Vertical farming, the practice of growing produce indoors, under controlled conditions and in an urban setting, is still a relatively small market compared to other parts of the agtech sector.

In 2015, startups producing technologies in and around the “indoor agriculture” space, raised just over $107 million in funding, according to AgFunder’s Investing Report. That was just over 2% of $4.6 billion total investing in agtech during the year.

There are currently around 230 vertical farms globally, the majority of which are based in Japan. But the segment is gathering pace in other markets like the US where the existing produce industry that’s centered around Californian production which has large structural problems, mainly around water resources, and a large carbon footprint associated with it.

Keen to transition vertical farming from a movement into an efficient industry, two enthusiasts, Max Loessl and Henry Gordon-Smith, conceived of and launched the Association for Vertical Farming (AVF) in 2013.

“We saw more and more vertical farms pop up around the world behind closed doors, unaware of new developments, and making the same mistakes over and over again,” said Loessl. “So we saw the need for an industry association to bring the sector together and provide companies, universities, experts and newcomers a platform to interact, exchange best practices, and collaboratively transition this movement into an industry.”

The AVF launched under the guidance of Dr. Dickson Despommier, who coined the term vertical farming in 2008. Loessl’s mother, Christine Zimmermann Loessl, who has extensive experience running and building non-profits, also helped co-found the non-profit and acts as Chairwoman.

With nearly three years and an industry event in Beijing last year under its belt, the AVF is now keen to move the conversation on.

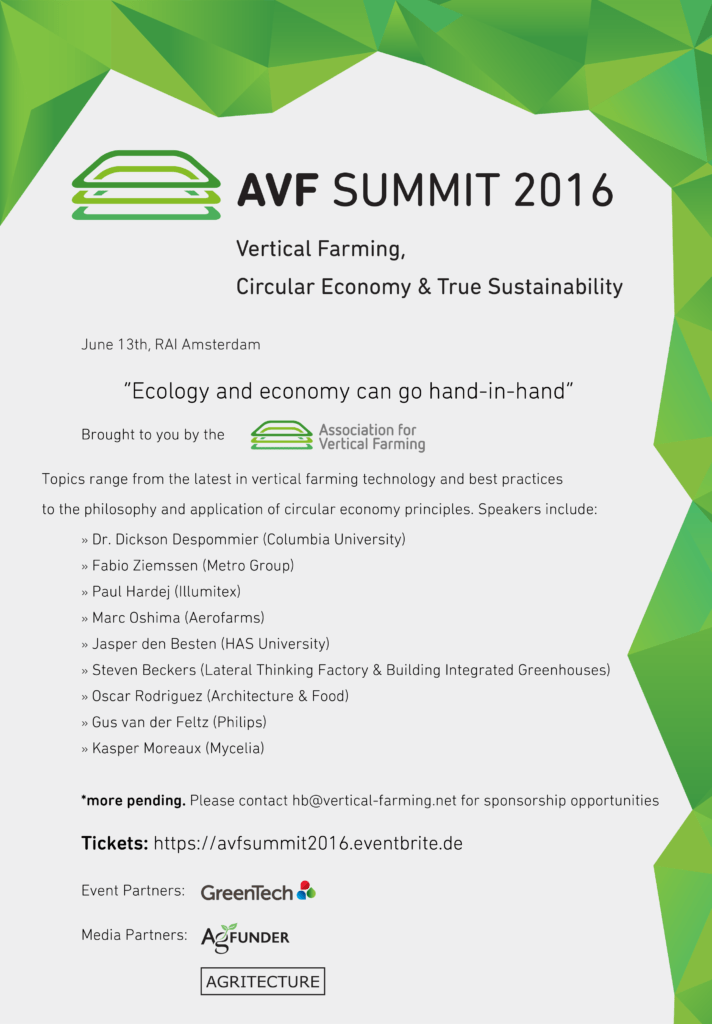

This year the association will hold its second annual summit in Amsterdam on June 13 at the RAI convention center the day before GreenTech, one of the largest horticultural exhibitions in the world. A lot of AVF Members will also be exhibiting technology in the Vertical Farming Pavilion at GreenTech).

