Editor’s Note: Dr. Jim Budzynski is the managing principal of MacroGain Partners, a consulting and investment firm focused on helping agricultural firms develop business strategies and find capital to prepare for the future. He can be reached by email here. Here he writes about the entrance of new investors into the agriculture asset class and the impact that has on the growth of the market.

A friend asked me the other day whether I thought all the outside investment in agriculture had been a good thing for the industry. I have spent many years working with non-ag investors of all stripes who are interested in investing in agriculture. While a number of these investors have been great assets to our industry, many others have been a net negative for agriculture.

Why Ag? Financialization and Asset Bubbles

The first thing to understand, and this has nothing to do with agriculture, is that we are in the late stages of a 30-year run of destructive monetary policy. Since the late 1980s, the US Federal Reserve has pursued a policy of trying to drive economic growth through manipulation of the supply and price of money with zero interest rates and by printing money. Their basic premise was that we just don’t have enough debt, and if we make money cheap enough folks will borrow and fuel a perpetual economic expansion. Well, they have clearly fixed that “not enough debt” problem, as we now have record levels of debt at the corporate, personal, and government levels. It’s shocking how both economists and consumers think growth fueled by borrowing money is a sustainable strategy. To paraphrase President Trump, this is fake growth.

This policy has resulted in a massive asset price bubble in every part of the economy – homes, commercial real estate, stocks, and bonds. Guess who owns most of these assets? The richest 10% of the population. But aside from the highly negative effect of this monetary policy in increasing income inequality and punishing savers, the most pronounced effect has been the “financialization” of the US economy. Have you noticed those TV ads for new cars and trucks don’t mention the price, only the monthly payment? Homebuilders are now starting to do the same thing. Our entire economy, and lives, are being reduced to a portfolio of cash flow streams, being sliced and diced and endlessly resold to investors desperately searching for yield. This is financialization, and it has worked its way over 30 years into every nook and cranny of our lives and economy – and it will end badly.

So what does this have to do with ag? Well, ag was traditionally a little too complex and cyclical for outside investors. But after 30 years, that ocean of cheap/free money is finally making its way to our shores here in agriculture. Congratulations.

The huge ethanol bubble that began in 2004-2006, which resulted in – temporarily — sky-high corn prices, fueled the rush of capital into “the next big thing,” which at this point was agriculture. What did most Wall Street investors do when ethanol crashed? They left to find “the next big thing”. The reality is that hot money only loves you when you’re hot.

Four Flavors of Outside Investors

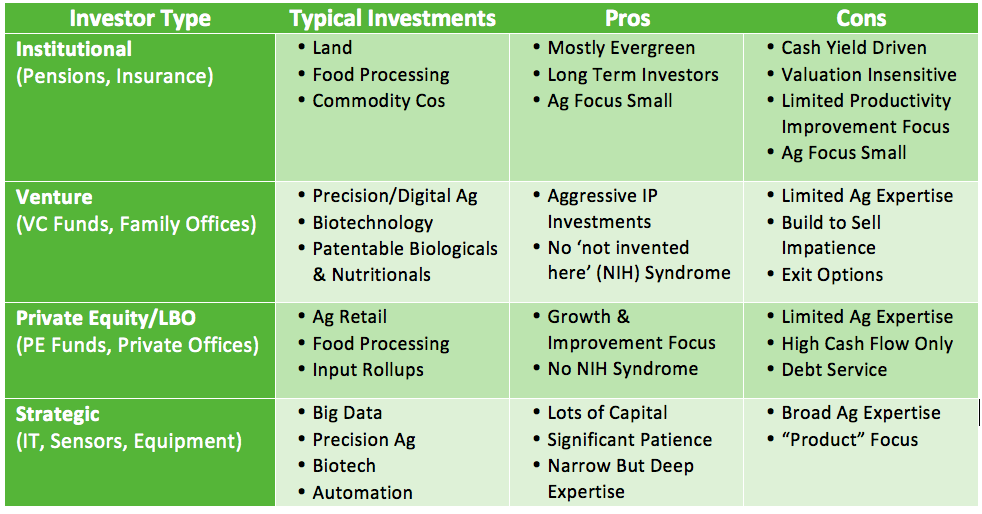

While there are many kinds of outside investors, I think of them in four broad categories (see Table 1):

