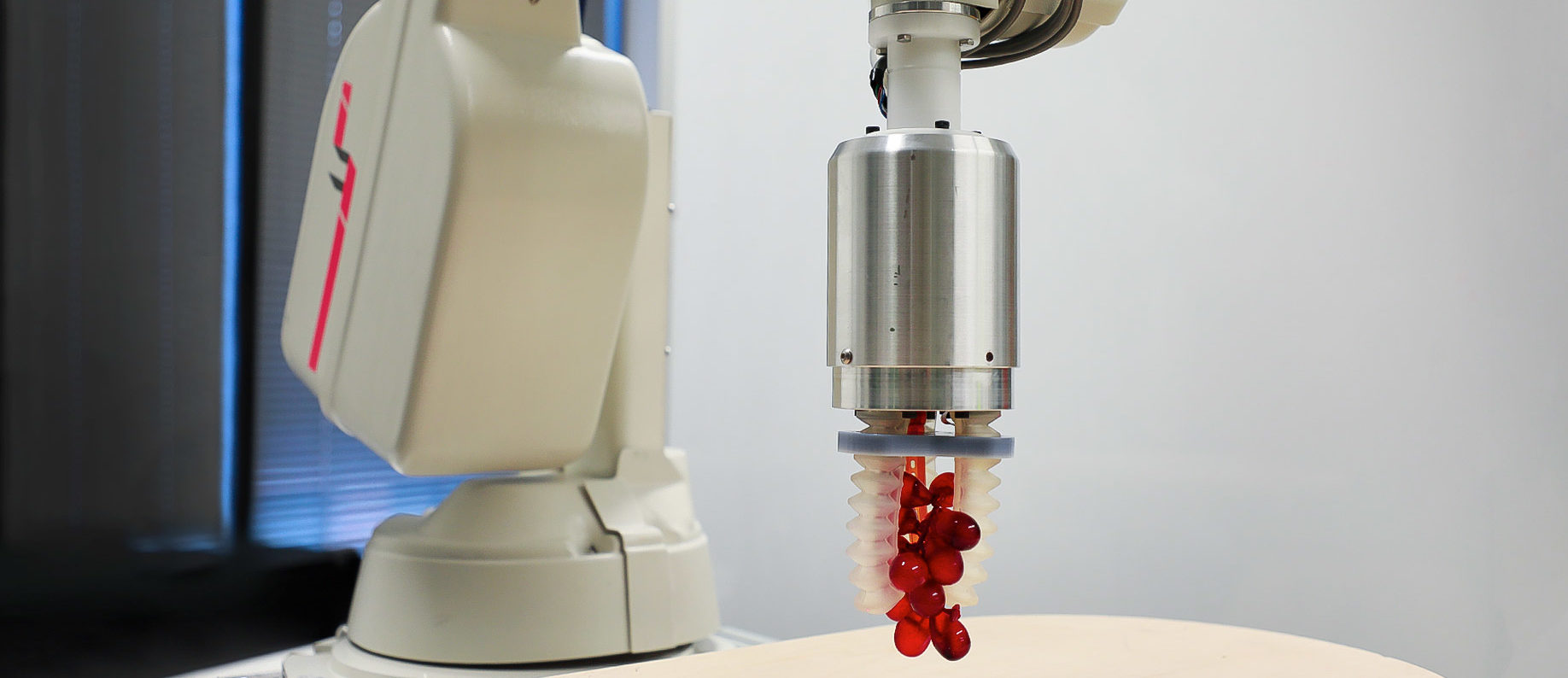

British developers have unveiled a super-sensitive robot with the claim that its almost human hand qualities allow it to pick delicate farm crops such as raspberries and strawberries.

Called Hank, the new arrival comes from Cambridge Consultants, which is part of the international Engineering and R&D services group, Altran.

Hank’s appearance on the British crop scene also appears to be perfectly timed, with many UK farmers currently preparing for life without a steady flow of European Union (EU) fruit pickers and other seasonal workers. This is due to the country’s decision to leave the EU, a process which will almost certainly significantly reduce the movement of seasonal workers into Britain.

