European food tech startups are on course to have raised between €750 million to €1 billion in 2018, according to different estimates. That will be around a 40% decline on 2017 funding levels.

When you take out 2017’s largest deals — including Europe’s leading food tech startups in the food delivery segment such as Deliveroo, and HelloFresh — there will be some moderate growth in funding. But European food tech startups will still lag the global food tech ecosystem raising just 16% of global food tech funding between 2014 and the first half of 2018, according to a report from DigitalFoodLab, a corporate consultancy in France. The report points out that Europe is home to 25% of the global agribusiness market.

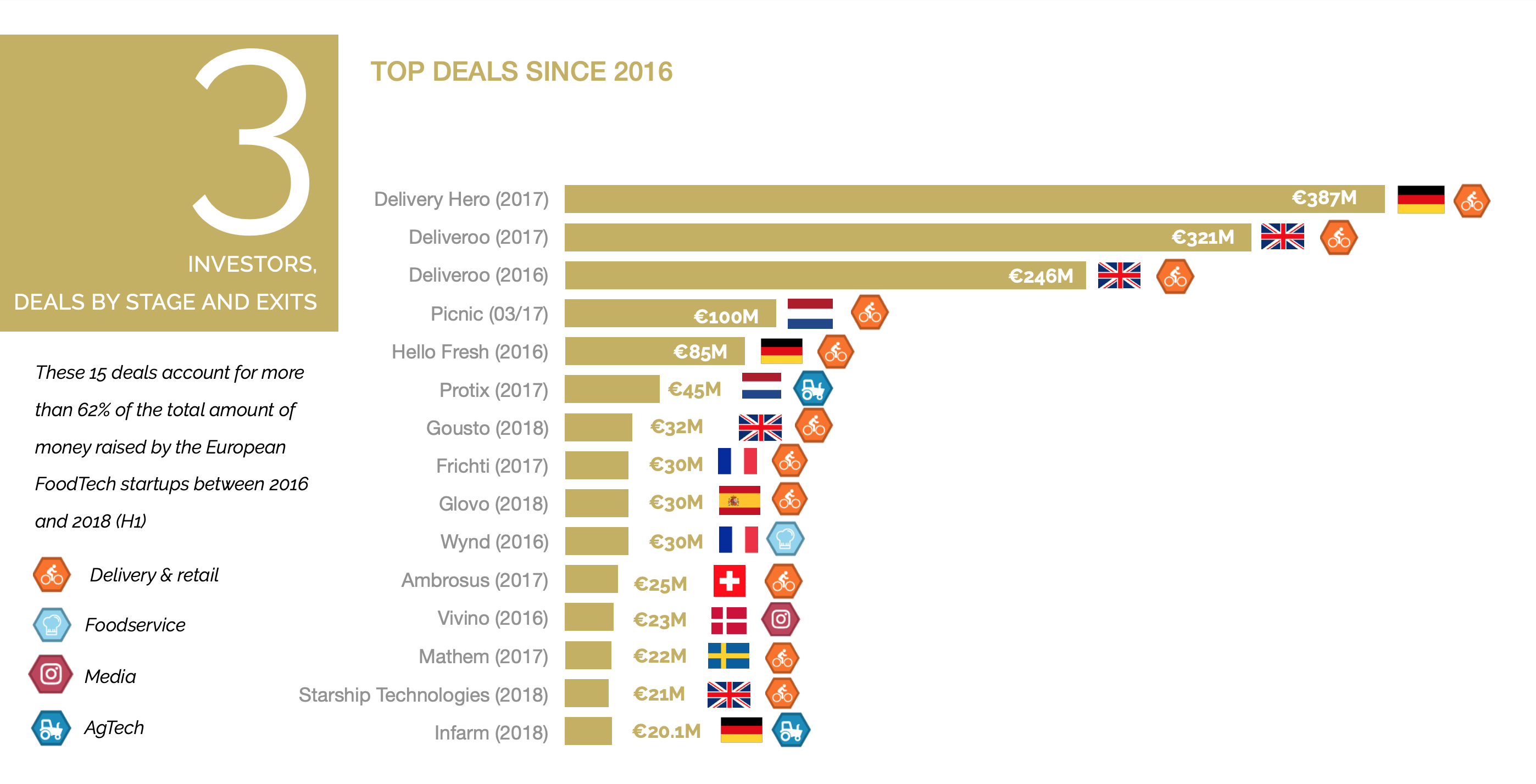

Sixty percent of the €4.2 billion raised during that period was concentrated in the coffers of three companies: restaurant marketplaces Delivery Hero and Deliveroo, and meal kit startup HelloFresh.

Add in Just Eat and takeaway.com, and this set of food ecommerce businesses have raised a combined €3 billion and are now worth a combined value of €21 billion, which is a 7x return in five years, according to a separate report by local VC Five Seasons Ventures.