The theme of the AVF Summit this year reflects the journey the vertical farming industry is taking, or the journey Gordon-Smith and Loessl hope it will take.

“Last year the summit was about taking food production to new heights, but we now need to move beyond just promoting vertical farming and how it works, but to start asking deeper questions about how they operate and their impact on the greater urban ecosystem,” said Gordon-Smith.

The growth in the number of vertical farms globally informed the decision to make this year’s event about the concept of the circular economy and true sustainability; how indoor farming can fit into the different flows of a city such as energy, water, waste and food chains. It will also touch on aquaponics, insect and mushroom cultivation and how these can fit into the vertical farms of the future.

“We engaged Columbia university to do a sustainability study on what makes one city more sustainable over another, and this was an exciting transition for AVF,” said Gordon-Smith. “While of course we continue to promote vertical farming, we are now spending resources to talk about what vertical farming means in the context of future cities.”

“We want to create a roadmap for fitting vertical farming into city planning and the development or urban areas,” added Loessl.

Moving the vertical farming conversation on

Oscar Rodriguez, an architect and a speaker at the AVF Summit this year, became a proponent of urban farming after he became sick of architecture paying little more than lip service to addressing climate change. Of the mega-trends he researched, food represented a very architectural intersection of so many of these concerns and had historically been a key driver of city development.

Until the advent of coal and railways, a close and accessible food supply had been a key driver and design parameter for cities. With coal, the steam engine and then oil and the combustion engine, people realized you could grow food further away from consumers and the relationship started to break down. Meanwhile, the nutrient feedback cycle which had kept soils fertile with horse manure and human waste, was replaced with sewers and landfill, meaning that our capacity to grow food into the long term declined as arable land gradually lost its fertility.

“That was one of the main drivers of the Green Revolution in the 1950s; we discovered that natural gas derived, nitrogen-based chemicals could replace that fertility and protect large monocultures. These chemicals were alien to natural processes and effectively acted like steroids. It took decades before we understood their long term effects to soils and our health,” Rodriguez told AgFunderNews.

Cities have a lot of excess capacity and space, particularly on vacant or under-used rooftops, empty buildings or redundant forms of infrastructure. They’re also abundant in resources like water, labor, energy, and heat, a lot of which is wasted.

Tapping waste heat and Co2 from a host building could substitute the need for gas heaters in a rooftop greenhouse operation, for example. Rooftop greenhouses also help insulate the host building in the winter and offer evaporative cooling in the summer, reducing building operational costs.

“The question for me as an architect is how can I integrate it all together into a system that still delivers the host building’s needs, but can offer hyperlocal food production as well? How do we eliminate the whole idea of waste and feed outputs from the host as inputs into a horticultural operation within the same building? On top of all of this, how does it fulfill a viable business model and, wherever appropriate, deliver on a social mandate?”

This is Circular Economy thinking and Rodriguez looks to the natural world to mimic processes and systems that connect waste streams to input streams. “Vertical farming is largely about packaging natural processes and putting it to work for our economic interests,” he said.

“Circular economy thinking drives services, practices and industries to talk to each other that haven’t before,” said Rodriguez. “We almost have to do this by necessity if you look at the long term macroeconomic indicators around oil, water, phosphates, climate and demographics,” he said. “When oil prices rose suddenly in 1973, for example, one of the most dangerous ramifications was its effect on food prices. In 2008, high food prices directly contributed to the discontent that sparked riots leading to the Arab Spring. Phosphates are scheduled to run out in 20-30 years. Shifting hydrological cycles and Climate Change is already having a hugely destabilising effect. If our relationship to our food supply is not addressed while we have relative stability, there may be serious trouble ahead.”

The US is better positioned to absorb urban farms than other countries like the UK, Rodriguez argues, because there are large structural problems with the US fruit and vegetable market, not least water resource constraints. In the UK, however, there is a challenge over the costs of deploying several urban farms as each building brings different issues. And therefore produce might not be competitive with the traditional industry.

Are you interested in hearing more about how vertical farming can promote a circular economy? Find out more about the AVF Summit 2016 here.