Editor’s Note: Henry Gordon-Smith is CEO at Agritecture, an urban farming consultancy and software platform based in New York, US. Here he writes about extensive research done by his team into labor shortages in the Middle East. The views expressed in this guest commentary are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of AFN.

No farmers. No food. No future. That is the saying that reminds us to value not just where our food comes from, but the farmers that grow it for us. While much of the agtech discussions these days focus on investment, markets, technology, and policy, the topic of skilled labor for the future of food is less explored. Let’s investigate how a gap in skilled labor could slow the growth of food security in one of the world’s most rapidly developing AgTech markets.

Imagine you invest in a huge shiny new high-tech greenhouse in an emerging market only to find that there is insufficient local talent to operate all your fancy technology. You spend more and more time on recruiting, training, and desperately trying to retain the talent you have. This challenge is becoming an increasingly critical issue in the Middle East where a skilled labor gap for climate-smart agriculture is on the horizon.

Definition of skilled labor:

“A skilled worker is any worker who has special skill, training, knowledge which they can then apply to their work. A skilled worker may have attended a college, university or technical school. Alternatively, a skilled worker may have learned their skills on the job.”

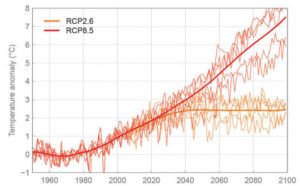

We already know that climate change poses a considerable risk to water efficiency, temperature gradient and food security across the globe. Rising temperatures, water scarcity, floods, and other extreme weather conditions are occurring in both higher intensities and frequencies. Some regions are on the edge of this climate crisis, threatening key resources harder and faster.

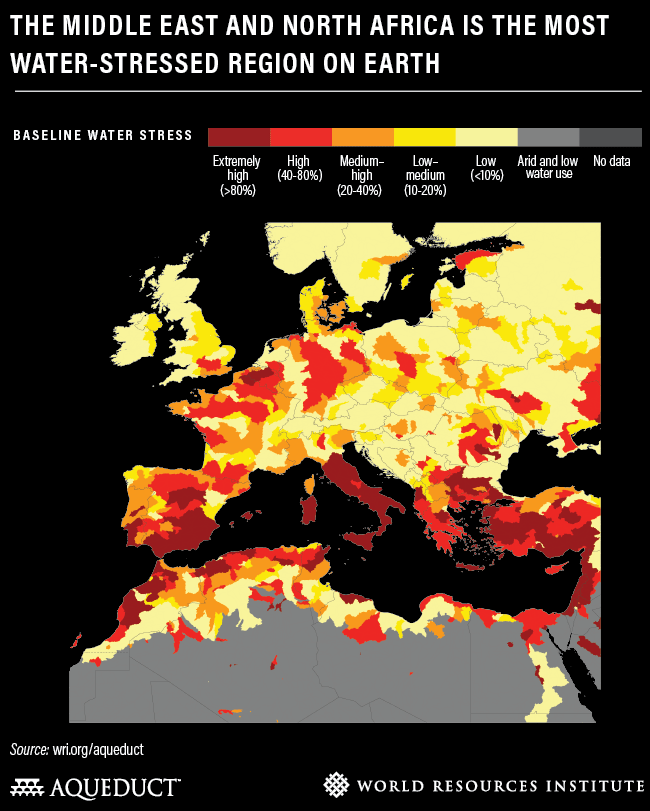

According to the World Resources Institute, there are 17 countries globally suffering from “extremely high water stress”, and 12 are located in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region due to their desert climate and growing water demand. This makes the MENA region highly vulnerable to climate change and a region of rapidly growing interest in Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) that can withstand the water stress and high temperatures now and in the future.

One proposed solution that is getting a lot of attention in the Middle East is Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA), which has the objective of giving this largely desert region resilience against future challenges. In fact, millions has already been invested into this sector in the Middle East and bold plans for food security have been outlined by governments in UAE, KSA, and Egypt to name a few. At COP27, CSA was pushed by public and private leaders as worthy of further investment as the UAE-US led AIM4Climate program doubled its investments to $8bn.

