Himanshu Gupta is the co-founder and CEO of ClimateAi, a supply chain resilience company that was recognized in 2022 by TIME Magazine as one of the greatest innovations of the year. He has worked in the climate space for over 15 years, including working with former Vice President Al Gore, as well as serving as the lead modeler for the Emission Pathways project for India. He holds a joint MBA/MS in environment and resources from Stanford.

These past two months in California have been the rainiest, snowiest, and generally wettest in recent memory. The picture of a dry, brown Golden State might seem like it could soon disappear, but in reality, this precipitation is a drop in the bucket of California’s years-long drought. In fact, 2022 marks the state’s fourth consecutive year of large-scale dryness and drought; reports show its major reservoirs are still depleted.

As water managers and companies plan their operations for the year ahead, we cannot let this recent rainfall lull us into a false sense of complacency around water management and risk our long-term water supply.

To assume that California’s water resources will be renewed this winter is willful ignorance in the face of climate change

As a California-based climate-tech entrepreneur who works with global companies on water risk mitigation, I have seen firsthand how both public and private sector decision-makers take our limited water resources for granted.

For context, California’s water supply comes from both groundwater (underground saturated zones, called aquifers) and surface water (streams, rivers, lakes, and reservoirs). A complex statewide system with connected dams, reservoirs, pumping stations, and canals makes water available for use.

However, climate change brings shifts in precipitation patterns, reduced snowpack, higher temperatures, and more frequent droughts, all contributing to the decreased availability of renewable surface water. This increases demand on often nonrenewable groundwater sources.

California has experienced drier, hotter conditions on average for the past two-plus decades, which is depleting surface water resources and straining the water system, Municipal, industrial, and agricultural actors have compensated by extracting more groundwater, with disastrous impacts.

Consider Pajaro Valley, one of the state’s most agriculturally productive regions. Its Mediterranean climate has meant that for decades, farmers have drained saturated fields during wet winters, then irrigated those same fields with groundwater during dry summers, resulting in overdrafting.

About 95% of the water used for agriculture in Pajaro Valley is groundwater. Long-term problems have compounded, including higher energy use (to extract ever deeper groundwater), sinking lands (due to soil compaction), lower water quality, reduced streamflow, and oceanic saltwater intrusion (saline water kills crops).

Situations like these are common across California. Our recent rainfall cannot trick us into thinking and acting like there are no massive long-term water issues to solve.

Have we learned anything from the last historic drought — only eight years ago?

The southwestern portion of North America is experiencing a climate change-exacerbated 22-year-long megadrought, its worst in at least 1,200 years. California specifically saw its warmest, driest period on record between 2012–2016. It created water shortages for agriculture, hydropower, rural groundwater supplies, recreation, aquatic ecosystems, forests, and cities, costing billions of dollars in economic losses and less quantifiable environmental impacts. Then, after one wet winter in 2016, the state lifted its mandate of a 25% reduction in urban water use, letting localities set their own conservation standards (even as moderate to severe drought still gripped three-quarters of California).

Consequently, companies continued overdrafting nonrenewable groundwater resources. In addition, many riparian ecosystems experienced continued degradation as “environmental minimum flows” could not be met.

Now, the state has plunged into drought again. Why do we try to go back to “normal” during one wet year when we know drought is always around the corner?

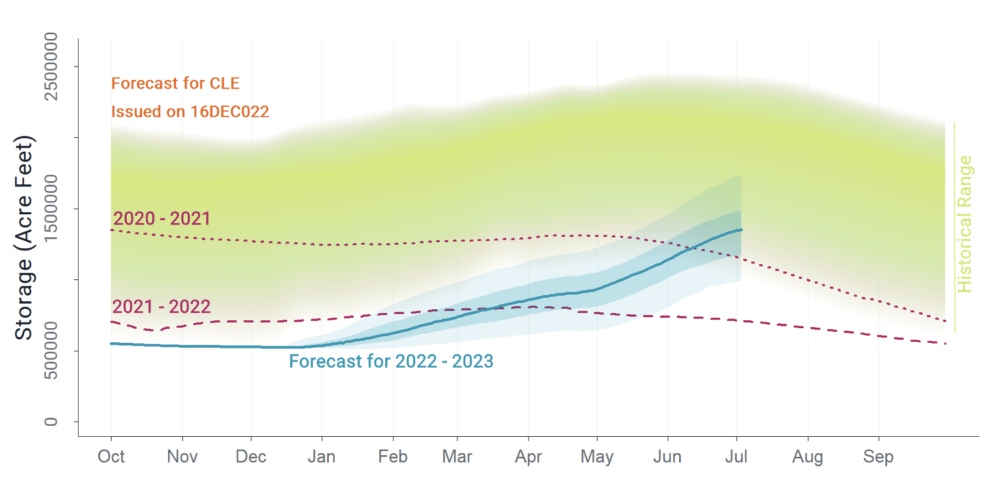

We cannot afford to make the same mistake this winter. Our forecasts show that while California is expecting higher-than-average precipitation, it will not be enough to significantly curve the arc of our ongoing drought. For the majority of state reservoirs, this year’s elevated precipitation will help total storage exceed that of the previous two years, but remain well below historical averages.

For example, one of California’s largest reservoirs, Trinity Lake, is currently only 21% full. We found that historically, Trinity Lake’s water levels generally can recover from such low levels back to average levels after minimum two reasonably wet years. (Still, every reservoir/location responds differently.)

The majority of the past three decades have seen dry or drought conditions. We must recognize that dryness is the “new normal,” and wet years are the exception. The amount of water available now is at best likely to stay the same or at worst significantly decrease in the coming decades. Our water management approaches must shift accordingly.

What decision-makers can do

It’s not all doom-and-gloom. Companies and water managers have the agency to implement solutions across their operations to improve management practices and systems.

One action that private industry can take is to artificially recharge aquifers (also known as water banking). Redirecting excess wintertime water into a “recharge zone” — a pre-existing or engineered depression that collects surface water so it naturally infiltrates the underlying aquifer — can help mitigate the effects of long-term groundwater overdrafting.

This combats one facet of climate change that California faces: The mountainous Sierra Nevada watershed that historically provided plenty of state water is suffering. In the past, snowpack slowly melted in springtime and filtered into reservoirs. Warming temperatures have meant less snow and snowpack. Instead, water from winter rains (called “overspill”) now quickly splashes down, not captured as usable water in reservoirs, even threatening to flood.

Remember Pajaro Valley? In 2010, top berry company Driscoll’s identified an existing basin on a privately owned site, the Bokariza Infiltration Basin, where winter-time stormwater could be redirected for effective aquifer recharge.

Additionally, when companies understand their water supply limitations, they can prepare to minimize losses and identify new opportunities. For example, while the 2012-2016 drought hit the state’s agricultural industry hard, farmers were largely able to shift production to more valuable crops (even with less water available for irrigation) to avert greater economic losses.

Every time it rains, you’ll hear Californians say, “We needed this.” While that’s the truth, we must get neither overexcited nor complacent. Just last week, the country’s largest water provider declared a new drought emergency in Southern California. We’re not out of the water yet.