Like many regenerative and restorative agricultural practices, agroforestry is a newish term for an ancient concept.

Cultures around the world have for centuries relied on traditional land-use practices that link trees, crops and livestock together. This intersection has provided critical access to food, fuel, medicines and other necessities.

Modern agriculture stifled agroforestry for decades in favor of mono-cropping. Fortunately, that is beginning to change as around the world farmers, ranchers landowners and rural communities re-introduce practices into their operations.

There are numerous reasons, financial, ecological and otherwise, to adopt agroforestry. It is also increasingly seen as a critical part of fighting climate change.

But what does it entail and who should practice it?

Read on for a quick guide to all things agroforestry.

So what exactly is agroforestry?

The United States Department of Agriculture defines it as “the intentional combination of agriculture and forestry to create productive and sustainable land use practices.”

The United Nations’ Food Agriculture Organization (FAO) gets even more specific, calling agroforestry “a collective name for land-use systems and technologies where woody perennials (trees, shrubs, palms, bamboos, etc.) are deliberately used on the same land-management units as agricultural crops and/or animals, in some form of spatial arrangement or temporal sequence.”

The common element here is the presence of trees (and shrubs) in crop and livestock farming. And yet, agroforestry is about much, much more than trees. Through various practice methods (see below), it can boost food security and income for farmers and rural communities while simultaneously protecting and restoring biodiversity and wildlife.

As World Agroforestry (ICRAF) notes, “Most trees have multiple uses, including cultural ones, and typically provide a range of benefits.” Agroforestry seeks to leverage these uses to the good of people, animals and the planet.

What are the different types of agroforestry?

FAO lists three main types of agroforestry systems:

- Agrisilvicultural systems combine of crops and trees. Alley cropping is one example of this.

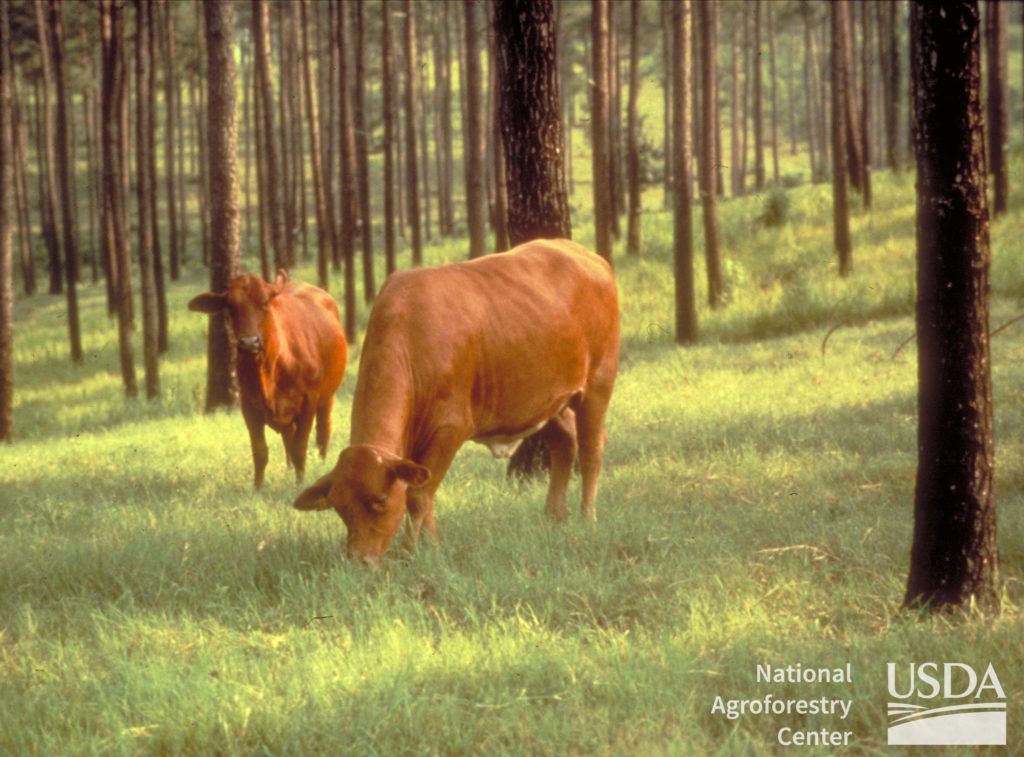

- Silvopastoral systems combine forestry and grazing of domesticated animals on pastures or farms.