What is climate-smart agriculture?

Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) is a term popularized by UN-related organizations to encapsulate the efficiency and adaptability needed in agriculture. CSA is an integrated approach to managing landscapes—cropland, livestock, forests and fisheries—that addresses the interlinked challenges of food security and accelerating climate change. CSA aims to simultaneously achieve three outcomes:

- Increased productivity

- Enhanced resilience

- Reduced emissions

When it comes to CSA in the region, Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) can play a significant role. It is growing rapidly with the world’s largest vertical farm constructed in Dubai and some of the largest greenhouses being built in Egypt. Despite all of these policies and investments, a recent study, funded by IOM and led by Agritecture found that there is a looming skills gap for CEA in both UAE and Egypt.

Research partnership with international migration group

Agritecture partnered with the International Organization of Migration and Hydro Farms, a regional leader in Agri-Tech solutions from Cairo, to research and analyze the current problems of CSA in the region to predict future needs and the role skilled migrant labor could play so the industry can run efficiently and effectively.

The approach we took for the assessment was focused on getting the maximum information from key private sector stakeholders and focused on desktop research, an operator survey, and stakeholder interviews. The major topic of this cooperation was to research, identify and better understand labor gaps related to CSA skills in the region from industry experts and how a Skills Mobility Partnership (SMP) can benefit these countries and equip agricultural workers with essential skills for the industry and other everyday benefits that can be applied in both countries.

Desktop Research

First, the team looked at publicly-available data centered around identifying all major hydroponic greenhouse and other CSA operators in the regions. Research was also conducted to better understand the greenhouse and hydroponic market growth and market sizes, as well as estimates of the skilled labor growth needed for CSA operations over the next 5 years. The team also sought to identify key private sector stakeholders and existing programs and actors in CSA in the region.

The initial findings showed that there are few programs and plans to address systematically the rising demand for skilled labor in CSA across Egypt and the UAE. Skilled labor is a segment of the workforce that has specialized know-how, training, and experience to carry out more complex physical, or mental tasks than routine job functions. Our desktop research found that there are simply not nearly enough training programs, recruiting solutions, and migration programs to fill the demand that would exist when the region’s bold, and necessary food security targets are to be achieved. We needed to dig deeper and speak with the operators on the ground to understand if this was something that they were concerned about too.

