Now is the time to “separate the wheat from the chaff” when it comes to sustainable livestock production, says Justin Webb, co-founder of Australia-based livestock management software platform AgriWebb.

To help in that process by providing “a source of truth” for ranging operations and the agrifood corporates that use them, AgriWebb recently raised $7.2 million from existing backers Germin8 Ventures, Grosvenor Food & AgTech, and Telus Ventures.

The round also included participation from Swedish industrial company Munters Group.

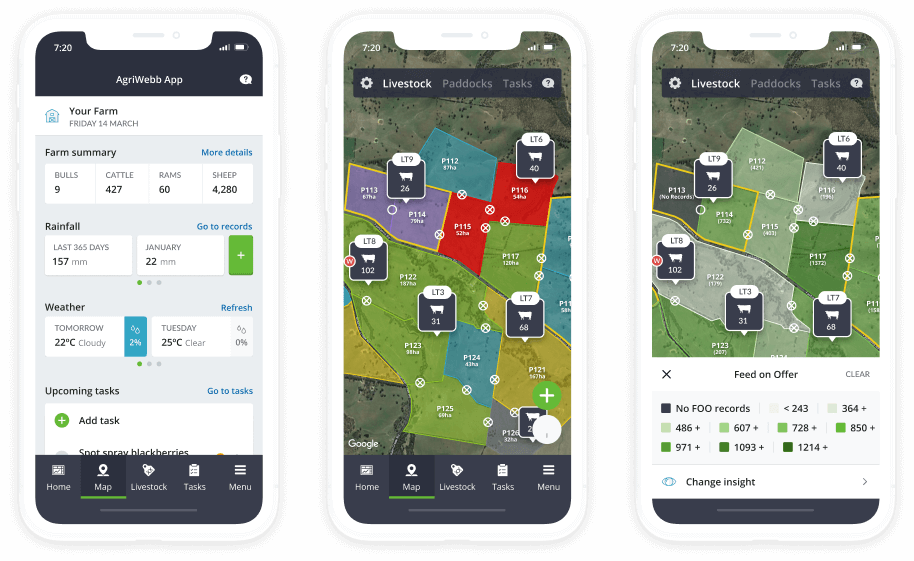

AgriWebb has developed a software-as-a-service model that collects data from the field and cowshed to provide livestock operations with farm mapping, grazing management, and inventory tracking, among other points.

Currently, the platform manages over 23 million head of livestock across more than 150 million acres, most notably in Australia, the UK, the United States and Brazil.

Connecting the supply chain

AgriWebb previously raised a $23.3 million Series B round led by Telus Ventures in January 2021.

Webb says that round was “really around raising capital to connect the supply chain” to its platform.

The company now has agreements with food corporates including Sainsbury’s and ABP in the UK as well as Cargill in Brazil, the latter being “a mutually exclusive arrangement,” says Webb. It also has a beef sustainability partnership with McDonald’s that focuses on the latter’s efforts around Scope 3.

“One of our big drivers was always to help farmers, in our case ranchers, record and digitize their assets, record their data, be more productive, and scale that SaaS business to the point that we could engage the supply chain up,” he adds.

AgriWebb will use the new funding to double-down on the commercial reality of sustainability — what Webb calls “connecting the consumer and the retailer back to the original producer for sustainability.”

The new funding and company focus for the immediate future will be directed towards the McDonald’s deal in which the fast-food giant pays ranchers for their baseline sustainability data and subsequent mitigation efforts. Ranchers will be rewarded for increasing biodiversity and lowering their carbon footprint.

A focus on insetting

Webb suggests right now is a critical time to separate operations that say they are sustainable from those that actually are, particularly when it comes to livestock and meat production.

“That’s become a massive driver for us. In particular, it’s been insetting, not offsetting.”

For example, in Australia, “you see a lot of noise around carbon project management and the excitement of carbon offsets and markets selling credits. While that’s fine in theory, it is in essence a license to pollute.”

He echoes similar statements from other climate-focused organizations and individuals that believe carbon offsets in many ways enable corporates to continue with business-as-usual operations and not actually change practices to foster more sustainable supply chains.

Carbon insetting, where companies invest in solutions within their own supply chains, is increasingly part of the climate dialogue, with major agrifood players such as Nestlé making public commitments to shift from offsets to insets.

“We are really prioritizing carbon insetting within companies that have meat in their supply chain,” says Webb. “How do we quantify what their Scope 3 emissions are? How can we have a source of truth that goes all the way back to the point of origin and then how can we mitigate that footprint?”

Headwinds and tailwinds for global meat production

“Within livestock production, there continues to be what we talk about as this Malthusian trap: not having enough food to feed the growing population.”

Oft-cited estimates by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations state that feeding 9.1 billion people in 2050 will require raising food production by 70%; production in the developing countries would need to almost double. Demand for protein in developing countries is also on the rise. Webb says much of this demand is for real meat.

While alternative meats — plant-based, cultivated, etc. — are welcome advances, they are not a replacement for meat, he claims.

“[They’re] not scalable yet to the point of totally replacing the existing production. So how do we make existing natural red meat production more sustainably efficient and effective? That to me is a major challenge.”

At the same time, there are now “unprecedented input costs and greater geopolitical tensions around output export, so you tend to see greater regulatory burden and reporting.”

Putting all that together results in “greater demand [for meat] that’s more expensive to produce, less certainty about your ability to sell off, and more precise reporting requirements.”

In essence, it becomes a productivity problem, he says.

“Technology should be able to help us here. But we’re also dealing with an industry that is inherently analog and very fragmented, much more so than almost any other area of agriculture. There is still the paradigm shift at large.”

He says AgriWebb currently has nearly 30% of sheep and cattle in Australia on its platform and more than 20% of the UK beef herd.

“Yet we are barely scraping the surface in terms of mass adoption. We’re talking 23 million head of the best part of 800 million head of commercial beef cattle globally. The challenges are faced by a very fragmented producer base that hasn’t yet adopted fully adopted and embraced technology as as a solution to that. That’s the headwind and the tailwind situation at the moment.”