Seaweed shows up frequently these days in agrifood products, from health supplements to additives that reduce methane in cattle. Another increasingly popular use case is putting seaweed extracts in biostimulants, something Namibia-headquartered Kelp Blue is currently doing with the help of its fast-growing giant kelp forests.

Founded in 2020 by oil industry veteran Daniel Hooft, the company cultivates these sea forests off the coasts of Namibia, Alaska and New Zealand, and has ambitions to expand all over the world.

Giant kelp grows faster and provides more frequent harvesting opportunities than many other types of seaweed, says Hooft, which makes it an economical choice for large-scale growing.

The company’s StimBlue+ product, into which the seaweed extract goes, can increase flower production and photosynthesis in plants, and also includes components that can help plants better withstand environmental stressors such as drought and extreme heat.

This year, Kelp Blue was named a finalist in the XPRIZE carbon removal program.

AgFunderNews caught up with Hooft as well as Kelp Blue head of agribusiness Valentine Pitiot to learn more about the journey from oil to seaweed and the promise of giant kelp in food and ag.

AgFunderNews (AFN): How did the company start?

Daniel Hooft (DH): I spent about 20 years in oil and gas all over the world: Africa, Russia, Australia, and I set up the company when we were living in Brisbane.

My wife had gone to a lecture by a scientist called Tim Flannery, who was proselytizing about what seaweeds can do for biodiversity boosts and for carbon. She came home part enthused and part astonished at this guy saying that seaweed at large scale would save the world.

I delved into it and started reading up. My background in doing oil and gas at large scale in difficult places was maybe perfect to try and take the seaweed industry from essentially a pretty manual one into something that’s more mechanized, automated, at scale, and to do it offshore.

That idea matured over six or seven months. I resigned, did some scouting trips to the various parts of the world where [seaweed farming] should work best — and that’s driven by nutrients and temperature of the water.

Namibia was the first place on that list because of the upwelling — the deep water that comes up close to the coast.

Then COVID broke out and forced us to focus, which in hindsight was very lucky. Instead of being a “world tour” first and wasting lots of money, we just dove straight into the country [Namibia] we thought should work.

We got licensed here in about a year and a bit, which is faster than you get in a developed country, and we started planting stuff in the water on 14 February 2022.

That first planting went well. Five weeks later we saw the first palm-sized plants, and five weeks after that, it was a 30-foot monster.

AFN: Why giant kelp?

DH: The main reason is that it’s perennial. In fact, more than perennial because the baby plants most prefer to grow on the holdfast [branching extensions the kelp uses to anchor itself to a rocky surface] of the old plants. So we seed the plants once and then until perpetuity can harvest those same plants.

At some point your ropes or structures will deteriorate, but that’s what drives the lifecycle of our forest, rather than a typical seaweed farm which [has to be] seeded once, and harvested once to redo the cycle every year.

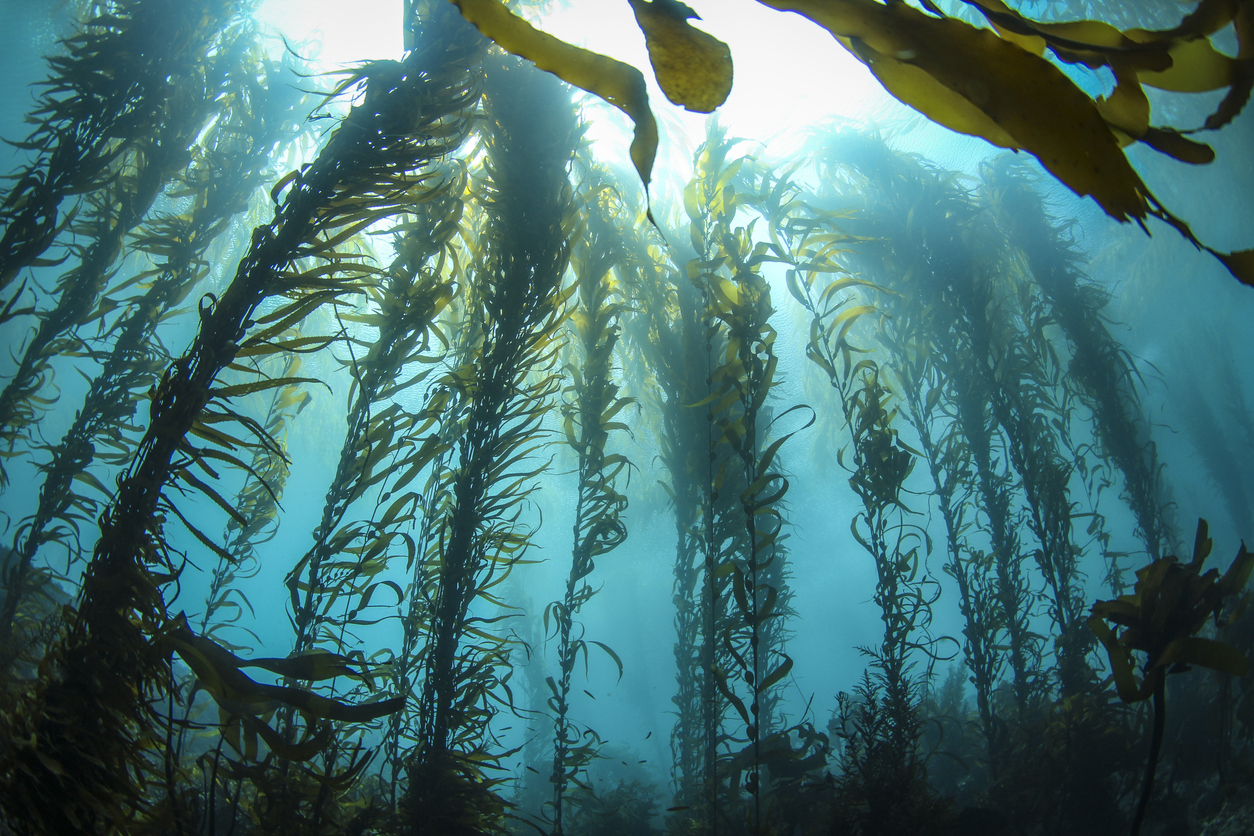

Another reason that is pretty fundamental to the economics is that this is one of the rare species that is buoyant. It rises up to the surface [of the water] and forms a canopy on the sea surface, and we trim that with a mowing machine. We take only the canopy and we leave the rest of the standing forest, and it will grow back by itself within three to four months.

