Mary Poppins used to sing about how a spoonful of sugar “helps the medicine go down.” She’d perhaps change her tune if she ever met Dr. Ilan Samish, the CEO and founder of Amai Proteins — an Israeli startup lab-designing hyper-sweet, thermo-stable, zero-calorie proteins out of exotic fruits.

“The latest one is over 10 thousand times sweeter than sugar,” he tells AgFunderNews on the sidelines of last month’s Rethink Food-Agri Innovation Week in San Francisco, where Amai clinched this year’s AgriFood Tech Innovation Award for ‘Most Innovative International Startup at Pre-Series A.’

One example of these hyper-sweet designer proteins in action: “We’ve been making pina coladas,” Dr. Samish says proudly. Amai, which is the Japanese word for ‘sweet,’ has been collaborating with food and beverage conglomerates like PepsiCo, Danone and SodaStream (as well as biotech companies like Merck and Lonza) to refine and stabilize taste profiles, testing their proteins in a wide variety of conditions and flavors.

A Spoonful of Proteins

What he takes from his bag today, however, is a little less tropical: a generic plastic water bottle, filled with a clear liquid.

Inside, he says, is indeed mostly water, mixed with a solution of roughly half sugar. The other half is one of his lab-designed super sweet proteins, designed based on proteins of exotic fruits via a process called Agile Integrative Computational Protein Design (AI-CPD) and fermentation; there’s also a dash of acidic lemon juice thrown in to help stabilize the flavor and prevent the whole thing turning too sweet.

Dr. Samish hopes that tiny doses of proteins like these — milligrams rather than spoonfuls — could soon serve as a cheap and healthy way of replacing sugars or other sweeteners in soft drinks, snacks, or, indeed, possibly medication. While these proteins activate our sweetness receptors, our guts will absorb them as workmanly proteins. (Right now, these sweet proteins are for research and development purposes only. And occasionally for serving up to journalists asking too many questions…)

There are good reasons for weaning suppliers, consumers, and Mary Poppins off sugary stuff: “Sugar kills more people than gunpowder,” Dr. Samish warns, with a sternness capable of silencing even the chirpiest of fictional British nannies. And with a dark sprinkle of his own lyricism, he adds that “gunpowder does it quickly; sugar does it slowly.”

This is grim but true. According to the World Health Organization, the number of people who have diabetes surged from 108 million in 1980 to 422 million in 2014, while worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975. Many public health experts link these trends to heightened global intakes of addictive and calorific sugary snacks and drinks. Both diabetes and obesity can, in turn, trigger a whole host of related health problems, not least elevating the risk of heart disease and strokes — the world’s two most common causes of death. The current mass market options for alternative low-calorie sweeteners is not much to smile or sing about either. A 2018 report conducted by the American Heart Association found that many of these options have “undesirable effects of satiety and perception of hunger” and “increased taste preference for sweet foods,” as well as promoting an “increased perception that more dietary calories can be consumed.” They also warn of a “dearth of evidence on the potential adverse effects of LCS [Low-Calorie Sweeteners] beverages relative to potential benefits.”

A ‘Crazy Guy’ Curing Food

The medical and pharmaceutical response, Dr. Samish has long believed, has been disproportionately pointing in the wrong direction. “Huge amounts of funding are spent on curing diseases relating to sugar intake,” he says. “I decided to devote my time into curing the food that causes these diseases.”