Survey

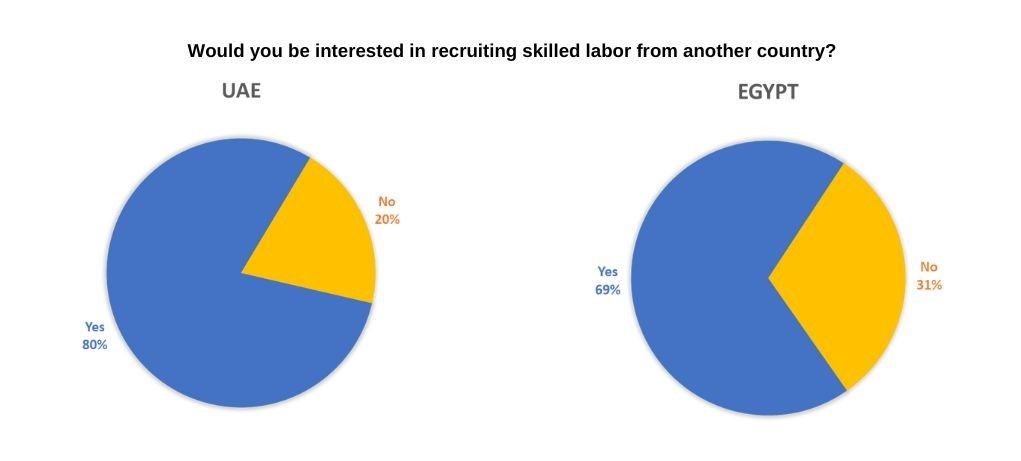

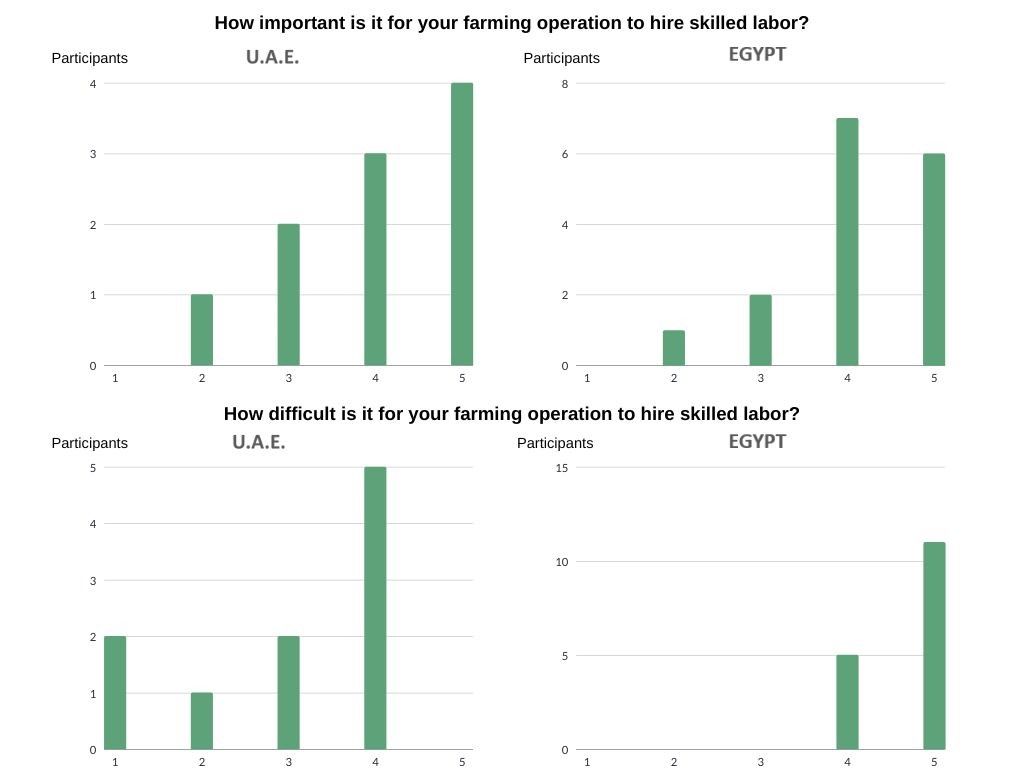

Second, the team created a survey and sent it to 26 CSA operations identified from the desktop research in the UAE & Egypt. The purpose of the survey was to better understand gaps in skilled labor amongst CSA operators. The beginning survey questions ranged from defining the operation type (from low-medium tech hydroponic greenhouses to high-tech vertical farms and smart irrigation for open field agriculture), to current number of laborers and number of skilled laborers. The questions then focused more on skilled labor, presenting prompts such as anticipated number of skilled laborers to be hired in the next 1, 2, and 5 years, importance of hiring skilled labor, difficulty in hiring skilled labor, interest in recruiting domestic and / or foreign labor, and willingness to pay more for certified labor.

