Des Moines-based startup FarmlandFinder has raised a $3 million seed round led by Chicago-based agtech VC Cultivian Sandbox with participation from Iowa Farm Bureau’s Rural Vitality Fund and Next Level Ventures. It previously raised an angel investment round from Ag Startup Engine and others. The startup offers a subscription-based platform to help with the farm selling and buying process through the use of data like soil mapping and hyperspectral imaging.

‘What could possibly be the pain point here?’ you may ask. Or, ‘aren’t there enough real estate websites to help people purchase agricultural properties?’

If you’ve ever tried to purchase a farm, chances are that you found it to be a frustrating and complex process. I should know. I purchased a farm last year after roughly 18 months on the hunt. If you aren’t a farmer, it’s worth understanding some of the current land tenure trends plaguing the industry and why this startup caught the idea of heavyweights like Cultivian Sandbox.

As people set to inherit farmland show less interest in taking over the family business but an unwillingness to break a sentimental bond through a sale, the industry has seen an uptick in the number of non-operator landlords (NOLOs). The USDA uses this term to refer to absent landlords, often heirs of farmland who are based in faraway cities.

Today, 40% of farmland is leased and roughly one-third of that share is rented out by NOLOs. This number is even higher in heavy agricultural regions such as Iowa where half of the farmland is maintained through leases. Having someone who has never farmed as your landlord can be unappealing for some farmers, as well as having to work with a property management company that oversees the land in the owner’s absence. Tillable’s ‘Hassle-Free Lease’ aims to modernize the farmland lease process.

Although leases provide a flexible and realistic way for beginning farmers to launch their operations and to build their farming expertise, leases are an unreliable foundation for a long-term farming business that requires capital investment, equipment, infrastructure and more.

Even if you are ready to buy a farm, you will probably have a hard time finding one. Between 2018 and 2021, just 10% of the 911 million acres of agricultural land in the US will change hands. Half of it will transfer through inheritance, gifting, or closed sales, while the other half will be sold in the open market.

And even if you find a farm for sale, chances are you probably can’t afford it. Land prices have increased 1,600% since the 1980s farm crisis and increasing consolidation among individuals who view farmland as an investment has created substantial financial barriers.

Enter FarmlandFinder

“I grew up on a dairy farm in Northwest Iowa. It’s disheartening when you hear that your neighbor’s land sold and that you didn’t even have a chance to get your foot in the door,” FarmlandFinder founder and CEO Steven Brockshus told AFN. “We are trying to increase access to information and to create transparency in a traditionally opaque industry.”

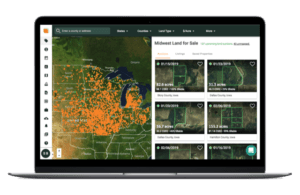

FarmlandFinder’s web app allows users to view farmland properties for sale at no charge. To access the premium version of the service, where the goldmine of data awaits, users must pay $50. For that price, however, FarmlandFinder will provide them with a wide variety of data about the purchase as well as related farm properties that sold within the last few years. This includes things like soil mapping, satellite imagery analysis, yield-related data, and more.

FarmlandFinder’s web app allows users to view farmland properties for sale at no charge. To access the premium version of the service, where the goldmine of data awaits, users must pay $50. For that price, however, FarmlandFinder will provide them with a wide variety of data about the purchase as well as related farm properties that sold within the last few years. This includes things like soil mapping, satellite imagery analysis, yield-related data, and more.

As Brockshus puts it, the startup is pulling pieces of what precision ag has done for farmers over the last decade and the best aspects from residential and commercial real estate, and delivering a tool specifically for farmland sales.

“We think this creates a level playing field. Before, the only people with access to this info before were institutional land investors and professionals who have teams of people acquiring farms,” he explains. “All [FarmlandFinder] does is give the everyday farmer, landowner, buyer, or even absentee landlord, the same level of sophistication.”

Some sellers may see little incentive in tapping a platform like this given the scarcity of farmland for sale, but Brockshus points out that many sellers may still be concerned about being taken advantage of. Numerous data points can provide an objective way to equalize the negotiation process.

“Another practical sense is that some landowners who do know local farmers in the area also go to church or school together or are friends. It can make it hard to give their property to one person and not the other. Selling farmland is always a difficult decision whether a parent has passed away or it’s out of a financial need,” he explains.

The new funding will be used to make key hires in the leadership and sales side of the business. For now, the startup is focused on farmland sales but sees potential opportunities to leverage its data democratization capacity for other aspects of the agriculture industry.

If there’s anything we’ve learned about farmers and technology, however, it’s that farmers can get prickly when it comes to how their data are being used. A seller may be dissuaded by the idea that the buyer will be able to evaluate the property at a more granular level compared to the traditional process of viewing the property and haggling over a price.

As one of Brockshus clients once said, “I like being nosy without being nosy.”

“I come from Northwest Iowa, one of the most conservative parts of the country along with the conservative ethos of the ag industry. It’s almost diametrically opposed to technology that increases transparency or access to information,” Brockshus says. “When you push for disruptive change in an industry, it can be displacing to landowners who have this mindset about how it should be done in traditional ways with auctioneers or brokers. The tried and true way of doing things.”

He is also quick to point out that FarmlandFinder is not getting individual data from individual landowners or farms. Some parts of the service are currently only available in 12 states throughout the Midwest while other services are available nationwide.

As a fifth-generation farmer, he feels well equipped to deal with any backlash. After all, some of the folks who take offense to the idea of more transparency in land deals could very well be his neighbors.