Editor’s Note: John Corbett is founder and CEO of aWhere, a weather data analytics company. aWhere operates what it describes at “the world’s largest network of detailed daily weather delivering accurate, localized and in-time observed weather to farmers and the agri-food sector with 1.9 million virtual weather stations covering the world from 60°N–60°S.”

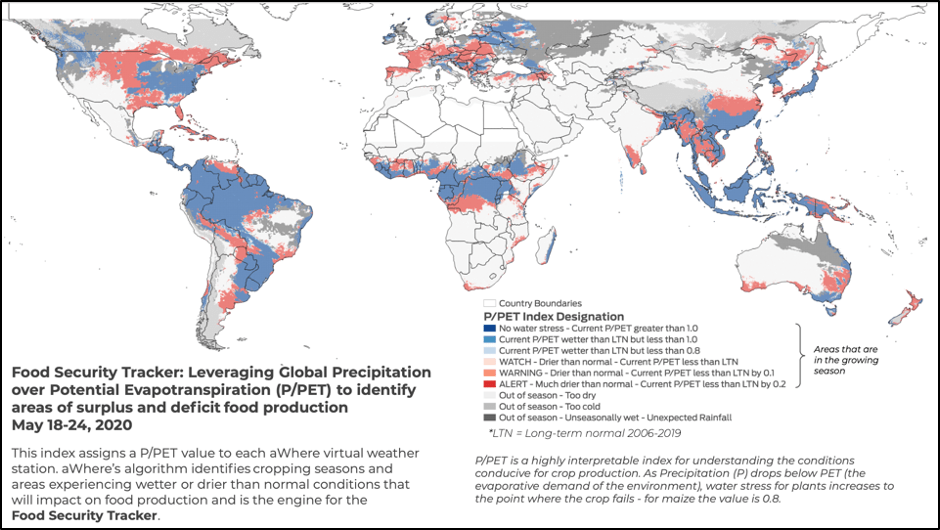

Relevant to current times, its Food Security Tracker provides visibility to anomalies in the weather during the growing season that could impact crop yields and farmer ability to adapt in time. Here he aims to illustrate some of these changes to global weather patterns and how weather data access can empower farmers and our food system to become more resilient, even during the Covid-19 epidemic.

Agriculture is a weather-driven sector.

Increasing weather variability due to a warmer atmosphere, coupled with Covid-19 supply chain disruptions and trade restrictions, are driving up food prices and increasing food insecurity in 2020. Many countries that traditionally depend on food imports are now facing shortages of key staples as trade and transport restrictions, compromise domestic food supplies, triggered by Covid-19 responses.

One of our greatest risks for the future is that we have underestimated the extent of weather extremes: storms are more intense over a shorter period and droughts are deeper and more damaging. Farmers need between 75-150 days of ‘normal’ weather to harvest a crop. Disruption in the timing or intensity of rains, for example, can have a devastating impact on crop production, farmer income, and food security.