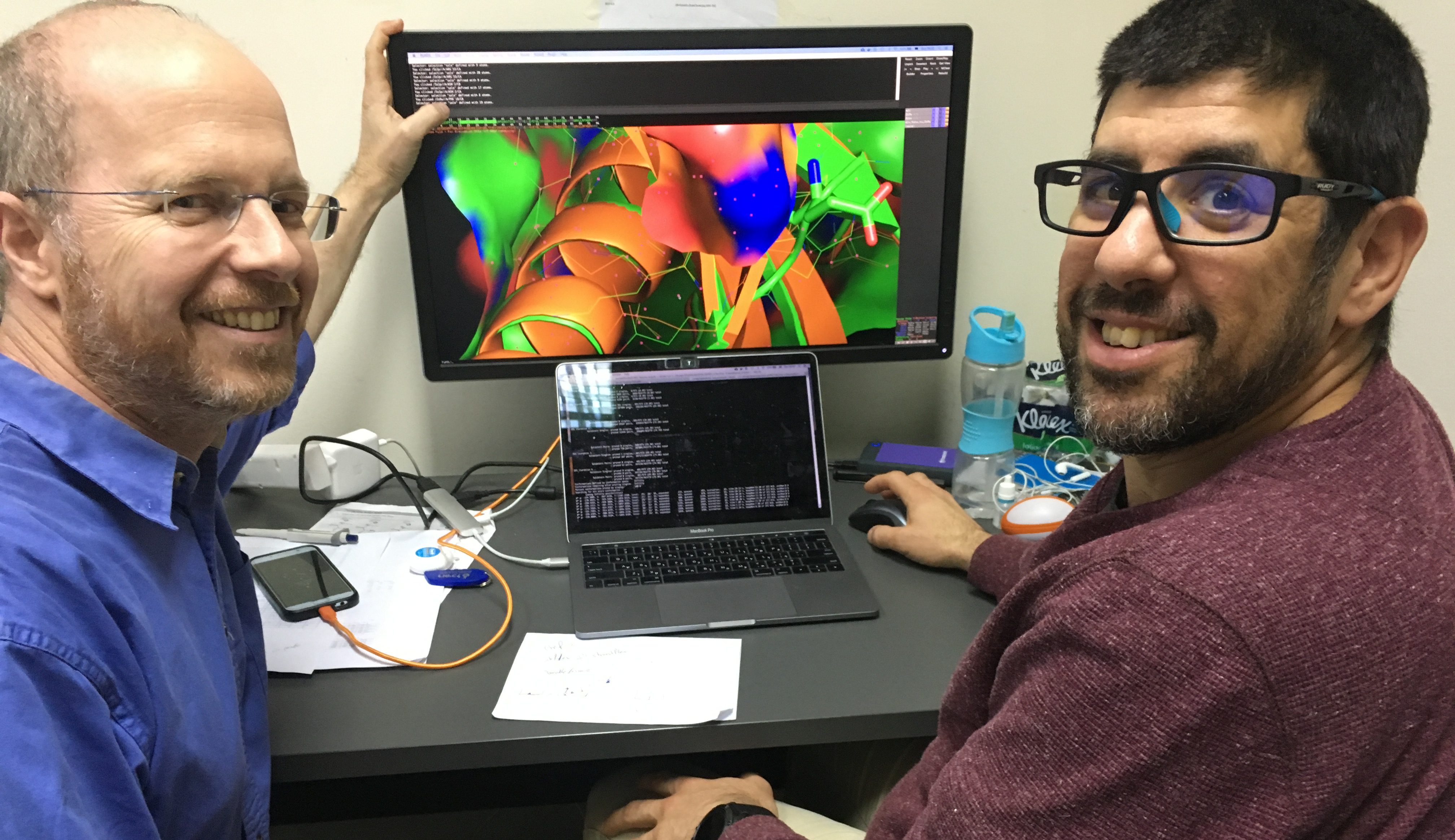

Before going into business, Dr. Samish was a researcher and lecturer in the emergent field of computational structural biology, founding and chairing conferences like 3DSig. He also co-wrote and edited a book on the subject, which has proved a touchstone for those entering the field. One visible legacy of his research years is the presence of the people he previously studied with (and under) featuring on a glittering scientific advisory board at Amai. Among them, William de Grado of UCSF, a pioneer in the field of computational protein designs, and Michael Levitt, a Nobel laureate for his work in structural computational biophysics.

Still, Dr. Samish describes himself as “a crazy guy” for leaving the comfort of academia in 2016 to seek success in the frantic world of startups. His port of call was the Kitchen Hub, an Israeli government-backed incubator for early-stage food companies. “All companies came with a prototype, and I just came with a deck of slides. They didn’t know what to do with me,” Dr. Samish laughs. “Somehow I got some funding!”

Amai has so far raised $1.4m of seed funding from The Kitchen Hub and the Israel Innovation Authority, receiving a further $120k in cloud computing grants from Amazon and Google. His company is now fundraising for its Series A round, where it hopes to raise a further $10 million; it has also teamed up with several major European food and beverage multinationals in search of EU grants.

The Amai team also reports that it is moving production from a 10-liter glass fermentation method to a scalable 100-liter stainless steel fermentation, which should help ready the company for mass market entry. The US regulatory context is looking promising, with the USDA and FDA’s announcement in March of plans co-regulate cell-cultured food products. “I hope that the regulators will take this opportunity to encompass within the new guidelines all the proteins produced by fermentation,” Dr. Samish wrote in a blog post in response to the news. “Whether these are nature-identical or designer proteins adapted to the mass food market.”

Differentiation

When designing the sweetness of proteins, the measurement of its sweetness is mostly reliant on hedonic sensory evaluation and sweetness threshold tests. Put crudely, can a human tongue detect and grade the sweetness of a given weight of a substance, which could be a tiny percentage of a solution? If it can detect a tiny trace, it’s sweeter than a substance where you need more traces to be detected. This scale, benchmarked to sugar, is measured in Brix.

There are alternative natural, hyper-sweet proteins in use already that have had market access for decades which are a few thousand times sweeter than sugar by this measurement. For instance, there has long been plenty of buzz around brazzein, mabinlin, monellin, miraculin, and curculin,” according to Dr. Samish. In particular, the sweet protein thaumatin is used in hundreds of food products. These are all found near the equator, where their sweetness is a survival strategy to lure mammals and birds into transporting their seeds to less shady jungle areas. So far, they cannot successfully grow through agriculture. Dr. Samish argues that while each natural sweet protein is a different ball game, taste profiles are often compromised; their thermostability, shelf lives, and supplies are limited; and their price is too high. That can make scaling tricky and even unsustainable.

What makes Amai’s offering different, he says, is the team’s use of fermentation to produce even sweeter proteins in a lab after redesigning of their molecular structure via AI-CPD. The team downloads exotic sweet protein coordinates from an online-available protein database; then they re-engineer them to suit a harsh food milieu. With the fermentation, they “back-engineer the DNA gene which is expressed in microorganisms,” becoming brewers growing yeast, from which they harvest their protein.

That process allows stability in a wider range of conditions, for a more extended amount of time. For instance, Amai’s proteins, Dr. Samish claims, can maintain their structural integrity and sweetness profile throughout pasteurization processes, opening the way for its use in dairy products. With its cloud computing software, the team have been designing their own unique strings of amino acids which are 70-95 percent identical to sweet proteins found in nature; the result, according to the Amai website, is a product “highly similar to the original protein yet confers beneficial properties such as taste, thermal-stability, acid-stability, shelf-life, expression yield.”

Let’s see about that. When he passes over the taster, there is a look of cautious expectation.

Does it taste … supercalifragilisticexpialidocious?

Well, it is certainly sweet … But nothing to send you onto the next flight to Tel Aviv in search of another fix. It seems to taste more like just plain, unremarkable sugar; as good a thing as any to help the medicine go down.