For many in the agtech sector, the news that Monsanto Growth Ventures (MGV), the corporate venture arm of the agribusiness giant, has made about 12 investments since quietly making its first investment in early 2013, will come as no surprise.

While operating in quasi-stealth mode, the venture team, which consists of managing director John Hamer, venture principals Kiersten Stead and Ryan Rakestraw, and venture partner Darren Streiler, has, by many accounts, been a very active and dedicated member of the agtech VC community.

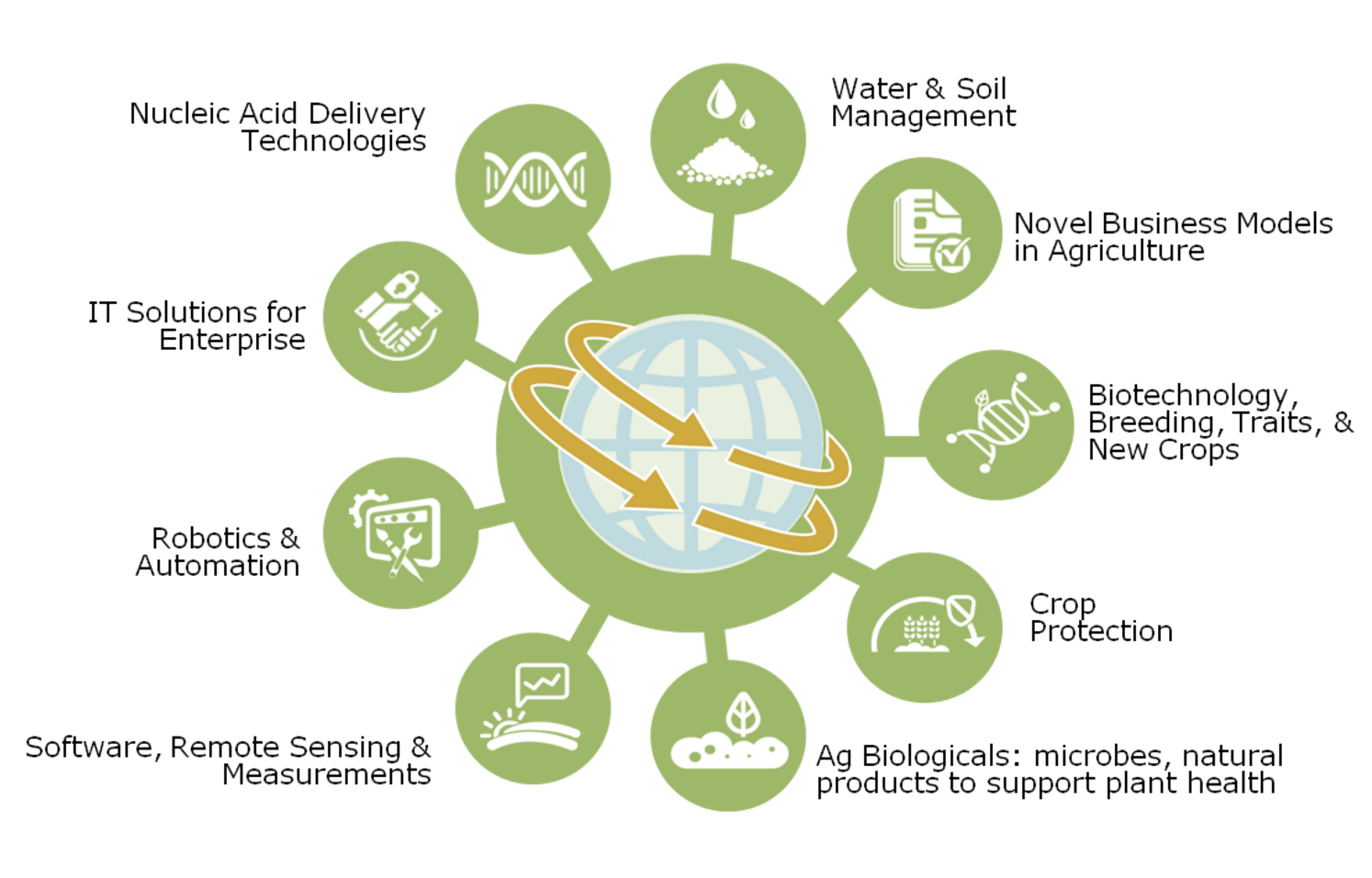

MGV is now about to close out its first portfolio of companies, making it the most active corporate venture arm in the food and ag sector, despite being a team of just four. And it has revealed the majority of its investments to AgFunderNews, some of which were not in the public domain previously. The investments range from precision agriculture technologies (40%) to life science companies (20%), ag biologicals (30%), and new crops and new business models (10%).

