While adoption of precision ag tech is certainly on the upward trajectory in Europe, some segments of farming are still hesitant to transition, according to Rasmus Emil Hansen, co-founder and CEO of Denmark-based startup PerPlant.

“You have a segment of farmers that are cost sensitive and they prefer to buy something that fits into what they already have. They’re not going to go out and buy the newest sprayer just to have it, because it’s quite a big investment for them,” he tells AgFunderNews.

Founded just last year, PerPlant hopes to bring more farmers into precision farming by offering just that: tools that are easier to use and don’t require operational shifts in order to integrate them into the daily grind.

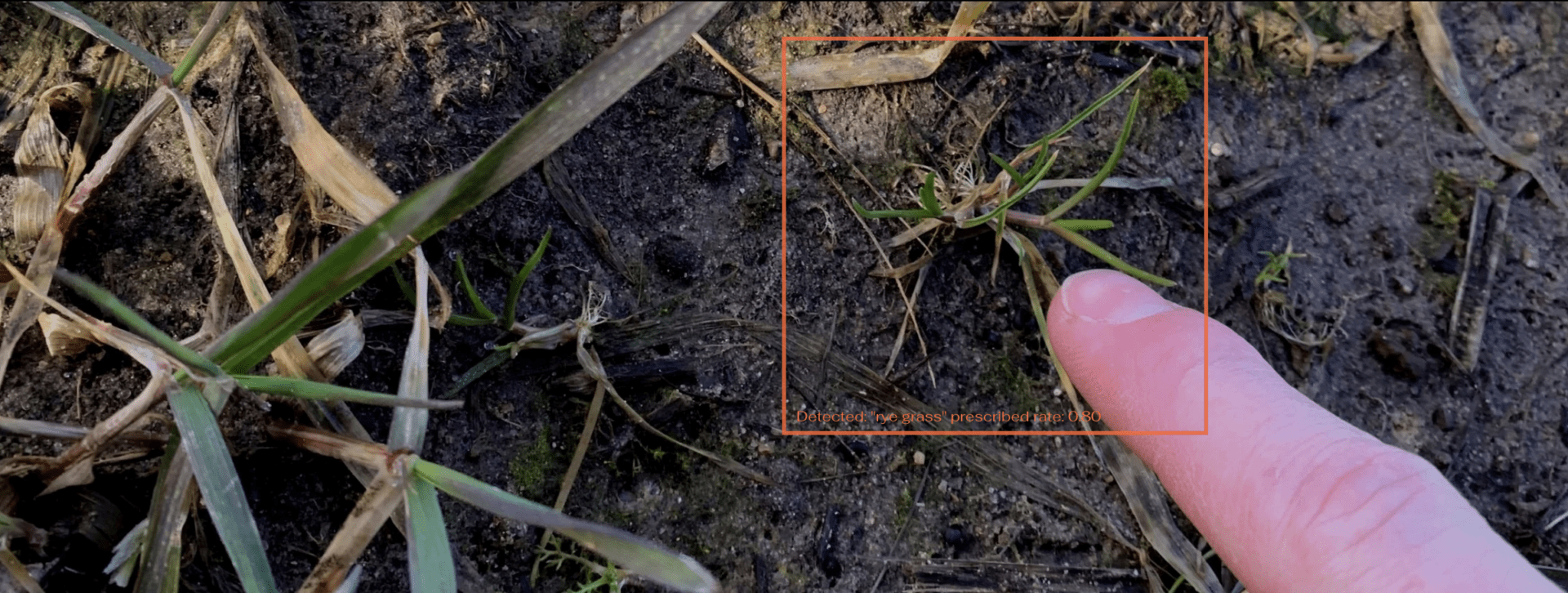

PerPlant’s setup uses a high-definition camera that attaches to existing farm equipment, in this case a sprayer. Once the camera captures field data images, AI immediately processes the data and generates in real time prescription rates for spraying. Since the PerPlant system is directly integrated with the sprayer, the latter can immediately execute according to the prescription.

Hansen says one of the big differentiators is the ability to monitor plants “with centimeter-level precision” as well as process high-definition data on the edge and generate insights “exactly when farmers need them” instead of after the fact.

Recently, PerPlant completed a $670,000 pre-seed round from VCs Foortprint Firm and global VC Antler.

Read on for more about Hansen’s (RH) farming background, the founders’ motivations for starting the company and what’s next.

AFN: What’s the PerPlant origin story?

RH: Sumod [Nandanwa, PerPlant CTO] and I actually had two different motivations when we started the company.

Sumod grew up in India and has been working with precision technology, including sensors and drones, for different seed manufacturers in India. He has approximately eight years working in that [area] and also for some startups.

One of his passions has been to build fighting robots and he has been a champion in Southeast Asia for many years. His design of these robots has been quite progressive. But he always wanted to become an entrepreneur himself, and so he moved to Stockholm to finish his degree in mechanical engineering.

He did some research on autonomous drones in agriculture. One of the challenges in agriculture with drones has been the ability to detect something — for instance, late blight in potatoes, or weeds — and also spray at the same place fast enough. This requires a certain level of processing power of the algorithm to take these granular images of disease and process them fast enough to spray exactly where you want to spray.

[Sumad] studied this and found an algorithm that could do it.

But he realized when he wanted to then commercialize this idea that there were some challenges, especially in Europe, in terms of scaling drone technology in agriculture, due to legislation.

So he came up with this idea: take the same technology and just place it on a tractor and connected to the sprayer to allow for automated spraying. That’s the idea he thought he wanted to commercialize, but he has a technical background; he didn’t have a commercial one. So he was looking for someone who would complement him.

Me on the other hand, I have grown up on a farm and I’ve always loved being out in the fields, helping my family farm.

When I studied at Copenhagen Business School, I did some studies on machine vision models and their commercial impact based on the decisions these AI-generated systems take.

I also I did some work at as a management consultant, worked for McKinsey and Deloitte and helped out larger enterprise clients with implementation of AI-based software solutions. During that time I also had a son, and I realized along the way that helping big companies earn even more money wasn’t really aligned with my inner compass. There are bigger problems out there.

I sort of got this wake up call when [my son] was born. When he’s the same age as I am today, it will be 2050. And I just want to tell him that at least I tried to somehow change that direction [of the planet].

So I quit the job as a consultant but I didn’t at that point know exactly how what direction would I go. That’s when I joined this entrapreneur program [Antler VC]. It was a Nordic program, so Sumad came from Stockholm, I came from Copenhagen and they matched us together. Then we did some iterations around whether we fit as a team, if we complemented each other, had the same sort of vision about where to take the company. We arrived at an early IP and got the investment, and since then it’s just progressed.

AFN: What’s your big differentiator?

RH: The real edge that we have is really in the software we build, where we collect data and process it. And it’s not just collecting data or what the sensor is detecting. We also collect soil data (we source it from external sources), we collect satellite production maps – the five-year history of the field and how it’s produced yield-wise.

We [the ag industry] haven’t had yet a solution where you could combine all these data, and do so on the edge, in real time. This is really where [precision ag] is going; it’s about being very accurate when it comes to showing what’s really needed in the field.

AFN: What segment of ag are you targeting with this system?

RH: There’s a large group of farmers in Europe with farms from around 200 hectares to about 1,000 hectares. This is the last group of farmers that has not really started doing precision farming and trying to reduce chemicals more efficiently.

We were curious on why that is. They have sensors, they have drones, they have sensors mounted on back of the sprayers or self-driving spray robots. But at least in Denmark, for instance, 90% of farmers are still not using any precision ag.

So it appears you have a segment of farmers that are cost sensitive and they prefer to buy something that fits into what they already have. They’re not going to go out and buy the newest sprayer just to have it, because it’s quite a big investment for them.

AFN: Describe some of the current challenges with precision ag tech.

RH: You have satellites that can help monitor as well, but the satellites, even though they’re always accessible, still have complications in terms of being very precise for disease or fungus or weed detection needed for reducing herbicide and fungicide.

Then you’d have drones, which are very precise. You could hire a consultant to come out, monitor your field and get very precise in trying to see the fungus. But the friction for doing this is quite high. You’d have to hire a third party to come out 16 times during the season. That’s costly for the farmer but it also but also creates friction for the farmer’s planning — having control of timing is very important for farmers.

So no one has really fulfilled the need for this last group of farmers where there is something that’s easy for them to use, doesn’t have the friction of a drone but has its precision, and is priced at something where they can actually get started quickly.

That’s what exactly what we had designed and what our vision is to democratize precision farming for more sustainable agriculture, creating something which is designed to be easier for this group of farmers to use. Not just technology wise but also pricing wise.

AFN: Who are your major competitors?

RH: The closest competitor we’ve seen is a company called Augmenta. They were acquired by CNH Industrial not long ago. But the crops they are focusing on are not the crops you would have in the Nordic region, so the company wasn’t present at all in the market we’re currently in.

AFN: Where will the pre-seed money go?

RH: That is really to commercialize the first product on the market. We have done several tests now. We are ready with the first version [of the sprayer] which can detect [weeds] and also create prescription rates and have the sprayer spray exactly where it’s needed.

We’ll start initially in this region [the Nordic countries] where we are commercially commercializing the product; the next step is to to go more international, into more of the European countries.