Editor’s Note: Spencer Maughan is a partner and Kieran Furlong is the entrepreneur in residence at agtech venture capital firm Finistere Ventures. Here they write about the growth of biological alternatives to synthetic, chemical crop protection products such as pesticides, and the potential for this segment to grow further.

Biological Crop Protection Attracting Interest

There has been a flurry of excitement surrounding biological crop protection over the last few years. Chemical pesticides are under increasing scrutiny from consumers and regulators, concerned about stress upon the environment and residuals in the food chain. Biopesticides can provide an alternative or supplement to these traditional chemical pesticides, as well as new modes of action to tackle increasingly resistant pests.

Early, high-profile venture capital exits such as AgraQuest, Becker-Underwood and Pasteuria, which returned hundreds of millions of dollars to investors, attracted the attention of entrepreneurs and investors, as well as the other large agrochemical companies.

So what is supporting these push-and-pull factors towards biologicals? Real advances in biological sciences. To name just a few: decreasing costs in the genetic sequencing of plant and soil microbiomes; advances in cost-effective, industrial-scale fermentation processes; and the emergence of novel gene-editing and RNAi technologies.

This has led to some very high profile start-ups—AgBiome, Benson Hill Biosystems, and Indigo, to name a few—raising large capital rounds from investors who anticipate similar high-value exits to those mentioned above. Yet when discussing biologicals with farmers, crop protection vendors, and industry veterans, skepticism still exists. The lack of major exits in the last two years certainly does not help.

So, are “biologicals” really the future of crop protection? We certainly think so.

Let’s explore some of the top reasons we’re betting on the next era of biologicals: number one is the high cost of bringing new chemicals to market. Bringing a new chemical crop protection product to market typically costs just under $300 million. In contrast, the proponents of biologicals claim to be able to bring new crop protection products to market for just $10 million-$15 million. Why are there such huge cost differences?

Regulatory Advantages for Biologicals

There are different regulatory requirements in the United States and Canada, where biopesticides, by definition, have lower hurdles to regulatory approval than synthetic chemical products. Some of the most costly health, safety and ecological trials that are required for chemicals (e.g. carcinogenicity and reproductive effects) are waived for biopesticides. The US EPA has explicitly set lower requirements for biologicals because of their “derived from natural materials” status. It remains to be seen if Europe and other jurisdictions will follow this lead.

Under-Investment in Biologicals Efficacy Trials

The agrochemical majors like Bayer/Monsanto, Dow/DuPont, ChemChina/Syngenta spend almost $50 million on field trials for each newly introduced chemical. The vast majority of this expenditure is focused on efficacy trials – different locations, different crops, different pests. If biological products are being brought to market for $10 million in total, they are not coming anywhere close to this level of “in-the-field” testing. Farmers hold biologicals to the same standard as chemical products, but biologicals have not been tested in field trials to nearly the same extent. So while there are financial benefits, this may be at the root of the skepticism often heard about biologicals—“They work sometimes, but not always”.

