“When I came back to the farm, I knew that there was something wrong.”

Tom Cannon is referring to the time, 25 years ago, when he returned from school to help manage the family farm in Oklahoma. The farm, which had been in his family since the late 1800s, was mostly growing wheat at the time but also kept native grasslands for grazing cattle.

What struck him when he returned was the difference between the grasslands that had never been tilled or had any synthetic fertilizers on them, and the farmland that was meant to be the preferred land for growing crops.

“What I saw was native grass that had never been touched that was yielding a huge amount of biomass every year and was out-yielding what was considered to be the better land.”

The difference, he says, came down to the soil.

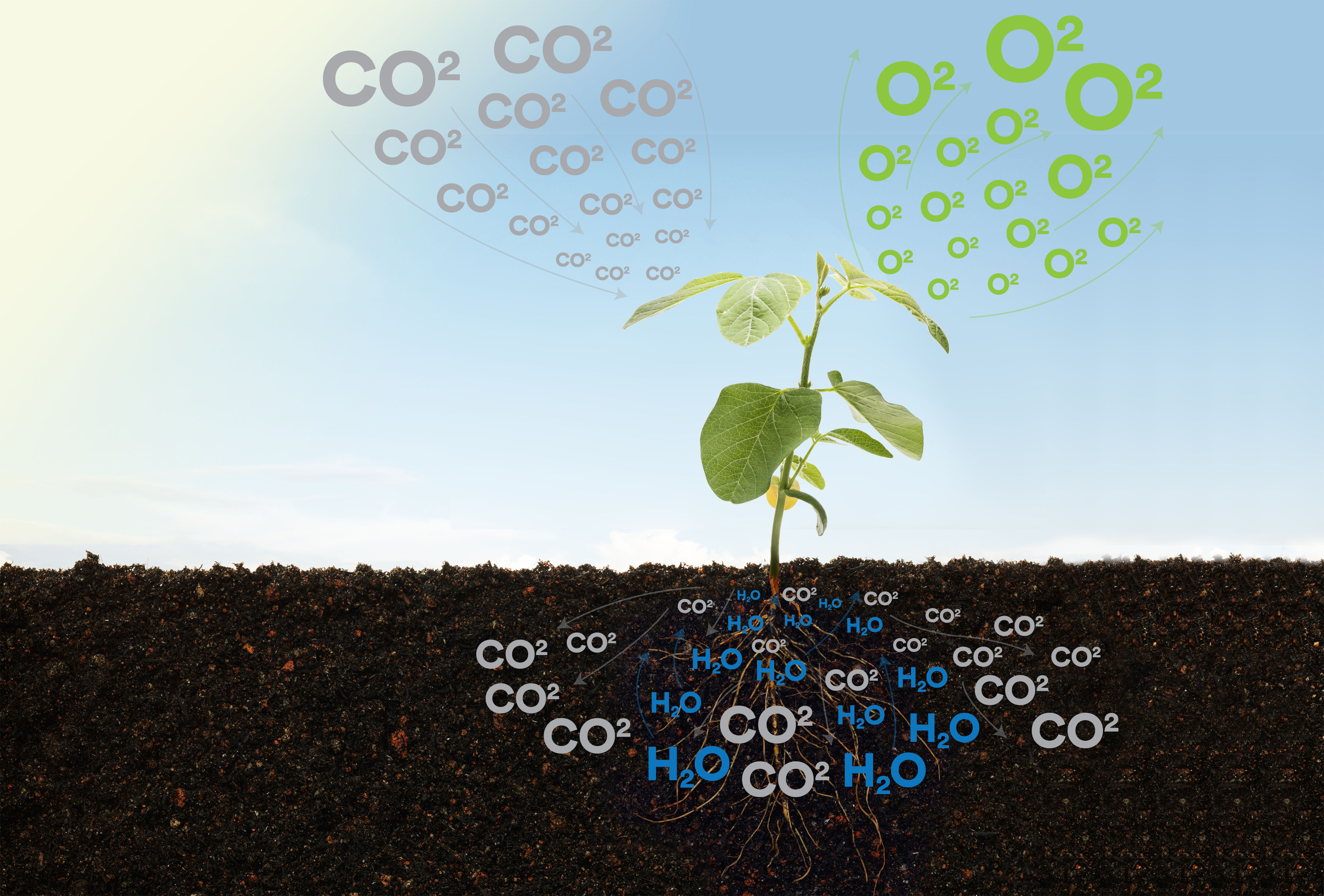

Some modern agricultural practices such as the use of synthetic pesticides or fertilizers and annual tilling result in the degradation of topsoil, the upper layer of soil containing the most nutrients, organic matter and microbes beneficial for plant growth. Abundant soil organic matter is also key to increased water retention and crop nutrient density–as well as storing carbon that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

As urgency to identify and adopt solutions to climate change builds, there’s a growing conversation globally about the role of healthy soils in combating the effects of increased greenhouse gas emissions–and what farmers like Cannon need to tap into the carbon sequestration potential of their land in a profitable and sustainable way.

Cannon never formally studied agricultural sciences. Instead, inspired by the abundance of the untouched grasslands, he began adopting what are now referred to as “regenerative” growing practices.

This involved selling all tillage equipment on the farm to ensure the soil was never disturbed, keeping the soil covered with multi-species cover crops, bringing livestock back onto the cropland, ceasing the use of any synthetic inputs, and rotating the crops he grew.