These are great exit multiples and a signal of a successful ecosystem, according to some investors, but DigitalFoodLab is not as impressed with the success of these startups.

“Each of these three European giants is among the world leaders in Delivery & Retail. Though, none of these startups has “invented” its own business model. Delivery Hero and HelloFresh were born from the German startup studio Rocket Internet, specialized in copycatting successful (US) startups. While Delivery Hero has grown rapidly by taking over brands such as Foodora and FoodPanda, HelloFresh has become the world leader thanks to the US market,” reads the DigitalFoodLab report.

“If we consider that FoodTech startups are both externalized R&D and the future of current agri-businesses (either through M&A or by replacing them), we can only be worried about Europe’s future as a food powerhouse,” reads the report.

But wait; European Food Tech Innovation is Thriving?

Speak to others in European food tech and they’ll tell you the industry is thriving, albeit with challenges.

Maarten Goossens from Dutch agrifood tech fund Anterra Capital points out that while last year’s dollar funding levels represented just 15% of global levels, Europe was more active in terms of the number of deals closed at 31% of the global landscape.

“When we started Anterra in 2013, there was already a healthy number of food tech startups in the US, and that was led by the fact that the US, in general, has a more entrepreneurial ecosystem, that’s engrained in the culture; European investors have in general been more risk-averse. But if I look back at the last few years in Europe, I’d say it’s catching up to the US, just three years behind, with a healthy funnel of earlier stage companies being developed of which circa 1,000 got funding over 2015 to 2017,” he tells AgFunderNews.

The European food tech ecosystem is even starting to mature, Goossens added, with a few notable companies reaching beyond Series B stage raising significant amounts of capital across the food supply chain such as Dutch insect farming group Protix ($50m), French indoor farming group Agricool ($42m), Germany’s Infarm ($33m) and Dutch grocery delivery startup Picnic ($100M).

Later-Stage Funding Challenges

There could be a challenge for these startups as they reach later stages, however. “Europe does have a problem when it comes to later stage capital, specifically for Series B to D funding rounds when larger amounts of capital are required while the risk of failure is still significant; there’s a gap in those investment stages across all tech industries,” Goossens cautions.

Goossens says the distribution between early stage and later stage capital in Europe is out of balance, there is 14 times more capital available for later stage startups in the US than in Europe. “If you compare Europe and the US relative share of global VC funding — 15% vs 45% — you’d expect that to be a factor of three. The lack of later stage capital will remain an issue until bigger pools of capital turn their eyes to Europe.”

This appears to be a challenge across European venture capital, according to PitchBook’s Q3 European report. “From our perspective, the major difference (with the US) is a current lack of widespread VC support or ability to do €100 million+ deals. This has become a staple of the US VC playbook but is still relatively rare in Europe,” reads the report.

While Europe’s startups raised record levels of funding in 2017, much of that came from foreign investors, according to PitchBook, highlighting a 23% year-over-year drop in fundraising dollars and a 15% drop in the number of funds closed in 2017. PitchBook MD Trafalet indicated to the Financial Times that Brexit was a key consideration in the lacking ability of European VCs to raise capital. The data company predicts that the number of funds closed will have continued to fall in 2018, but that VC firms are raising larger funds, keeping total fundraising at a similar size (~€8.2bn).

Distinct Startup Investment Ecosystems

Alessio Dantino, CEO of London-based Forward Fooding, believes that the challenge for Europe’s food tech industry — and perhaps venture capital overall — is not a lack of capital, but more how that capital is organized.

“The European food tech industry is behind but starting to thrive. In my opinion, the real challenge funding wise is not the lack of capital but fragmentation and investing culture.

In general, the level of sophistication of investors is lower than in US; there are less professional investors and different regulations of what defines a professional investor for each country doesn’t help either. How investors approach startup investing is also different,” Dantino told AgFunderNews.

Europe might be a single market — for now — but each country has clearly different ecosystems for startups. And the journey for a startup in any European market is not as clear-cut as in the US where startups typically follow the similar route of attracting seed stage funds from specific types of investors, perhaps joining an accelerator and then moving onto a wealth of larger, growth stage VCs to mature to the next level.

“There are ‘small’ funds/super angels for each country and very few EU-based cross-country funds that look at investing big checks in fast-growing international businesses; most bigger deals are primarily done by a mix of PE, CVCs, family offices and funds of funds,” says Dantino.

This handful of dedicated venture capital funds focused on the food value chain based in Europe include Anterra, CapAgro, and Five Seasons, as well as a growing number of accelerators including Startupbootcamp Food Tech, which recently graduated its first cohort in Paris, StartLife out of the Netherlands, and SmartHectar in Berlin. (Find more here.)

