, automation doesn’t mean pulling a switch and letting the farm run itself.

“The one thing that I’ve always done, whether it was 20 acres or 10,000 square feet, is that I’ve walked around every day and looked at every plant,” said Behrman. “The first hour of every day was just walking around and being one with the facility. It sounds silly, but you have to be intimate with every aspect of the operation.”

“Sometimes the industry talks about removing the grower from the equation, and that we’re going to replace them with automation,” added Cerveny. “We are not there yet and that’s a dangerous mindset to be in. Everything you’re doing is about giving your growers superpowers.”

For David Farquar, CEO of vertical farming technology company Intelligent Growth Solutions (IGS), trying to mix in-house tech development and farming operations is the real challenge and why so many vertical farms have struggled: