As world leaders gather this week for COP 26 in Glasgow, UK, all eyes are on solutions to climate change; and the need to make global food systems more efficient is clearer than ever. One core inefficiency of the food system is food waste, which is the focal point of one of UN Sustainable Development Goals, as one third of all food is wasted and not eaten.

In the US, a significant portion of food waste happens at the retail level, when grocery stores throw out food they can’t sell after a certain point; either it’s spoiled or it’s been damaged. Earlier this month, Do Good Foods launched in order to address the 10.5 million tons of food that’s wasted at the retail level, of which 35% going to landfill or an incinerator.

Founded by Justin and Matthew Kamine of the family-run Kamine Development Corp, the multi-billion dollar infrastructure company, the team are no stranger to logistical or agricultural challenges. Yet it was still a long journey to figure out the best approach and after six years, the brothers announced a $169 million investment from asset manager Nuveen.

The result is a unique business model with a consumer product that the brothers say could eliminate most retail-level food waste in the US.

A closed-loop system

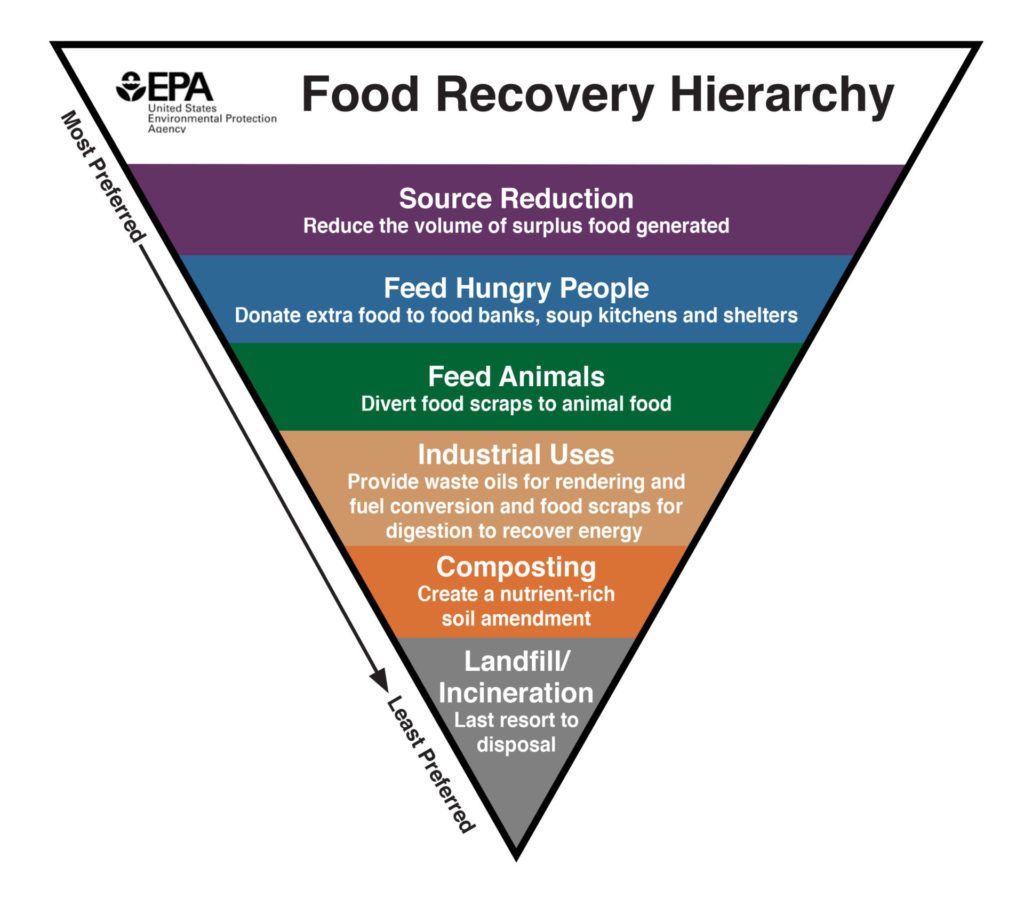

At the foundation of Do Good Foods’ business model is the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Food Recovery Hierarchy, a prioritization of strategies to help organizations manage food waste. According to the Agency’s inverted pyramid (see image), after source reduction and feeding other humans, the next most impactful thing companies can do with food waste is to divert it into feed for farm animals.

In keeping with that, Do Good Foods takes surplus food from partnering retailers, ideally from cold storage to preserves the nutrients, every two or three days, free of charge. At its own facility the company turns the surplus food scraps into animal feed. The company is currently producing feed for chickens that mimics the animals’ natural diet.

Chickens raised on this feed are eventually processed and sold to consumers under the Do Good Foods brand, closing the loop on the process. The company says that every chicken fed and sold via this process equates to four pounds of food waste diverted from landfills, and that purchasing and eating these chickens can help consumers reduce their carbon footprint. Do Good Foods verifies its carbon calculations with third-party consulting company Ruby Canyon.

Fighting food waste at scale

Speaking recently to AFN, co-CEOs Justin and Matthew say the six-year journey was necessary to land on the right approach, and that it wasn’t until the last year that the consumer product model was landed on.

“A lot of the effort that went into the last five years was making sure that we found a process that, on the manufacturing side, we could scale very rapidly,” said Matthew. “We didn’t want to find a solution that could only work as a one-off or as a small solution. We wanted to find something that we believe we can rapidly deploy across the country.”

“I think there were a lot of learnings that I drew up as to how you do [this process] at such a large scale,” added Justin. “Everything from the logistics coordination with the supermarkets to the processing of that food into the animal feed – and then really the connectivity to their brands, and finally empowering the consumer to be a part of that solution; each one of those steps was a journey in itself.”

Joining the Kamine brothers in senior management is chief strategy officer Sam Kass, who served as chef and nutrition policy advisor to former US President Barack Obama and is now a partner at agrifoodtech venture capital firm Acre VP.

Kass says that the process would be easy to do if the startup were only looking to sell its chickens back to a handful of high-end grocery stores in Brooklyn or San Francisco. “The hard part is figuring out how to do this that so that you can reach people all over the country, at a price point that you know […] the majority of Americans can afford,” he says.

Another question at hand is whether consumers are motivated enough to buy a new brand of chicken because it’s better for the planet. An oft-cited survey from Brian Roe, Faculty Lead for the Ohio State University Food Waste Collaborative, notes that 77% of respondents felt guilty about wasting food, but 51% said reducing food waste would be difficult.

However, consumers also expect brands to help in addressing climate change. A recent Deloitte survey of 10,000 respondents across six countries found that 40% of the public are “more likely to be actively involved in social issues, and many are changing their buying patterns or encouraging others to do the same.”

Do Good Foods has yet to release information about what price the chickens will sell at or where they will be available in the US – though Justin said its retail partners will adopt the process nationwide “from Texas up to Ohio, down to Virginia.” They say the pickup from retailers has been positive so far.

“The recognition that creating this closed-loop system with any product and [putting] a brand back onto the retail shelf really showcases to the market that sustainable infrastructure and climate-forward foods are what the consumers and the corporations really desire,” said Justin.

For now, chickens will be the only Do Good Foods product available for purchase in grocery stores. Future products are in the works, though the company isn’t giving away any more specifics at this time.

Simpler tech for fighting food waste

Kass says there are a few unique aspects of this model, the biggest one being its simplicity in terms of what it requires from the parties involved. For retailers, its “a no-brainer,” since grocery stores normally pay money to have their food waste removed and Do Good Foods doesn’t charge for pickup or require any extra work or change in process other than putting the food in the bins.

Kass suggests this way of doing things makes it easier for a solution like Do Good Foods’ to fit into existing operations and supply chains. That ultimately makes it easier to scale and, hopefully, to have a bigger overall impact.

“We’re not asking people do change a lot,” he told AFN. “We want to solve all these big problems, but the fastest way to do that is to make the solutions simple and easy to do.”

Do Good Foods’ first production facility is located in Fairless Hills, Pennsylvania. At 85,000 square feet, it has the capacity to take in and convert 160 tons of surplus food from approximately 450 grocery stores every day, which equates to roughly 60,000 tons annually.

The company will replicate this model across the US over the next five years.

Do Good Chicken, meanwhile, will be available at restaurants and supermarkets in early 2022.

*With additional reporting by Louisa Burwood-Taylor*