The agriculture industry is slowly but steadily switching on to carbon sequestration, its potential environmental impact, and the opportunity for it to provide additional income streams for farmers.

But when it comes to adoption of carbon-storing methods and rewarding those who implement them, there are still plenty of pieces of the puzzle yet to fall into place.

One of the challenges facing would-be ‘carbon farmers,’ and the companies that seek to provide services to them, is actually understanding how much of the stuff is in their soil in order to make decisions about how, why, and where to implement restorative techniques.

To date, the most accurate way of doing this is to take physical soil samples and send them off to labs for testing. This can be expensive and time consuming, requires boots on the ground, and can’t always give a holistic picture of soil health or carbon content.

The team at Boulder, Colorado-based Cloud Agronomics thinks it has come up with a viable alternative. The startup recently raised $6 million in seed funding from SineWave Ventures to expand its digital agronomy and carbon monitoring products in the US, Australia, and Brazil.

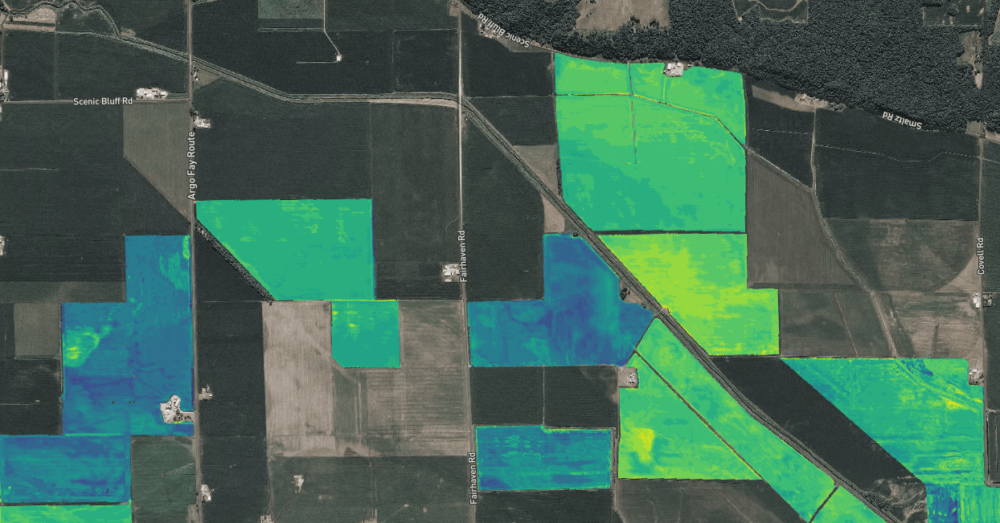

By using hyperspectral imaging — which can measure light from across all bands (wavelengths) of the electromagnetic spectrum, compared to the human eye’s three bands — Cloud Ag is able to determine the presence of carbon and other nutrients in the soil, as well as potential diseases in plants, from the light they reflect.

AFN caught up with Cloud Ag CEO Mark Tracy — a former Cargill and Indigo Ag exec — and Jack Roswell, the startup’s co-founder and chief operating officer, to find out more.

AFN: What is your technology, and what problem are you trying to solve with it?

Mark Tracy (MT): The problem [with non-hyperspectral imaging is it] often just simply tells farmers a measure of green-ness. They’re thinking: ‘I’m tired of being told my plants are stressed, but not what I should do about it.’ Cloud Ag took a technology [partly] developed by NASA and realized that same technology could be applied to plant and soil health, and that it could be used for diagnosing disease.

The challenge, however, was how to scale that tech outside the lab and put it into the real world, to look at real fields growing real crops. It’s like taking the line scanner out of your copier, putting it 8,000 feet above the document you want to copy, and flying it at 200 miles per hour and expecting to get something useful out of that. It needs incredible calibration, across many bands, at altitude to see wide swathes of farmland all at once. It needs to overcome the tech hurdles to do that, and also work on the ground to figure out what those signals actually mean for soil health overall.

We’re the only company in the world to be able to do that through hyperspectral imaging at commercial scale in the field. Other people throw around the word hyperspectral, but really what they’re doing is just advanced multispectral.