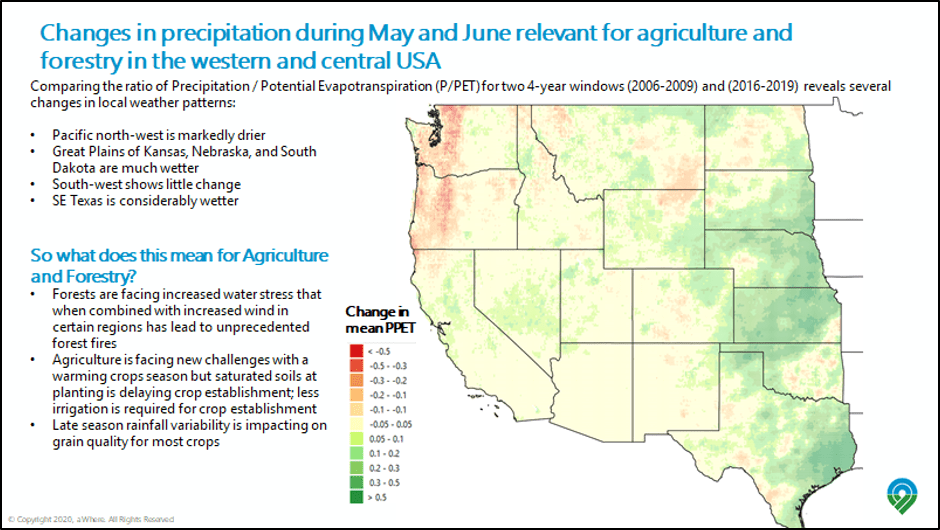

Increased weather variability during the past decade poses an additional risk to food production. As weather patterns change, farmers may need to switch out crops more sensitive to weather variability for alternative crops or invest in improved water management practices to keep pace with domestic demand.

Developed market consumers might even be starting to draw a more direct line between the weather and their own food supply as increasing numbers have started to grow food at home in so-called ‘victory gardens’ due to concerns about food shortages in the wake of the pandemic.

As the weather changes, weather-driven insights become critical information to inform food producers – from large-scale commercial farms to backyard gardens. Backyard gardeners are asking what crops are adapted to their climate, when to plant, and how to care for their plants. These are the same questions smallholder farmers in emerging economies ask yet have limited access to timely data and information. With social distancing and travel limits, smallholders that relied on their frequent trips to the market or visits from extension agents for intel could be left with even less information than before.

Weather data create 10%-30% productivity increase

Of course we’d say this, but real-time recommendations based on actual observed weather data will become increasingly important to empower farmers globally to adapt to weather variability and increase their farm productivity. And there are data to prove it. According to trials Microsoft undertook with ICRISAT in India a few years ago, admittedly using our data, weather information increased productivity by 10%-30%. It can also increase resilience to climate change, especially in dryland rainfed ecologies in emerging markets.

Using weather data to combat specific problems

Observed weather in a grid is a convenient way to take crop modeling to scale to enable farmers (and input providers and supply chain managers) to get ahead of pest and disease threats, reduce risk, and increase operational efficiency to maximize yields. One example is the use of weather data to get ahead of fungal diseases that produce mycotoxins: Aspergillus ear rots in corn produce a carcinogen called aflatoxin; modeling areas at high risk enables targeted sampling of grains to ensure food safety. We are now exploring how a global weather grid may even support modeling of Covid-19 as we enter the flu season of 2020.

Trends in growing season behavior – hotter, wetter, drier, colder – provide valuable insights into how best to adapt to shifts in weather patterns. For example, the map below of Zambia shows where to invest in watershed management and augmentative irrigation, which would enable farmers to adapt to drier growing conditions based on trend analysis. In more extreme cases, farmers will need to shift to drought-tolerant crops like sorghum and millets that are more resilient than corn. Shifting to new crops has implications for the diet preferences of those impacted and increases the need for agronomic information on how to grow the new crop. Small-holder farmers who increasingly have access to a cell phone can now access weather information and agronomic recommendations driven by weather data to inform what crop to plant, when to plant and how to respond to ‘anomalous weather.’ Text messages that offer these actionable insights can cover the final mile that traditional extensions systems have not been able to sustain at a large scale.

Access to weather data can also bring an impressive Return on Investment (ROI). It costs approximately $5.00 (depending on the country and provider) to send 20 text messages to a farmer during a growing season; this is the cost for the message, the agronomic modeling, and the weather data that drives the models. If a one-hectare farm produces $700 in a growing season (a conservative figure for most emerging markets), a 10% productivity increase due to weather information provides a return of $70 or more for a 1,400% return on the $5.00 investment in SMS weather services.

As the full impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on our world becomes clear, the need to invest in modernizing our farming industry and food supply chain overall is increasingly obvious. One response to Covid-19 is border closures; the agricultural response is to grow more diverse, with new crops within each country. In-time information becomes even more critical as farmers deal with weather variability and new crop demands. Moreover, while for some markets, agricultural innovation might involve introducing more hi-tech tools such as robotics on the farm to increase efficiencies, for many developing economies, productivity is dependent on human labor. In this situation, just increased access to information such as weather will make a huge difference. An inadvertent impact of Covid-19 might be its catalytic stimulus to growing technological investments in agriculture.