1. Institutional Investors. Many pension and insurance companies were the first outsiders to invest in ag, and have traditionally focused on farmland investments, although more recently they have also begun to invest in operating businesses, especially in commodity or food processing. Institutions have the advantage of being very long-term investors with evergreen time frames.

Farmland investors derive their total return from two buckets – cash yield on assets (cash rent) and farmland appreciation. Over the past ten years, rapid appreciation of farmland — in part caused by all these investors — caused declining cash returns as investors accepted capitalization rates (yields) as low as long term bond rates. But investors ignored this declining yield because their portfolio was steadily appreciating in value as farmland prices increased. In the past two years, farmland values have started declining and investors increasingly realize that their meager yields may start to increase, but at the price of huge write-downs in the value of their portfolio.

Ag also tends to be a small portion of their overall portfolio, which can be good or bad; patient when ag is bumpy — but everything else is great — and impatient when the core investment portfolio becomes choppier — think 2009.

2. Venture Investors. Many funds are focused on venture investing in agriculture, and this sector has been growing rapidly through investments in precision ag, biotechnology, and patentable inputs (nutritional or biological products). Most venture funds are limited life funds and need to invest, develop, and sell within 10 years — obviously that’s less if the fund is 4-5 years old before it invests. This time pressure makes them aggressive in developing intellectual property (IP) and willing to try many approaches. The downside is a lack of ag expertise and the impatience that comes from building to sell. Most significantly, exit options are limited by the recent consolidation of the agrochemical majors (Bayer/Monsanto, DowDuPont, ChemChina/Syngenta) and the lack of a robust ag IPO market. Simply put, if 10 companies in the same vertical all aspire to exit to Monsanto, the best one or maybe two may get bought and the others will die on the vine, which tends to make exits a binary outcome — either euphoria or depression.

3. Private Equity Investors. Although technically venture capital is a flavor of private equity, the term in common usage refers to funds doing leveraged buy-outs (LBOs), usually through 10 year funds as well. They have focused on ag retail, food processing, and input rollups (fertilizer, seeds, chemicals). Like venture funds, this results in an aggressive focus on growth and development of the company, and a similar challenge with a lack of historical ag expertise. Their downside is the “L” in LBO, as debt-financed investments are tougher in low margin or highly cyclical sectors. In many cases, the reliable generators of high cash flow have already been scooped up in the huge consolidation that occurred from the 1980s to 2000s.

4. Strategics. Companies outside agriculture like Google (big data) or Bosch (automation) represent the newest group of outside investors, which plan to leverage their core skills and expertise in the ag vertical, particularly as the next wave of transformation occurs in agriculture. This type of investor has the capital and patience to solve big challenges. Their biggest weaknesses are a lack of focused ag expertise or a “product” focus, which means they may settle for leveraging existing industrial or consumer offerings into “ag-focused flavors” instead of truly creating great (new) things in agriculture.

Table 1: Four Types of Outside Ag Investors

Outside Ag Investors – Blessing or Curse?

On balance, outside investors will be good for agriculture. Just think where we would be if the Fed and the ethanol bubble hadn’t unleashed this investment frenzy – probably plodding along with a small fraction of the investment. That said, in my opinion the ideal investor for ag hasn’t come along yet. When they do, they will have a 10-year investing horizon, no need for debt leverage or 4% cash yields, not a “build to sell” model, and a focus on sustainable and novel value creation as opposed to product extensions. If you’re out there, and just need additional ag expertise, sign me up!