It is in fact aircraft, and not satellites, we use. NASA did attempt to put one into orbit and couldn’t overcome those calibration problems. Our ability, flying an aircraft, is we can see 1,500 meters across so we can capture a wide swath of farmland that would just not be possible with a drone. Typically we’re flying at around 8,000 feet.

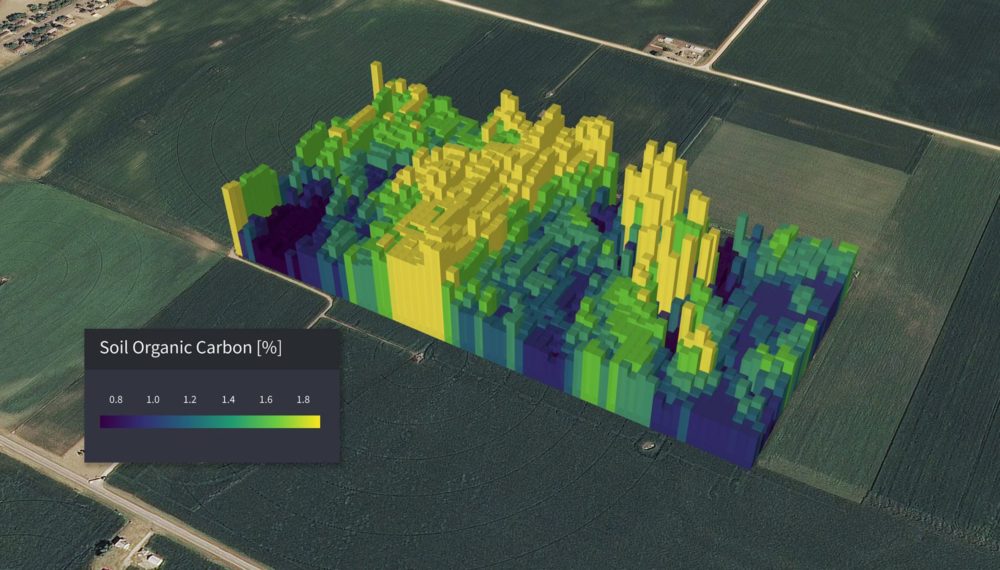

Why that matters is we’re able to see 200 to 300 times more data per square foot than anyone’s ever seen of agriculture before. We collect a terabyte of data for every hour we fly. It’s the first tech to ever sense the amount of soil carbon remotely. If you’re not looking at all the different bands made available by hyperspectral imaging, you can’t extract these kinds of insights, ultimately.

Jack Roswell (JR): I think going off of what Mark said, when you look at a high level are able to unlock ag’s potential, and really unlocking precision ag. I know it’s a big claim — aerial imagery for ag, especially satellite analytics, has existed for decades — but even today the best imagery available is just that, a pretty picture of farm. Really what we’re solving is, there’s a reliance on soil sampling and the only way to get that information today is to send a human out into the field. We’re still relying on humans walking in fields collecting leaf and dirt samples and sending them to the lab.

The idea is, if we can scale this type of tech, and get to that gold standard at labs and land grant universities in the US, we can provide the same analysis – quantifying soil and organic carbon, nutrients, for every plant and every piece of soil in the world. That allows us to go into markets traditional agtech couldn’t access.

How does Cloud Ag’s solution measure up to physical soil sample testing?

MT: We’ve had several large companies announce they pay farmers to sequester carbon – Indigo, Cargill, and now Bayer. The biggest barrier to scaling and making [carbon credits] work, one of the most significant, is exactly what Jack is talking about: Taking physical soil samples to the lab. For a 5,000 acre farm, imagine how many soil samples are needed to be taken to have real scientific rigor in building trust [in a carbon credits program]. The error rates can be as high as 50% to 60%. It can vary from square meter to square meter. So the ability to fly remotely and tell, down to the individual acre, and then resurvey it during the year really unlocks the kind of scale that wasn’t possible before.

What Cloud Ag did this Spring was take physical soil samples across 11 different states in the US. Those samples came from diverse locations — Texas, as far north as Minnesota, Indiana in the east and west to Colorado — so a tremendous diversity of soil types, climates, and different croplands were represented. At the same time, we flew over the same locations with our hyperspectral imaging — and that was the basis of showing our model has less than a 10% error rate.