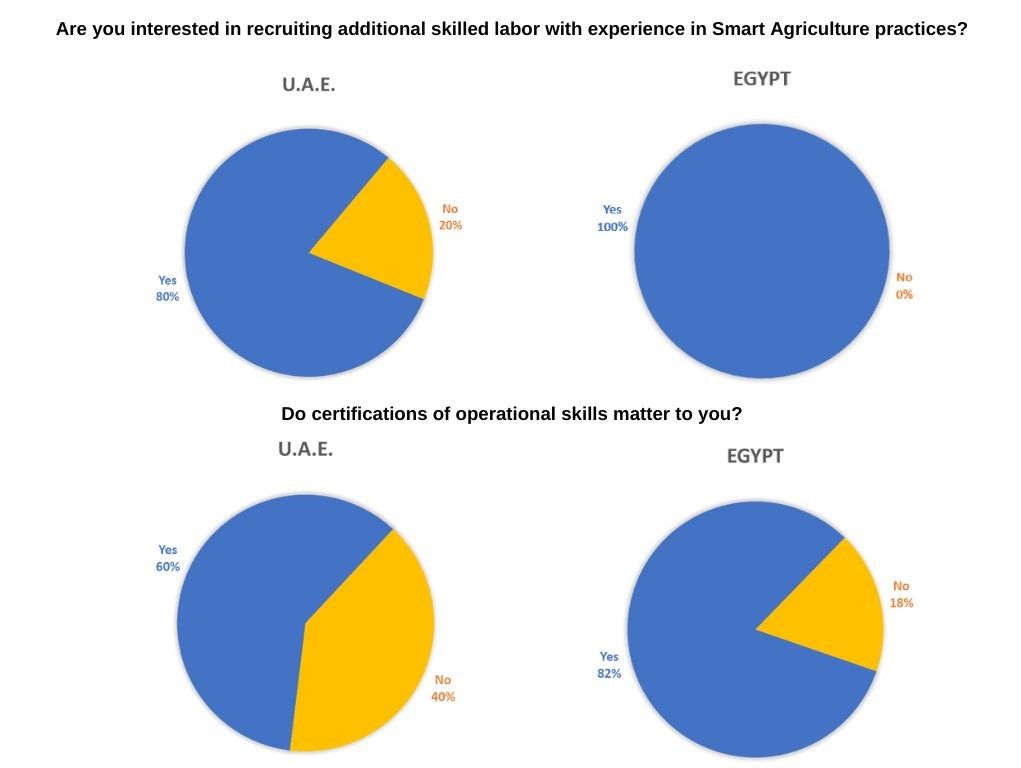

Most of the operators both in UAE and Egypt have stated that it is “important” to “very important” for their company to hire skilled labor, and at the same time is “difficult” to “very difficult” to recruit them. The survey found that most of the operators are interested in recruiting additional skilled labor with relevant experience in smart agriculture similar to their operations and ideally be certified in key relevant skills.

Individual and group interviews

A webinar was conducted to share insights from desktop research, build trust with CSA operators, and hear their comments and questions on the initial survey results. The webinar included CSA operators from both countries who shared their concerns around skilled labor and other topics of concern to them. Some of the operators shared concerns that funding and project development was more important to them at this stage than skilled labor while others emphasized concerns about the costs of training skilled labor in their operations only to lose them to competitors. Overall, the webinar confirmed there are a range of challenges for CSA operators and skilled labor gaps are one of them but not always the most important.

Moving forward next steps

Based on initial findings from this project, it is clear that CSA is a growing sector in the MENA region given all the attention it gets from stakeholders, projects, and investments. Thus, more CSA operations will be built in the future, and there is a high likelihood of a major skilled labor gap for operating these types of facilities. In order to reach its full potential, CSA must be applied alongside strategic practices, such as the development of training programs, thus providing these CSA operations with a fully skilled workforce.

In Egypt, efforts to boost agricultural production so far have focused on investment in the infrastructure through the largest greenhouse project in the Middle East, encompassing 100,000 feddans, which substantially increases the high need for skilled greenhouse workers.

What is now needed is to collaborate with Egypt in building green skills contributing to Egypt’s vision 2030 which aims to unlock the agricultural sector’s high growth potential – generating a large number of jobs, strengthening people’s resilience and achieving an increase volume of agriculture production by 30 % between 2020 and 2050.

