Regenerative agriculture is having a moment. For long-time regen ag practitioners and proponents, this is probably jarring. But having written about regenerative agriculture for five years now, I’ve never seen such engagement or our stories about this ultra-sustainable method of farming perform so well.

Readers aren’t only engaging with the subject matter — the comments boards on these two stories are worth wading through — but the number of headlines about the strategy is also growing as more and more businesses realize the potential in what is, in fact, an age-old farming strategy.

There are many different definitions of regenerative agriculture, but broadly, it’s a set of “beyond sustainable” farming practices that aim to improve the land farmers use with a particular focus on soil health and with the potential to mitigate climate change through carbon sequestration.

In the last month, several major initiatives have launched to promote farmers’ transition to this style of farming. Just this week we report on a program in Montana to help ranchers transition to rotational grazing, two weeks’ ago dairy giant Danone launched a regenerative dairy project with some major players including Corteva, DSM, Yara, MSD Animal Health, and leading agriculture university Wageningen. Earlier in June Indigo Ag, the ambitious Boston-based startup launched the Terraton Initiative, with the intention of sequestering one trillion tons of carbon from the atmosphere through regenerative agriculture methods. Earlier this year, General Mills and Anheuser Busch also made commitments to regenerative agriculture.

It’s unclear at this point which initiatives are genuine, which will work, and which are merely trying to take advantage of the growth in consumer demand for sustainable-labeled food, but they certainly won’t be the last.

Investors are also getting in on the act.

Regenerative agriculture investing: Soil Wealth Report

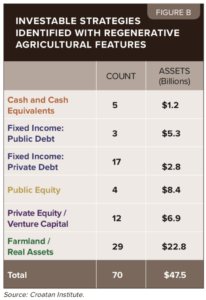

This week, a new report, cleverly called Soil Wealth, has come out detailing the level of investment in regenerative agriculture-related projects and the numbers are surprisingly high: there are some 70 investment strategies with assets under management of over $47.5 billion, and that’s just in the US.

Just to clarify, that amount includes all investments made by these firms, some of which were regenerative agriculture-focused. But the potential is there, so much so that a new conference dedicated to regenerative agriculture investing launches in September. And the asset class with the biggest focus on regenerative agriculture — farmland — is full of dedicated fund houses, purely focusing on it.

David LeZaks, one of the report’s authors from Delta Institute, is excited about the space opening up further.

“This is a great start, but we need a lot more investment activity to have a meaningful environmental impact,” he told AFN.

Why are investors looking at regenerative agriculture?

The increasing urgency of addressing climate change is a major factor, according to the report’s authors — Croatan Institute, Delta Institute and the Organic Agriculture Revitalization Strategy. Regenerative agriculture has the potential to sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it, not only halting the industry’s impact on the environment but reversing it.

The potential for outsized investment returns is another clear benefit.

The report’s authors estimate that some $700 billion of investment in regenerative agriculture in the next 30 years could not only return $10 trillion, a return on investment of 14.3 times but could mitigate nearly 170 Gigatons of CO2 emissions (GtCO2e). To put that into context, in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees centigrade, per the IPCC’s recommendation, we need to remove between 100 and 1,000 gigatons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, while we’re still emitting between 39 and 45 GtCO2 per year.

While various data point to the proven potential for certain agricultural practices to sequester carbon in the soil, there’s still some debate about how effective it could be in reversing climate change. Impossible Foods recently waded in to try and debunk the potential for rotational grazing, and members of the World Resources Institute are skeptical about the potential of the agriculture industry to effect widespread change in CO2 levels.

LeZaks said there’s a wealth of data to prove the carbon sequestration potential of regenerative agriculture.

“The uncertainty around carbon sequestration [through agricultural practices] is mainly focused around exactly where, how long, and what practices are followed, but where there is certainty is that we cannot continue to degrade agricultural land in the same way that we are today and there’s agreement in the direction we should be taking,” he told listeners on a call about the report today.

How are investors investing in regenerative agriculture?

The report, authored by the Croatan Institute, the Delta Institute and the Organic Agriculture Revitalization Strategy, highlights six different types of investment asset class investing in regenerative agriculture: cash, public debt, private debt, public equity, private equity and venture capital, and farmland/real assets.

The report, authored by the Croatan Institute, the Delta Institute and the Organic Agriculture Revitalization Strategy, highlights six different types of investment asset class investing in regenerative agriculture: cash, public debt, private debt, public equity, private equity and venture capital, and farmland/real assets.

While the public equity markets are increasingly focusing on ESG (environment, social and governance) metrics, just two funds were identified to pursue regenerative agriculture in some way: Calvert Investments and Trillium Asset Management. The fixed income and cash asset classes included a mix of local initiatives, banks, and investment management firms.

In venture capital, our main focus here at AFN, just five funds were identified as having made regenerative agriculture investments — Almanac Investments, Fifth Season Ventures, Fresh Source Capital, Renewal Funds, and S2G Ventures — although we believe there are more (AgFunder included with our investment in soil health startup Trace Genomics).

By comparison, farmland funds are the most prolific investors in the space, with 29 identified strategies, most of which attract large institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies, including TIAA-CREF’s own asset management firm Nuveen. Most of these funds purchase conventionally-farmed land and transition it to regenerative and organic, with the aim of increasing its value and revenues from more sustainably-labeled harvests. Practices adopted include cover cropping, no-till, crop rotations, reducing the use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers, and rotational grazing of livestock.

The report authors assess which asset classes, and specific types of investment vehicles, are most appropriate — or “regenerative ready” — with a leaning towards farmland, cash, and fixed income investment opportunities.

“We view farmland, cash, and fixed income as asset classes ripest for rapid development in part because bank financing remains the leading form of financing farms and businesses in rural communities,” it reads.

“Ultimately, though, our interest is in fostering diversified, total portfolio approaches to investing in regenerative agriculture across asset classes. As such, we also recommend continuing to work with

a secondary focus on equity investment, both public and private, and on private debt, where some of the greatest experimentation has already occurred, though at limited scale. Given the demonstrable social and environmental benefits associated with regenerative agriculture, we also strongly recommend greater blending of private investment with catalytic sources of capital from philanthropy and government, at multiple levels, using frameworks such as Integrated Capital that would expand the reach of regenerative agriculture.”