“That really hits on all the pillars of regenerative ag and I did that accidentally before anybody ever put these five pillars together. We just learned as we went,” he said, adding that no-one for miles around was doing the same. “Anytime there was a problem, and you talked to an extension agent or you talked to anybody within one of the large chemistry companies, they gave you a prescription of how to kill something,” he added. “I didn’t get the memo that I needed more fertilizer and more chemicals to make more yield.”

Step in Indigo Ag and The Terraton Challenge

Tired of the focus on using chemical solutions, Cannon has always been a keen trialist of biological and technological alternatives to improve soil fertility, reduce input cost and sustain his operation. As an Indigo Research Partner, Cannon has tested and adopted a variety of new products to support his regenerative approach, including Indigo’s own microbial treated seeds and a wealth of digital technologies. Now with The Terraton Challenge, Indigo’s open call to entrepreneurs across disciplines for innovations that can accelerate, quantify and reward carbon sequestration, Cannon is excited about the next round of technologies to trial.

“As a research partner with Indigo, I’m extremely excited that everything that Indigo has brought for us to test in the past has been legitimate with a real possibility of impacting my operation. I know that the people of Indigo are as good as it gets. They’re absolutely the top of the industry, and they’re not going to bring me anything to test unless it didn’t have a pretty good chance of having an impact.”

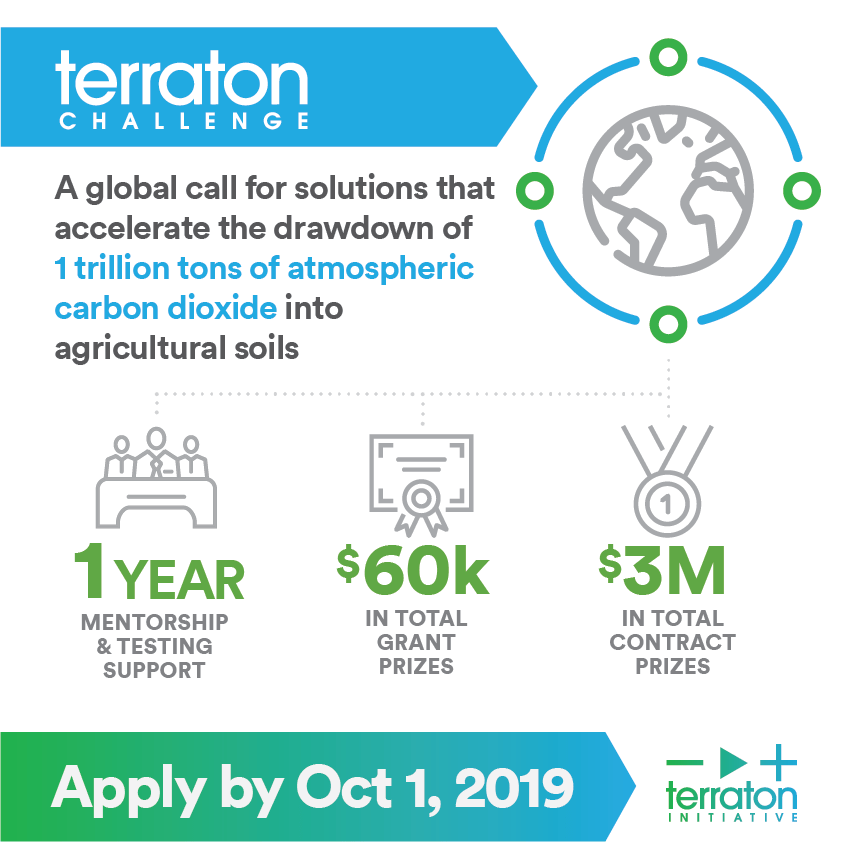

The Terraton Challenge is designed to further the goals of The Terraton Initiative–Indigo’s broader effort to capture one trillion tons of atmospheric carbon dioxide in the world’s agricultural soils–and will work closely with Indigo Research Partners like Cannon to vet, test and refine proposed solutions. Selected responses to the global call for ideas will be eligible to receive up to $60,000 in grants and $3 million in contracts, in addition to mentorship and real-world experimentation. The application period will remain open until October 1, 2019.

While Cannon noted existing opportunities to improve soil testing technology — “we need an accurate ability to prove, with repeatability, that we are making a positive change” — he also emphasized the importance of finding ways to reward growers for their role in drawing carbon down into their soils and of creating incentives that would accelerate an industry-level shift to regenerative practices.

These could be fintech tools with new carbon credit methodologies, or insurance products related to carbon sequestration. They could be novel accounting approaches for ecosystem services. Track and trace technologies that would enable proper identity preservation of products grown in a sustainable way, helping maintain their provenance to market them and potentially charge a premium, are also of interest.

While admitting that regenerative growing practices were gaining increasing attention, Cannon said that new technologies like the ones proposed through The Terraton Challenge will be essential in ensuring regenerative practices are widely accepted as a standard, not the exception.

“We have to be able to prove what regenerative producers already know. A great story goes a long way, but farmers want to see facts. I think that we have the possibility of being the heroes of climate change.”

To learn more about The Terraton Challenge and how to apply, please see here.

*This post was sponsored by Indigo Ag, an AgFunder Network Partner. Learn more here.*