UK farmers growing apples, berries and field crops currently employ 70,000 seasonal workers a year, many of whom come from fellow EU countries under freedom-of-movement arrangements

Hank, plus a few ‘clones’ could be the answer, especially as Cambridge Consultants says its invention is equipped to hold and grip delicate objects using just the right amount of pressure.

“He could have valuable applications in agriculture, where the ability to pick small, irregular and delicate items has been one of the industry’s ‘grand challenges’,” said the UK-based company, adding that while other robots tend to require complex grasping algorithms, costly sensing devices and vision sensors, Hank’s soft robotic fingers are controlled by airflows that can flex his fingers and apply force as and when required.

Initial farmer reaction to the new robot, however, has focused more on whether or not his highly sensitive ‘mind’ can be further developed to allow him to tell the difference between a ripe, juicy raspberry, and one which is still green and needing a few more days in the sun.

“Properly-trained human fruit pickers need to very quickly assess which berries are ready for eating before picking them, often needing to move foliage to make their judgement,” said Peter Loggie, policy manager for the National Farmers’ Union of Scotland (NFUS), adding that a successful robot would need to be able to do the same.

“Traditionally, however, computer technology has been very poor at pattern recognition, compared with humans.”

Scottish soft fruit grower, James Porter, chair of NFUS’s Horticulture Committee agreed, adding: “The reality of balancing the sort of expensive camera technology needed to match up with sensitive picking hands, plus the cost of developing such a machine, means we are unlikely to see it being commercially available any time soon.

“However, if we can put people on the moon, I am sure we will ultimately develop an automatic strawberry or raspberry picker, although I think the cost could make it unviable.”

At least Hank’s feelings aren’t going to be hurt by such a reaction, not at this stage in his development that is.

For appropriate feelings and reactions, therefore, AFN turned to Niall Mottram, head of Product Development, Industrial & Energy, Cambridge Consultants, with a request for him to address the initial response from farmers.

“Robots are not the solution to everything and they cannot substitute for all the tasks a human labourer can do,” he said. “They can, however, substitute in a cost-effective manner for some activities.

“For example, a robot won’t necessarily do that well at picking a fruit, washing it and placing it in a clamshell ready for distribution to market. But it will be able to nail one of those individual tasks, and do so better than a human.

“Robots are best suited where their parameters of operation are well–defined. What they struggle with is uncertainty, which might come in the form of a target object or its location.

“In that context, what we’ve done is to develop Hank to prove there is a path to solving this challenge with low-cost sensors. As a result, by giving Hank a sense of touch and slip just like a human hand, he is able to ‘feel’ his way to an adequate grasp.”

Asked if he thought the pace of development of robotics was starting to quicken, after what seems to have been somewhat slow progress until now, Mottram said he believed the sector was beginning to display ‘better systems-level thinking’ than in the past.

“We’re now combining clever machine vision technologies (software), with more cost–effective end effectors (hardware),” he said.

“As for how much investment is required to develop a new robot, that will depend entirely on the starting point and the volumes required.

“A development cost of $5 million to create a low volume (20-50 units) robot isn’t uncommon, although that number wouldn’t include tooling and material costs. Once all that comes into play, you could easily double the development budget to $10m.

“Set against such figures, however, it’s worth considering what happens when crops go unharvested because of labour shortages. At that point, it’s the cost of not developing robots that actually becomes significant.”

His argument is even more pertinent in Brexit Britain where UK farmers growing apples, berries and field crops currently employ 70,000 seasonal workers a year, many of whom come from fellow EU countries under freedom-of-movement arrangements. Within this total labour requirement, berry growers need 29,000 workers of their own to pick fruit before it starts rotting in the field.

With the final Brexit deal, due to be concluded by October 31 this year, expected to put an end to free-movement labour, the need for Hank and his friends to finally deliver will rise sharply.

Mottram, for one, is convinced robots will be able to cope with whatever farming demands of them in the future, urging producers to think back at the very early days of robotic use in automotive assembly.

“It seems unfathomable now that cars could be assembled without robots,” he said, suggesting that robotics in farming could easily follow the same development pattern.