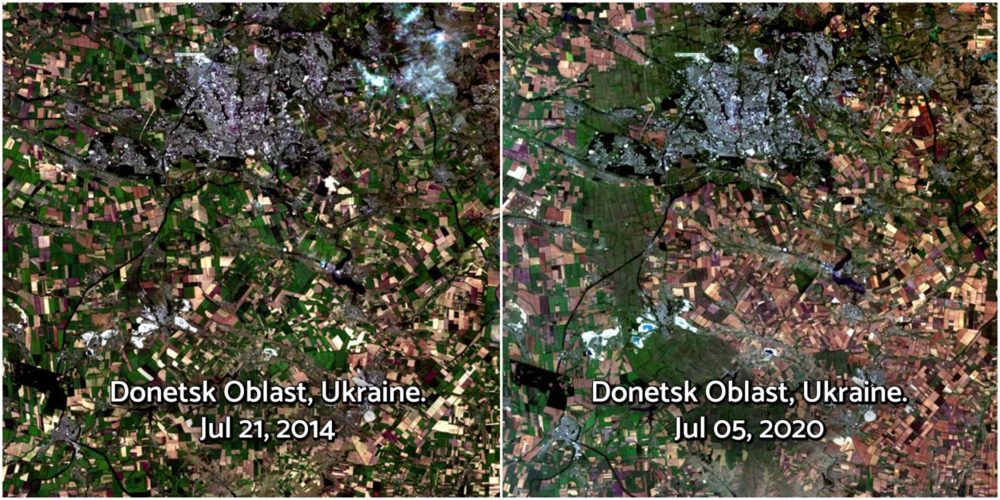

When Russia seized Crimea from Ukraine in early 2014, it marked the start of a harsh conflict that has beat on ever since. Initially, fighting was active and fierce, before freezing over into a tense and unresolved stalemate, albeit one with an intermittent staccato of military engagement.

Historically, the effects of these sorts of conflicts on agriculture have been devastating – yet hard to determine with much precision, owing to the inaccessibility of farmland within war zones. But they’re now becoming easier to measure with ever greater accuracy from a safer distance, thanks to new combinations of satellite imagery and artificial intelligence.

California’s EOS Crop Monitoring, for instance, has applied a machine learning algorithm that was created in cooperation with the Space Research Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

It reveals the amount of active croplands in the areas of eastern Ukraine that remain beyond government control. The research team told AFN it estimates the sown land there — that is, in the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics — stands at 1.3 million acres.

That’s a dramatic fall in agri-activity. In 2014, before the conflict started, there were 5 million acres on record in the Donetsk region alone. It is a significant hit in production for any country to take; even a world-leading grain producer like Ukraine, where total arable land still goes beyond 71 million acres (almost 17% of Europe’s agricultural land bank.)

Of that Ukrainian acreage, as a previous EOS project for the World Bank points out, satellite imagery from 2019 showed how there were almost 10.6 million acres of illegal farmland in Ukraine generating up to $3.8 billion in untaxed profits. To teach the algorithm and validate its accuracy, the scientists used the data gathered on the ground one year prior. They claim it’s 97% accurate.

According to EOS, its sowing maps based on satellite imagery can be used as a supplement to official statistics regarding the state of agriculture in any part of the world.

Burnt farms in Syria and Yemen

In Syria, extensive satellite agri-monitoring has been done since the outbreak of the civil war there in 2011. This has documented years of damage and destruction to lives, livelihoods, and critical supply chain infrastructure across the country. Spanish firm Deimos Imaging, for example, has been working on a project for monitoring farms and arable land in Syria and neighboring war-torn Iraq with Earth observation satellites Deimos-1 and Deimos-2.

In August, the conflict resolution nonprofit PAX conducted remote sensing analysis with imagery from the European Space Agency satellite Sentinel-2. The results put the extent of recent damage in sharp relief: roughly 437,000 acres of land were burned in Syria’s north-eastern Hasakah governorate between May 15 to July 25 this year, with 3,543 fires spotted over the same period.

This study is the first of what PAX calls its Environment and Conflict Alert series, a set of initiatives aimed at rapid environmental analysis in conflict-affected areas.

“Our aim is to use innovative research and earth observation to visualize the direct and long-term consequences of environmental damage and their impacts on lives and livelihoods of people in conflict-affected areas,” said PAX project leader Wim Zwijnenburg in a press release. “These issues deserve closer scrutiny in the wider analysis of armed conflict and in post-conflict reconstruction.”

Zwijnenburg himself has been actively tracking other conflicts too, including the civil war in Yemen. His wide-ranging research on Yemen, published by digital investigative journalism outlet Bellingcat, takes the dire damage to date farming in the country as a case study.

“We acquired Planet Labs imagery of the location and processed it to show vegetation with near-infrared bands,” he wrote, also mentioning extensive use of services like Google Earth Pro to aid his investigation. While this did map extensive damage and correlated with on the ground reports, he still saw the task of counting individual palm trees from space as a manual and therefore unfeasible one – something computer vision and higher resolution imagery could address soon, if not already.

Other key players providing similar services, other than international trade or food agencies, regulators, or insurers, includeWWF Sight and Global Surface Intelligence.