“In Germany, there are very few startups but they are really well funded when they are; the country has an ability to make giants,” said DigitalFoodLab’s Matthieu Vincent. “The UK has a very balanced ecosystem with everything from unicorns to smaller projects getting funded. France is a paradox; there are a lot of startups but so few of them are funded; we only have about three or four food tech startups that have received more than €20 million in funding.”

French startups struggle to find funding because the corporate venture capital industry is lacking and the traditional venture capitalists in the country are nervous of the food sector, particularly as they’re used to investing in software platforms and ecommerce with 40% to 50% margins, according to Vincent.

For German startups, Vincent argues that there’s no clear location for them to be based — such as London in the UK and Silicon Valley and New York in the US. However Berlin is slowly emerging as the center for startups in Germany, he admitted.

The Netherlands, the third most active market in Europe for food tech funding in 2017, according to DigitalFoodLab’s report, has all the factors necessary to create a successful startup ecosystem, according to Vincent. It has a great agricultural university in Wageningen, access to capital including Rabobank, and lots of talent. “The Dutch food tech industry has grown very fast and it’s very impressive compared to the size of the country,” he said. The country represents over 5% of the region’s total food tech funding between 2013 and 2018.

Different Cultures, Different Languages

Language is a problem in Europe across industries and the food industry is no different. While startups and investors typically speak English, food company executives and farmers are much less likely.

“In France, if I’m doing a talk for a big retailer, they very specifically ask me not to use too many English words in it,” says Vincent.

Kevin Camphuis from Shakeup Factory in France says that scaling a startup across Europe is a challenge. But this can also create huge opportunities if you do it right.

“Europe is 20 countries, languages, regulations and above all cooking cultures. Each country has it’s own value chain, local retailers and suppliers. You thus need to be deeply inside each of them to adapt to each local environment, consumers expectations and business rules if you want to scale successfully.”

“It explains why delivery is at the forefront of foodtech: a value proposition natively build on local culture and habits and answering to key consumers expectations of simplification and quality. It also explains why the few brands that have been able to expand cross borders have become food giants, like Nestlé, Danone or Unilever.”

Johan Jorgensen from Sweden FoodTech believes that while of course there are cultural differences which are challenging across sectors, many European cities have common attitudes that will drive food tech adoption.

“If you look at places like London, Stockholm, Paris, Berlin, Barcelona etc. we see large, modern cities filled with (relatively speaking) healthy and sustainable people from the urban class. That fact will probably play a vital role going forward in the change process. The next-gen food system will be about urbanity and changing habits. Europe has a greater density of urban environments than most other places. I do also feel that awareness of the problem is higher in Europe than in the US heartlands. That makes for fertile ground.”

Corporate Inaction

While European corporates have been slow to act, like many in the US and other parts of the world too, Camphuis believes they’re waking up, particularly pointing to the high level of involvement of Danone in the recent Startupbootcamp Food Tech accelerator.

PitchBook also indicated corporate venture capital is growing as a portion of overall VC activity in the region, on track for another record year in 2018.

“What we see emerging is a convergence of interest between corporate and investors to help scale future food champions. Even if we don’t speak the same language, we share the same understanding of what makes good food and the need to help scale solutions that have the potential to deploy more globally,” says Camphius.

But even if food corporates remain slow, there’s opportunity for startups, Jorgensen argues.

“Many European food companies don’t get that the food system is broken and don’t understand the world data beyond their own and that provides fertile ground for foodtech-companies that can step in and exploit those weaknesses. We have a very big industrial food system in Europe that needs to change and entrepreneurs can help them do that. In fact, we need them to change…”

Key European FoodTech Successes

There have also been a few notable exits across the agrifood supply chain.

Upstream:

Pharmaq, a vaccine and health products for aquaculture, was acquired by Zoetis for $765 million in 2015.

DevGen, a Belgian hybrid seed company, was acquired by Syngenta for $522 million in 2013.

SCR Dairy, a cow monitoring tech company, was acquired by Allflex for $250 million in 2014.

Midstream:

Vitaflo, a UK provider of clinical nutritional products, was acquired by Nestle for $600 million in 2000.

Enzymotec,a global supplier of specialty lipid-based products and solutions, was acquired by Israel’s Frutarom for $270 million in 2017.

Downstream:

Delivery Hero IPO’d on the Frankfurt stock exchange at a valuation of $4.9 billion

HelloFresh IPO’d on the Frankfurt stock exchange at a valuation of $2bn in 2017.

Just Eat IPO’d on the London Stock Exchange at a valuation of $2.4 billion in 2014

Takeaway.com IPO’d on Euronext Amsterdam at a valuation of $1.1bn in 2016.

Bevyz, the drink dispensing technology, was acquired by Keurig Green Mountain in 2014.