Editor’s Note: Shmuel Rausnitz, is the agrifood tech analyst at Israel’s non-profit innovation promoter Start-Up Nation Central and AgFunder’s Israel report partner. Here he writes about his concerns relating to the FDA and foodtech entrepreneur’s tendency to oversimplify consumer demands and needs across demographics.

I’m increasingly aware of a tendency among food tech entrepreneurs to overgeneralize consumer needs and identities as a means to back up the market potential of their innovations. But it’s not just over-eager entrepreneurs doing this; the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) is also using low-resolution data to paint broad-brush pictures about the consumer, causing startups and corporates to considerably overestimate the size and compatibility of their market.

An important instance appears in the FDA’s Nutrition Innovation Strategy, published in March 2018. The strategy aims to implement nutrition policies to combat chronic diseases that afflict swathes of the American population, such as obesity. “Almost 40 percent of U.S. adults are obese, and if you add overweight adults, the percentage goes up to a staggering 70 percent,” reads the report. Overweightness in the USA is a national problem, and these simple figures reflect the pervasiveness of the condition. There is no reason to doubt them.

However, when the FDA describes its plans for reducing this figure, the agency starts to make assumptions about consumers— i.e. among whom are the overweight majority of Americans.

“Consumers [are] interested in finding easier ways to identify healthful foods by looking at the labels when food shopping.” Consumers, the FDA conveys, also “want ‘clean labels,’” i.e. comprehensible ingredient lists. They are in fact already benefiting from “updated labels based on current science,” that “provide more information that empower them to choose healthful diets.”

According to the FDA’s wording, the nutrient-deficient American population is health-aware, sufficiently knowledgeable, and motivated, but long accustomed to misleading labels and jargon. The FDA’s Nutrition Innovation Strategy points out the general problem and offers a set of solutions.

But how many of that 70% of overweight US consumers think as the FDA portrays? The FDA does not tell us how many of the 70% are consumers “wanting” transparency in food options so they can “choose” a healthier diet. If the FDA is basing its policies on the assumption that all consumers need or even seek the same changes in order to adjust their own eating habits, the agency’s prospects for success are a big unknown.

If bureaucratic and entrepreneurial incumbents want to direct food innovation toward combating health pandemics like obesity, they have to be guided by clearer notions of the consumer and deploy appropriately specific data.

A breakdown of the obese American population into socio-economic demographics reveals that the FDA’s strategy probably will not be efficacious. In the US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report” from the end of 2017, researchers found that during 2011–2014 “obesity among adults was lower in the highest income group,” at about 31% of the group, than in the others, at 41% and 39% respectively. The report also showed that “obesity among college graduates was lower [28%] than among those with some college education [41%] or high school graduates [40%].”

The research shows that while obesity is not at all limited to socio-economic status, it prevails more among lower- and middle-income earners and among those who never attained higher education. In other words, the FDA’s target consumer indeed could be the person with disposable income and college education but is more likely to be the person who is financially limited and unexposed to enlightened concerns. This latter group probably is less knowledgeable and preoccupied with assessing food labels and ingredients in the interest of crafting a healthier diet. So while such measures will probably hit a portion of the American obese, it will almost certainly fail to affect the rest and therefore will not stem national overweightedness.

The FDA’s assumptions could also be misleading innovators and industry corporates that base their products and business strategies around the vague notion of a willing and able overweight consumer. Of course, entrepreneurs and businesses also reach these conclusions on their own as well.

At the World Agri-Tech Summit and Future Food-Tech conferences in San Francisco this past March, an FDA representative reasserted this image of the consumer awaiting policy and tech innovation for the benefit of nationwide health conditions, and on-stage discussions among industry leaders revealed the same problematic assumptions. At one point during the conference, a group of representatives of global Food and Health corporates discussed how supermarkets are poised to become centers for personalized nutrition. They pointed to Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods as a case in point.

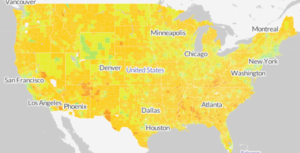

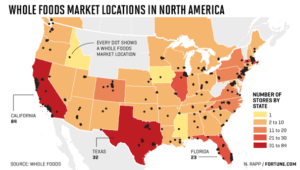

But what no one acknowledged was the primary socio-economic demographic of the US to which Whole Foods caters: the health-conscious and financially able, not everyone. The locations of Whole Foods stores across the US suggest that its target consumer is the higher median income earner: the chain, which is in every mainland state, is in its cities, where median household incomes are highest (see images below). The old disparaging moniker “Whole Paycheck” reinforces this apparent prioritization of consumers. As the Amazon–Whole Foods tech–food marriage digitizes and personalizes shoppers’ experience, it could impact only this socio-economic stratum of American consumers, at least in the short to medium term.

![]()

There is nothing necessarily wrong with focusing primarily on one socio-economic class of consumer – and likely those affiliated with the regulators and entrepreneurs themselves, and these advances are almost certainly not intentionally discriminatory. But by omitting finer distinctions in industry discourse and government planning, Food and Health incumbents in the private and public sectors alike are bound to mistarget and be disappointed by limited results once their strategies and technology are deployed among American eaters under the pretense that proportions like 70% of Americans could benefit.

As long as low-res figures and generalizations about consumers typify the discourse of the food industry, discussions will remain both shallow and imprecise, leading to miscalculations in go-to-market strategies and missing large segments of the population just as in need of solutions.