We believe we’ll be able to replace physical soil sampling over time. We understand people will need to build confidence in our solution, and we need to demonstrate that to regulators and government.

When building the management team, why did the co-founders decide to bring in outsiders — such as Mark — to lead the company at this early stage?

JR: I’m one of two co-founders [of Cloud Ag] from Brown University. While we there doing independent research into this optical technology we realized, if we were able to scale it outside the lab, it could have a resounding impact in this industry – one of the last to be disrupted by machine learning. This data is incredibly difficult to collect and calibrate [before reaching] the stage to analyze the data. The real [intellectual property] and value proposition is not only being able to collect this data, but we’re building out one of the largest datasets for ag, across two growing seasons so far.

Agtech is unique because it demands deep subject matter expertise and industry relationships. Few with those backgrounds can cross over into complex digital scientific analysis. So we’re incredibly excited to have Mark. Our executive chairman is Jaymin Patel, who has been CEO of several companies. Our chief scientist is Brown University professor James Kellner, and we have a team of about 18 now with very deep knowledge how to translate optical data into analytics that are actionable within this industry. We’re flying over fields, measuring light that plants are reflecting at a very high resolution, and [through an] incredibly complex process that turns that data into the outputs we’re discussing in a way that is very simple and actionable for our customers.

There are pros and cons to government involvement in carbon credits markets. Read more here

It boils down to the opportunity we saw. We’re a technical founding team that is trying disrupt and advance such a large industry. What we saw was this application of our tech, we were in awe of it – but we didn’t want any hubris to pull us down. We saw that if you combine incredible tech with legacy relationships and industry connections, you go to market much faster and solve problems at the highest level – as opposed to going through the laborious process other agtech startups may go through. It creates a sense of validity.

Who is your target customer?

MT: We’re not selling direct to farmers. We’re B2B model, paid directly on a dollar per acre basis for the ground we’re covering. and based on type of analysis we’re providing. So by and large, a number of large companies of the type I mentioned [agribusinesses are our customers] although I should also add it’s insurers, federal agencies that are interested in this type of analysis, and also financial institutions with capital to work in the commodity markets.

Have you raised any previous investment? If so, who are your other investors?

JR: There’s also a follow-on [in this seed round] from a prior angel round, from a syndicate of several angels from the Valley in addition to some current public executives. We also have Alumni Ventures Group and several others [as investors] as well.

How are you using the seed funding?

JR: First and foremost, to continue to grow and build out our team. We have a very strong core team, but we’re targeting growth in our geospatial arm. And that goes to show our growth opportunities too, and our priorities. We want to have a global presence, so we’re using this capital to grow our business globally. In addition to the underlying hyperspectral data, we’re integrating satellite imaging, IoT data, and more to extract more information from that imagery. Another example of that is while Cloud Ag started in US, we’re working with partners including Microsoft‘s AI for Earth to expand in Brazil and Australia.

Why are you targeting Australia and Brazil in particular for expansion?

MT: Australia is a leader in actually trying to promulgate a standard for carbon sequestration. A number of parties there are interested in remote sensing, and Australia has great diversity of agriculture. Our initial focus is on global large row crops such as wheat, but there’s potential for things like sugarcane and cotton as other examples. That fits hand-in-glove with Brazil – I used to do a lot of business there when I was with Cargill in cocoa, coffee, and so on.

One other thing is to have, as a North American company, a Southern Hemisphere growing season to diversify our business, providing analytics 365 days a year.

What other applications are possible with your technology?

MT: We can also fly over fields and tell customers the level of nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus down to the square meter per field, which allows customers to maximize their yield while minimizing their input costs. But this is really just the beginning. We believe it will eventually tell us about the quality of physical grain while it’s still in the field prior to harvest. [Perhaps those crops] won’t need to be taken to a 1950s brick-and-mortar location [for quality testing]. Farmers can take it to market already knowing the quality they have.

Got a news tip? Email me at [email protected] or find me on Twitter at @jacknwellis