Swiss drone imagery company Gamaya has raised SFr 3.2 million ($3.2 million) in Series A funding to develop its hyperspectral imaging sensor and analytics software platform.

Sandoz Family Foundation, the Swiss family office that’s part of the Novartis group which spun off its agribusiness unit to become Syngenta, led the round. It was joined by the chairman of Nestle Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, Seed4Equity, a social impact fund, and Swiss venture capital firm VI Partners.

Through the use of drone imagery, the company provides farmers with alerts about pests and disease, yield predictions, and prescriptions for input application rates. Its current platform services corn, soybean, and sugarcane growers.

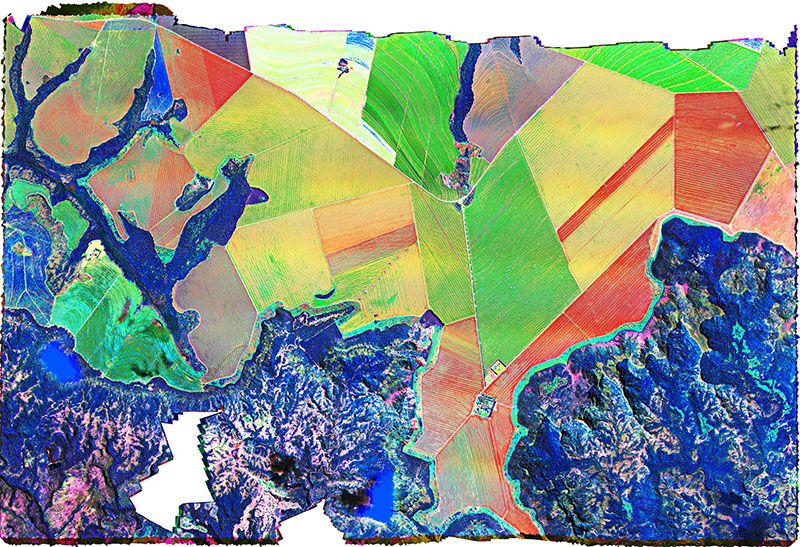

Gamaya differentiates itself from others in the drone imagery space through its hyperspectral sensing technology; the majority of drone imagery companies use multispectral images.

Hyperspectral imagery has been available for 20 years, but it’s been an expensive exercise constructing the equipment, hiring developers, and analyzing the data, so has mainly been used by large research institutes, space agencies and the military, according to Igor Ivanov, chief commercial officer of Gamaya.

Gamaya is partnering with the Belgian Nanotechnology Research Institute IMEC to produce affordable hyperspectral sensors based on a design the Gamaya founders developed out of Swiss Federal Technological Institute in Lausanne (EPFL). The novel design can show over 40 bands of light instead of just the four — red, green, blue, infrared — provided by multispectral cameras.

Multispectral cameras can measure generic characteristics such as if a plant is healthy or not, but hyperspectral images can go one step further, and diagnose the exact reason for that state. That’s because the extra bands of light it can detect can be associated with specific physiological traits within the plant.

“Multispectral imagery is largely limited to enabling analysis based on the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NVDI) and cannot, for instance, distinguish or classify weeds,” said Ivanov. “With our camera and data analytics platform we can collect an order of magnitude more information and give more detailed insights into crop health. We can provide, for example, detailed diagnostics of nutrient deficiencies, or the presence of weeds.”

The sensor is not Gamaya’s end goal as a business however, it is just the company’s “enabling technology,” said Ivanov. “Our core expertise is in the analysis and interpretation of hyperspectral data. We have a very advanced sensor, that we were forced to develop because there wasn’t anything suitable available,” said Ivanov.

The company’s main intellectual property is in its analysis of this hyperspectral imagery using artificial intelligence to produce information about the plant physiology.

To develop this analytical product for a specific issue, crop and region, Gamaya needs ground samples from each region to input into its algorithm. Early adopters or trial customers are helping to provide these, according to Yosef Akhtman, CEO of Gamaya.

“Once this is done, no further sampling is required and the product can be deployed regionally,” he said. “The products can be further generalized and scaled across wider regions once sufficient statistics are acquired. In the future, we are planning to implement a platform that would provide local agronomy consultants a simple workflow for the development of custom analytical products that they can then provide to their respective customers.”

Gamaya will sell sensors along with an integrated software subscription to intermediaries such as crop consultants, agronomists, and chemicals companies. It’s also decided to focus its initial go-to-market strategy on Brazil where farmers are under more pressure to increase efficiencies than in the US, and also where there are three growing seasons a year to test and iterate the product.

“The US market is, of course, tremendously important, but also immensely complex and competitive. Being based in Europe, we feel that we have a better opportunity to explore other important markets, such as Brazil, where we can consolidate and validate our technology before bringing it to US. Most likely, we will be looking for local, well established partners to enter the US market ones our technology will be sufficiently mature,” said Ivanov.

Getting started in Brazil has not been easy, however; import procedures are challenging and the working attitude of many Brazilian businesses is very different to that in Europe, which can make it a difficult working environment, said Ivanov.

Have news or tips? Email [email protected]