New Chemicals Often Bear the Burden of Failed Investments

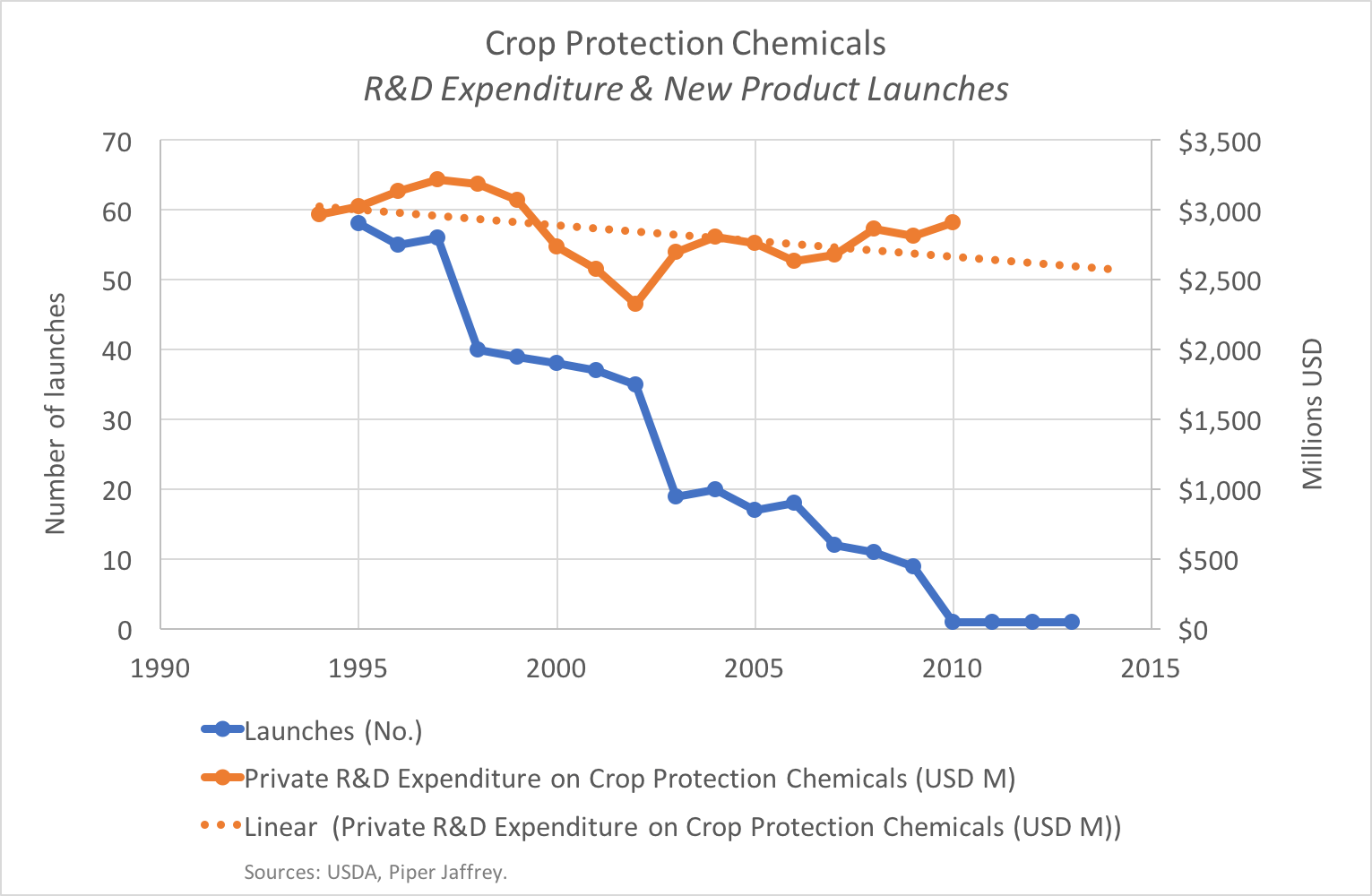

The $300 million versus $10 million comparison is hardly “apples to apples.” There is undoubtedly some numerator/denominator conflation for a new chemical as a portion of the expenditure rolled into that $300 million figure was not directly spent on that particular new product. Private crop protection R&D expenditure has remained roughly flat over past decades, yet the number of new products launched has fallen dramatically (Figure 1). The number of new leads investigated per single new product launched has soared and innovators are now researching over 100,000 leads before finding a new product. The huge fixed and operating costs of crop protection R&D are being allocated to fewer and fewer products, which is driving up the apparent cost per new product.

The $300 million figure for a new chemical product is essentially the cost of a portfolio of development projects from which only one emerges for sale. In contrast, the $10 million-$15 million estimate for new biologicals is the cost of just one project; failed or halted products (or even other startups) are not wrapped into that number.

How to Manage the Cost of Discovery and Efficacy Testing

You might ask why the hit rate for chemicals is so low, and why field trials take so long and are so costly? These are indeed the right questions to be asking. The crop protection majors screen hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of distinct compounds in their search for new tools for the farmer. However, the diversity of possible molecules – whether produced synthetically or via biological routes – is practically infinite.

Are the scientist-prospectors drilling the same wells with the same tools? If so, this opens up other potential avenues for entrepreneurs and investors. That is why we are looking for investment opportunities in new discovery platforms, new screening tools and new libraries – as well as new “actives” themselves, be they of biological or synthetic-chemical origin. The field of biologicals is indeed a new “well” to be tapped, but new technologies may create new wells in traditional chemistry too.

There is also huge opportunity for technology to play a role in reducing the number of field trials needed. Utilizing bio-informatics, artificial intelligence, and increased knowledge of the plant and soil microbiomes, can potentially allow more work to be done in silica. For now, though, it is clear that there will be a continued need for extensive, expensive field testing of new crop protection products. As such, it is time to consider an alternative model for investing in the development of novel biological crop protection products. It will probably take longer and cost more to move such products from initial lead to a robust commercial product than the typical venture capital investment cycle allows.

However, venture capital has an incredibly important role to play in crop protection innovation – the early, high-risk stage of development. Rather than waiting to exit on the basis of commercial sales, VCs should seek to pass the baton to the agrochemical majors (or other acquirers) at an intermediate point where the high-risk product development activity has been significantly completed, but before the capital-intensive stages of extensive field trials and widespread market entry. Such a staged model has become the norm in the pharmaceutical industry and – while there are many differences – it is worth looking to that model for ag lessons.