- Agrosylvopastoral systems integrate trees, animals and crops.

There are several agroforestry methods within these systems:

Alley cropping involves planting agricultural crops between widely spaced rows of trees or shrubs. Some examples include hay between pecan trees or wheat between chestnut trees. The idea is to provide income to farmers while the trees mature.

Silvopasture is the practice of managing trees and grazing livestock on the same land. Trees can provide timber, fruit, nuts and fodder for animals. They also provide shade and shelter to the animals, which can reduce stress from heat, cold wind and heavy rain.

Windbreaks are linear plants of trees and shrubs to protect crops, animals and soil from snow, dust, wind and other elements.

Riparian forest buffers are natural or re-established areas along rivers and streams made up of grasses, trees and shrubs. These areas can intercept agricultural runoff before contaminates water and also aid against erosion. Trees and shrubs might produce a harvestable crop that provides growers and landowners with additional income.

Forest farming, also called multi-story cropping, produces high-value crops such as herbs or mushrooms under managed forest canopy that can provide the ideal level of shade plants need.

Syntropic farming, also called “dynamic agroforestry,” involves arranging plant groupings so they can develop into productive systems that don’t require inputs. It’s frequently thought of as process-based agriculture rather than input-based agriculture.

How can agroforestry help agriculture?

The benefits for humans, animals and the earth are numerous. Among other things, agroforestry can:

- Provide additional income for farmers, ranchers and landowners

- Protect animals, people and crops from extreme weather events

- Sequester carbon

- Keep agricultural runoff out of streams and lakes

- Increase biodiversity and wildlife habitat

- Improve pollinator habitats

- Increase economic vitality for rural communities

In some cases, agroforestry may provide a more accessible way for farmers and landowners to adopt climate-forward practices. As Propagate co-founder and CEO Ethan Steinberg recently told AFN, “There’s more efficiency on the agroforestry side, [and] the costs are less aggressive than other climate solutions.” [Disclosure: AFN’s parent company, AgFunder, is an investor in Propagate.]

Is agroforestry new?

Nope. While the term itself was coined in the 1970s, cultures around the world have practiced various agroforestry techniques for millennia, albeit under different names.

The practices of integrating trees, crops, and livestock virtually disappeared in the 20th century as Big Ag moved towards monocultures and commodity crops and agriculture and forestry became two separate entities.

Agroforestry, as we know it today, was originally outlined in the early twentieth century but largely ignored for decades. It wasn’t until the formation of the International Council for Research in Agroforestry, now known as World Agroforestry, that it joined the list of sustainable agricultural practices that could counter the negative environmental impacts of the green revolution.

Which regions practice agroforestry?

It happens all over the world and takes on many different forms.

In Nepal, for example, farmers are returning to agroforestry practices with initiatives like the World Neighbors program. This is improving food security and biodiversity as well as benefiting women farmers.

“Programs that utilize agroforestry are key to improving the food security of households, as they help meet some of the nutritional needs of people,” Rakshya Shah, senior livelihood programs manager at IUCN-Nepal, recently told nonprofit Monga Bay.

World Agroforestry notes that in Central America, farmers may plant “more than 20 different species of plants on plots of no more than one-tenth of a hectare, each with a different form, together corresponding to the layered configuration of mixed tropical forests.”

These systems might contain everything from papaya to a lower layer of bananas, a shrub layer of coffee, and ground cover like squash. The benefits include not just a wide range of food but also shade for people and animals, improved soil health, and less erosion.

World Agroforestry also operates projects throughout the rest of Latin America, many parts of Asia, and Eastern, Southern, West and Central Africa.

Recently, the U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded The Nature Conservancy and partners $60 million to fund a five-year project advancing agroforestry in multiple US states. The project is one of 70 awards that the USDA is funding through the Climate-Smart Agriculture and Forestry Partnership Initiative.

These are just a few examples of agroforestry around the world.

What are the challenges to wider adoption?

Like many other types of sustainable farming, adopting agroforestry can prove financially challenging for farmers and landowners. As is the case with practices like cover cropping, a return on investment may not be immediate, which presents financial barriers to adoption.

The practice of agroforestry is also at odds with the foundation of modern-day farming, which relies on single-species land use and monocultures. Agricultural policies typically support the commodity crops grown in such systems, providing various incentives and tax breaks.

FAO points out several other challenges that have to be addressed in order to accelerate agroforestry adoption. Those include underdeveloped markets, a lack of awareness and education about agroforestry and under-developed markets for tree products and crops compared to commodities.