Most seaweeds, if you cut them, will die back all the way and you have to reseed from scratch. And most seaweed grow downwards off growing ropes, which makes mechanical harvesting super difficult.

I just trundle over the surface with a harvesting mower. That also drops the harvesting costs which are typically 40% of a seaweed farmer’s costs.

Another reason is that giant kelp is one of the fastest-growing organisms on the planet; it’s by far the fastest-growing seaweed. As long as you seed it somewhere nutrients are rich, it will give you 150 tons of fresh seaweed yield per hectare, and no other seaweed is going to give you that.

Giant kelp is particularly rich in immune-boosting elements that make it able to grow fast in this really hostile environment. And that’s, of course, what we take into the biostimulant and what we pass onto land plants.

AFN: Tell us more about the biostimulant product

Valentine Pitiot (VP): We have a specific process to extract the molecules out of the seaweed to create the biostimulant.

This is interesting for farmers because it will help them to reduce the amount of fertilizers, and especially synthetic fertilizers, that they apply, and thus reduce the cost to have an overall positive return on investments on their farm.

So not only does it help them to build long-term profitability by having a great impact on the soil, [it also secures] short-term returns.

Currently, the price of fertilizers is skyrocketing, while soil quality is going down, and there is no solution at scale to answer this issue.

We started with Europe [for selling the biostimulant], but we have this vision to go to the different countries around the world to be able to have an impact on the farms and accelerate the shift to sustainability. And it doesn’t mean that we only target the organic farmers or small scale farmers. We also target the very large ones that want to shift [practices]. Every time they use one liter of biostimulant, there is seaweed planted. There is carbon sequestration, biodiversity boost, powering coastal and local communities.

So we not only work with farmers, but we also work with distributors and cooperatives. We also work with the big corporates, who have huge commitments when it comes to carbon emissions. And if you can reduce by 30% the amount of fertilizer on your field, the amount of the emissions will be drastically dropped.

DH: We are convinced that smarter, greener, multi-stakeholder thinking on how you run your business also makes your business more profitable. We’re not looking for some kind of green premium and for people to reward us because we’re doing something beautiful for the oceans.

What we sell works better for a farmer. Farm margins go up, their yields go up, their inputs go down. Their soil becomes healthier, which means that, in the long term, they’re putting less and less rubbish in there.

VP: We recently received field trial results on strawberries from accredited agencies by the government, so that we have a third party basically doing the doing the test.

When we applied the biostimulant, yield went up about 22%. This means per hectare for the farm, approximately $3,000 addition. For grapes, we have seen an increase of $5,000 to $10,000 per hectare.

AFN: What about a few challenges you’ve faced along the way?

DH: Certainly, there are regulatory challenges. Suddenly a bureaucrat or an obscure rule becomes something that holds you up. For a startup, time is money, and if there’s too much time, too much money disappears.

We had a number of issues, non intentional and not so many in Namibia, but hiccups in New Zealand and Alaska, for example, with registration of products.

Staffing an organization and then making sure you treat people right and you build the culture you want, that’s a challenge, particularly when you’re small. One or two of the wrong events or the wrong people can can sour the orange juice quite quickly, and so you’ve just got to stay on top of that.

We had a huge storm last year that wiped out all of our crop – thankfully not the structures. That sets you back.

Depending on where you are, kelp is susceptible to different things. In California it would be certain fish. In New Zealand we see a lot of skeleton shrimp, particularly when associated with salmon farms.

Here in Namibia, you’ve got something called a kelp louse. They are a bit like locusts. Some years you get swarms of them, and some years you get none. This year was particularly bad. From mid-June to mid-September, essentially everything was eaten. Our entire crop disappeared. By now the team is pretty resilient, and so we all acted very cool. But underneath you’ve got a bit of a bit of heartache while it goes on.

We were all very happy a few weeks ago when enormous amounts of plants were at the surface again, and it’s a nice lush forest again.

AFN: What’s next?

DH: In a nutshell, over the last two and a half years, what we’ve proven is that we can plant [seaweed] offshore, we can do that at scale, and it thrives in a very natural way, that we can do a nature-mimicking forest in the ocean that has a pretty incredible biodiversity boost. We see about 40x the number of species in the forest as before and a lot of bio-abundance growth: it’s a sort of hatchery for small fish and crayfish and lobsters.

We’ve proven we can do all this for the right amount of capital, for less money than we thought it would cost us. We’ve proven that the yield — the amount we can harvest — is where it needs to be. We trim the top of these forests regularly.

Once we were confident enough about all this, we put in a little factory. We have proven that factory does its job and that it operates at the cost we need it to.

Most importantly, the biostimulant, the plant booster that we produce from the seaweed extract, is a pretty amazing liquid, and has great results on a number of crops.

Our whole technical feasibility is proven up. We’ve got a license of about 15,000 acres.

The only matter that remains is feeding the investor pipeline of revenue into offtake agreements. So that’s our main focus at the moment, for Valentine and his team to take this product out to market and do the long, hard slog of convincing farmers to buy it.