“In terms of activity, we are nowhere near Google Ventures or Intel Capital levels with hundreds of investments, but on a deals-per-investment professional basis, we have been quite active,” says Hamer.

As with many large corporates with VC arms, Monsanto knew early on that technology startups could be an important source of innovation and intelligence about potential competition coming down the pipe. The company was already an investor in some companies and life science funds before September 2012 when Hamer was hired to build the venturing arm. It was particularly involved in emerging genetic technology and had invested in some plant biotechnology, bioinformatic and genomic technology companies, generally as part of a broader collaboration. But these were mostly passive, minority equity investments and its life science fund commitments were even more indirect.

Realizing the potential for Monsanto to take things one step further and offer more involved support in the development of emerging agtech companies — with its deep agriculture expertise and access to agriculture markets — the global strategy group decided to formalize this effort with the creation of a full-time professional venture group, MGV.

And some active agtech-focused venture capital firms welcomed Monsanto into the sector.

“We see tremendous potential for transformational advances in agriculture, which is why we are collaborating with Monsanto Growth Ventures to boost startups…” said Scott Horner, managing director of Middleland Capital and one of MGV’s co-investors. “We have a front-row seat for innovation, and it’s encouraging to see both industry leaders and the investment community rally to support it.”

The success rate of corporate venture arms also played a role in the establishment of MGV, according to Stead, who pointed to a recent TechCrunch article, which states that corporate venture arms are responsible for 29 percent of venture funding and that their investments are three times more likely to see an exit than other startups.

MGV’s initial strategy centered around two major growth platforms within Monsanto — platforms that Monsanto was making considerable R&D investments in and later forming businesses in: precision agriculture and biologicals.

“We could see that Monsanto had a number of gaps in those areas so our first approach was to identify investment opportunities we believed could catalyze significant growth and be transformative for those platforms within Monsanto’s business,” says Hamer.

The Climate Corp story

One of the first companies Hamer and his team explored under this thesis was The Climate Corporation, which, as we all know, didn’t become a venture investment for MGV, but was instead acquired by Monsanto in October 2013 for $1 billion as the sector’s first unicorn.

This transaction influenced the development of the nascent corporate venturing arm, argues Hamer.

“Climate Corp opened my mind to us being not just an investment group providing $2 million to $3 million Series A rounds to startups, but that we could play a much more profound and expanded role in structuring partnerships, building out a network and identifying and accelerating potential M&A targets,” he tells AgFunderNews.

So Climate Corp, which could have been a late-stage investment and partnership, evolved into an acquisition when Hamer and his colleagues realized the potential for Monsanto to work with the startup’s data set and data scientists, and build software for growers themselves. “There were just so many synergies that, over time, there was a gradual realization on both sides that acquisition was the right route,” says Stead, who joined Hamer in February 2013.

Climate Corp isn’t the only acquisition MGV has helped to source; it’s also been intimately involved in the structuring and process behind the acquisition of YieldPop, Solum, and 640Labs.

The first venture investment deal the company made was in biological protection company AgBiome at Series A in April 2013. Monsanto was joined in the round by names such as Syngenta Ventures and ARCH Venture Partners.

Hamer was already acquainted with the founders of AgBiome after working with them at Paradigm Genetics, which was successfully acquired in 2005. Many of the founding members also exited Athenix: “this was probably the best team of ag entrepreneurs anyone could back,” says Hamer.

AgBiome is clearly a group that’s very strategic for Monsanto, and the company is ready to test AgBiome’s products and partner with the startup “in a significant way”, Hamer told AgFunderNews at the time of AgBiome’s Series B last year when the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation joined AgBiome’s investor base.

Then came AgSolver, a software and analytics systems company for sustainable land management, valuation, and business planning.

“They are interesting as they are doing things very differently to Climate Corp and are very much focused on the sustainability of agriculture and developing data systems and analytics on how to create a more sustainable farm ecosystem,” says Hamer. “Historically, they calculated how much available biomass there is across the US, and worked with several companies including Monsanto, to understand sustainable crop residue removal. They are also building interesting systems to understand farm profitability and land value.”

Data dive

Other investments in the digital, data segment of agtech, include Hydrobio, the prescriptive irrigation mobile platform, Blue River Technology, the robotic farming company, which recently closed a $17 million Series B round, and VitalFields, the Estonian farm management tool.