Fresh commitments and new initiatives that were presented at the COP27 like the Presidential initiative Food and Agriculture for Sustainable Transformation (FAST) or the German G7 president’s CompensAction initiative should now focus on building a skilled workforce, able to develop and operate greenhouses and hydroponic farms in Egypt and the region allowing the countries in MENA to meet first of all their own targets in terms of food security but also the ever increasing demand for high-quality fresh produce for the European, GCC and African export market.

“The demand for hydroponic produce is already outstripping supply; building a new workforce is an integral and necessary part of a forward-looking agricultural and food security strategy” says Adel El Shentenawy, CEO of Hydro Farms in Egypt.

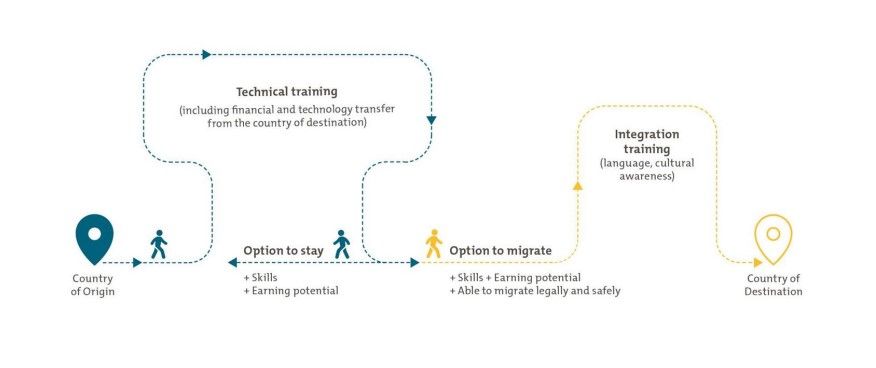

There is a universal simultaneous need for green-skilled workers. Importantly, the work to which they contribute –the green transition— is a global public good, no matter where it is conducted: everyone, everywhere, benefits from it. Soon-to-be-published research by the Center for Global Development, the ODI and IOM UK finds that this fact makes the green economy a labor market area peculiarly well-suited to Skills Mobility Partnerships (SMPs). In particular, given the existing lack of workers already trained, a migration model called the Global Skill Partnership (GSP) offers high potential. The GSP model, adopted into the 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM), sees a ‘two-track’ training and migration approach undertaken. The destination country funds training in the desired skills in the origin country. Some of those being trained are on the ‘away track’, and will migrate to the destination country; their training may incorporate modules needed for the destination country, such as language courses and particular certifications. Others are on the ‘home track’, and will remain in their own country and contribute to that labor market.

The Global Skill Partnership model

In the case of two-track SMPs focused on green skills, the funding country should have an unusually high interest in ‘home track’ trainees’ success. While green activities are rapidly becoming more profitable, their primary value lies in their emissions-reduction capabilities. Emissions reduction is a global public good, regardless of where it takes place. Green skills training could even be considered as a carbon offset category. Such green-skilled mobility partnerships will often focus on carbon emissions mitigation; in some cases, such as the Egypt-UAE hydroponic agriculture partnership, they can also clearly serve an important role in climate change adaptation.

Tanja Dedovic from the Regional Office of IOM in Cairo, Egypt agrees with the conclusions of the Center for Global Development in saying that: “New attention must be given to skills, if the green transition is to succeed at the pace and scale needed to meet the Paris Agreement. Given the global shortage of skilled workers in CSA, labor migration will be needed. To ensure that all countries can avoid skills bottlenecks, a migration model that combines migration with training is likely to be the most equitable and most efficient. In arranging green-skilled SMPs, partnerships should respond to anticipated skill gaps; be conscious of both developmental and emissions-reduction needs; and should seek country alignment (use existing migration corridors, leverage language skills) to reduce scaling time.”

The project team and its international partners are now fundraising for a pilot program to upskill CEA labor in Egypt in the hopes of filling the looming skills gap and establish related migration schemes.