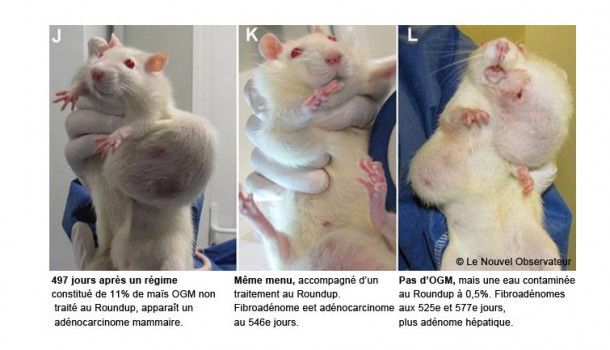

Pictures of three tumor-ridden rats line the headlines about the controversial study by Frenchman Gilles-Eric Seralini at the University of Caen in France. Originally published in September 2012 in the reputed scientific Journal Food & Chemical Toxicology, the study suggests those who consume NK603 maize, or genetically modified corn resistant to the herbicide Roundup—linked to a Monsanto strain—are at a much higher risk of developing cancer. It would be the first study to find that GMOs are harmful to mammals, and the study’s conclusions and scientific procedure raised some eyebrows of more than just Monsanto folks.

Despite where one falls within the GMO debate, strong scientific practices are the key to academic findings. To many, this study doesn’t live up to scientific standards. Others strongly protect the piece, skeptical of the forces and reasons behind the study’s retraction. Since the paper’s release, many scientists are speaking out against the study and Seralini’s procedure.

Criticisms range from “inconclusive” to “fraud,” and everything in between. Scientists and scientific reviews such as the Academics Review have poured out their thoughts, and in short, there is a long list of flaws cited. Here’s a summary of the big points:

- Seralini used rats that are prone to develop tumors as they aged.

- There were 180 rats fed the test grain, while there were only 20 rats that served as the control.

- There was an absence of necessary statistical analysis necessary to determine the prevalence of cancer development.

- There was a lack of kidney and liver function tests on the rats, leading to inconclusive results.

- The rats should have been euthanized long before the tumors were so overwhelming.

- The study’s reports focused primarily on morality rates.

Despite an overwhelming demand, Seralini refuses to release the data from his experiment.

The article exploded in popularity and was quickly distributed. Against traditional practice, Seralini distributed the paper to journalists but forced them to sign a non-disclosure agreement, precluding them to share it with scientists for a third party review. As the Economist writes, it catalyzed a serious threat for current agricultural practices:

The article exploded in popularity and was quickly distributed. Against traditional practice, Seralini distributed the paper to journalists but forced them to sign a non-disclosure agreement, precluding them to share it with scientists for a third party review. As the Economist writes, it catalyzed a serious threat for current agricultural practices:

Jean-Marc Ayrault, France’s prime minister, said that if its results were confirmed his government would press for a Europe-wide ban on NK603 maize. Russia suspended imports of the crop. Kenya banned all GM crops. The article came out two months before a referendum in California that would have required the labeling of all GM foods. It played a role in the vote, though in the event the proposition was defeated.

But after the European Food Safety Authority decided that the study was inconclusive, and after many formal complains in what some are calling an “avalanche of criticism,” Food & Chemical Toxicology announced it was retracting the study and released a public statement on Nov. 28, saying,

“Very shortly after the publication of this article, the journal received Letters to the Editor expressing concerns about the validity of the findings it described, the proper use of animals, and even allegations of fraud.”

In the meantime, Seralini has threatened to sue the journal, but no further developments have come since his threat.

Many skeptics and scientists say that the peer-reviewed system works most of the time, but in this instance, it failed. One website aptly compared the Seralini study’s retraction to the hubbub in 2010 around the Lancet’s retraction of Wakfield’s study, which linked vaccines to autism. Similar to the Lancet paper, Seralini’s study could easily be seen as fodder for anti-GMO-ers, but many would argue it is a study that is rather unhealthily modified.

Sponsored

Sponsored post: The innovator’s dilemma: why agbioscience innovation must focus on the farmer first