The remainder of the portfolio is in biologicals — PreCeres, PivotBio, Plant Response Biotech, and RaNA Therapeutics — and other field applications such as Arvegenix, the company transforming pennycress into a cover crop service, and Nimbus-Ceres, the fungicide producer.

There has been much discussion in recent months that the growing number of data collection and analytics companies offering a variety of similar services to farmers are causing confusion and concern that many will fail. Hamer believes this will result in consolidation among the smaller players.

“We believe in a world where growers will use data to make better decisions to increase efficiency and sustainability,” says Hamer. “We’re seeing the first wave of these predominantly ‘software-as-a service’ companies going through various types of growing pains from adoption rates and churn to tapping into farmer behavior to generating a real ROI for farmers. We definitely see these technologies moving to more of a platform service which will touch on more farm decisions, and as those become more integrated, the adoption curve will improve, and specific connected devices will be included. And the subsector will likely consolidate.”

So how does MGV source its deals?

The vast majority of deals come to the team through their existing connections with entrepreneurs or seed investors. Some of these entrepreneurs may have worked for Monsanto already or tested their technology with the company in some shape or form previously. “Eighty percent of our deals come through personal networks of individuals, investors, and entrepreneurs,” says Stead. “The remainder are sourced directly by us, or through Monsanto employees”.

MGV has led or co-led all but two of its investments and has invested alongside more than 50 different co-investors in a range of different structures from sole structured buyout transactions, to syndicated venture capital deals. MGV always has a minority stake and invests between $500k at the lower end, up to $15 million. The majority of deals so far have been in the $1 million to $3 million range.

“For syndicated venture capital deals, we try to form a nice syndicate of investors that have expertise the company needs depending on its subsector of agtech,” says Hamer. “We have been involved in tech companies and been doing ventures in the Bay Area for 12 years, so we have a pretty expanded network of VCs. We make it part of our effort to reach out to investment groups, get to know them and what they’re interested in, and think about how we can work with them on a transaction. We do spend a good portion of our time developing additional networks for different types of deals.”

MGV has three main criteria for investments: a strategic opportunity for Monsanto, an impressive founding team with a commitment to agriculture and “exceptional vision”, and an appealing potential VC return on investment.

Global goals

Geographically the company has made two investments outside of the US, and both are in Europe. Plant Response Biotech is based in Madrid Spain, and VitalFields is based in Tallinn, Estonia.

“Europe presents a compelling and different investment thesis from the US,” says Stead. “There is both more farmland in Europe/Ukraine, and there are more, typically smaller, farms to sell into. The practice of agriculture is also different. Crop protection is applied more frequently than in the US for example, and the regulatory/compliance burden is higher. This presents pain points for growers that can be eased by automation, data analytics, and software support.”

The challenges of investing in Europe — the securities laws that make venture investing more complex, and the difficulty presented in managing investments from afar — are partially offset by the diversification opportunity and the reduced cost of investing in European agtech companies, Stead adds.

The team is also keen to explore investment in other geographies, leveraging Monsanto’s global footprint. Hamer named Israel, Japan, Argentina, Brazil, Eastern Europe, Africa, and India as potential target markets.

“We are just beginning to roll out our global strategy, but it will include working with well-positioned investment syndicates with deep local networks and deal know-how,” he says.

Reputational risk?

While MGV’s reputation in the venture capital and agtech community is notably strong, it’s hard to ignore the broad-based negativity surrounding Monsanto, the corporation, due to its production and distribution of genetically modified seeds and glyphosate-based herbicide Roundup.

How does this impact the work of MGV? There have been some reports of entrepreneurs advised by VCs and other stakeholders to stay away from Monsanto due to the potential reputational risk of association with the agribusiness giant. While Hamer and Stead do not confirm these rumors, they argue that the main pushback they get is the fact they’re a corporate VC.

“The pushback we occasionally see is that we’re a corporate VC, although we do get the question about how our reputation will impact the company (although typically not from farmers or people in ag whose views are generally positive, so it is a strange dichotomy),” says Stead.

“But call any company we’ve invested in and our reputation will speak for itself,” adds Hamer. “We work really hard to build companies and management teams. We all have a background in institutional investment firms and all know the value of personal reputation as investors. Half our job is explaining Monsanto and dispelling myths and rumors to entrepreneurs and the community and vice versa. And mostly they want us in the room for our ag expertise and network.”

Expect a couple more deals from MGV before it officially closes out its first portfolio, and several more thereafter. This is a team that’s not slowing down for anyone.

Have news or tips? Email [email protected]