On paper, cultivated meat might seem like a no-brainer. Unlike plant-based options, which still don’t quite hit the spot for many consumers, it promises the allure of ‘real’ meat without the ethical and environmental baggage that comes with plundering our oceans and raising billions of sentient land animals for food.

In practice, however, there’s no playbook for biomanufacturing meat at scale. The funding environment has changed dramatically as investors have soured on alt proteins, and we don’t know whether consumers will pay a premium once the novelty wears off.

The media narrative around cultivated meat, which was universally positive a few years ago, has also changed dramatically over the past year: Articles about innovations in the space now compete with headlines about cancerous cells, greenwashing, vaporware, and business failures, against a backdrop of grim quarterly results from plant-based meat brand Beyond Meat.

So, can cultivated meat make the transition from a loss-making novelty served at a handful of high-end restaurants to a commercially viable alternative to animal agriculture?

“The money has dried up, but not fully. There are still companies that have been able to raise, but these are really the leaders in the space or those with unique technologies.” Ryan Bethencourt, Sustainable Food Ventures

First, the bloodbath…

Healthy skepticism is understandable given the momentous challenges facing first movers in any new field, observes Ryan Bethencourt at early-stage investor Sustainable Food Ventures, which has invested in multiple startups in the field including cell-cultured seafood company Umami Bioworks and cell-cultured fat company Hoxton Farms.

However, it seems somewhat premature to write off an industry that didn’t even exist a decade ago because it can’t immediately compete with a heavily subsidized industry (industrialized animal agriculture) and associated ecosystem that has been scaling up and driving efficiencies for decades, he remarks.

“Probably 70-90% of companies in this space are going to fail over the next year, but those that survive will build real businesses and will scale their technologies,” Bethencourt tells AgFunderNews. “This is just a normal part of the cycle [for new tech].

“There’s a lot of anxiety right now and unfortunately, everyone looks at Beyond Meat and says, this ‘future of food’ space is dead. It’s not. The money has dried up, but not fully. There are still companies that have been able to raise, but these are really the leaders in the space or those with unique technologies. And honestly, this [challenging funding environment] applies not just across the future of food space, but across almost every vertical except for maybe AI.”

Laura Turner, principal at Agronomics, which has invested in several cultivated meat players including Meatable and BlueNalu, adds: “There are a handful of pre-seed and seed stage companies that will never make it to series A, and those that have the funding better make sure they stretch it out another 24 months. I’m optimistic the funding environment will improve next year, but it could still be another 18 months before it picks back up again. And to entice generalist capital back into the space we, we need success stories.”

“We are going through a market correction. Cellular agriculture was in a bubble and there was mispricing… leveraging biology to produce commodity items takes time. Now, any company trying to raise a series B in this environment… instead of raising $300 million you’re lucky to get a $30 million round done. The days of using extensive equity to finance capex are over.” Laura Turner, Agronomics

Cultivated meat, a timeline:

- 1931: Winston Churchill publishes essay, Fifty Years Hence: “We shall escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing, by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium.”

- 1997: Willem van Eelen files patent for the Industrial Production of Meat Using Cell Culture Methods.

- 2001: NASA funds experiment on producing fresh meat for space flight by cutting strips of flesh from goldfish and submerging them in a nutrient bath extracted from the blood of unborn cows.

- 2005-2009: Dutch government funds the Dutch In Vitro Meat project.

- 2010: Isha Datar publishes ‘Possibilities for an in vitro meat production system.

- 2011: Andras Forgacs founds cell-cultured meat and leather company Modern Meadow.

- 2013: Dr. Mark Post unveils cell-cultured burger at press conference in London.

- 2015: Yuki Hanyu launches the Shojinmeat Project in Japan.

- 2016: Memphis Meats (now UPSIDE Foods) unveils cell-cultured meatball.

- 2020: GOOD Meat (Eat Just) launches cultivated chicken in Singapore becoming the first company to commercialize cell-cultured meat; Aleph Farms unveils thin-cut cultivated steak prototype.

- 2022: Believer Meats breaks ground on the industry’s first commercial-scale plant in North Carolina, USA.

- 2023: New Age Eats shut down; GOOD Meat and UPSIDE Foods secure FDA/USDA approvals, launch cultivated chicken in the US.

“We can achieve price parity today if we operate at scale, without relying on future innovations. And we can do that with the 10,000-liter bioreactors we’re planning in our pilot plant, whereas others require really large bioreactors that haven’t been validated.” Dr. Ali Khademhosseini, Omeat

Is cultivated meat commercially viable?

So where do things stand right now from a scientific and technical perspective?

While it’s still early days, significant technical progress has recently been made on multiple fronts that suggest the future may be brighter than it looked even a couple of years ago, insists Dr. Elliot Swartz, principal scientist, cultivated meat, at nonprofit The Good Food Institute (GFI).

“I always say to people, if you look at the published peer-reviewed literature today [owing to the lead times], you’re getting a snapshot of where things were two or three years ago. Whereas through grant applications and pre-publication data and conversations we’re having with startups and academics, we’re seeing what’s happening now, and there is a lot of progress, although the big challenges remain cost and scale.”

Cell culture media costs

On cell culture media, for example, a key cost driver for cultivated meat, he says, “We’ve seen a lot of creativity replacing some of the higher cost ingredients such as albumin and transferrin with plant protein isolates and other food grade ingredients as well as growth factors [which can now be made in everything from barley to fruit flies as well as E.Coli]. I’ve spoken with several different companies that have been able to achieve costs considerably below $1 per liter.

“In parallel with that, you can add media supplements that enable you to use significantly fewer growth factors, or engineer cells to require fewer growth factors.”

He adds: “There are also companies using big data, AI, and machine learning that help you improve your feed conversion rate, which can work in tandem with models that allow you to understand the limiting factors in cell growth from a metabolic perspective.

“So, it could just be that the reason your cell isn’t growing is because it just needs more of a single amino acid. These sorts of computational approaches can help you determine that [and optimize your media formulation accordingly].”

At UK-based cultivated fat startup Hoxton Farms, for example, cofounders Dr. Max Jamilly (a synthetic biologist) and Ed Steele (a mathematician) are deploying machine learning to optimize their process.

According to Jamilly: “We run searches to find the best possible way of feeding and growing the cells to achieve the most scalable and cost-effective process and we can do it way faster than if we were running those same experiments in the lab.”

He adds: “We’re trying to increase the proportion of the cells that differentiate, but we’re also looking at how much fat they accumulate. How big and delicious are the droplets inside the cells? The size of the fat droplets has a really big effect on the taste and the way the fat cooks.”

Optimized cell lines

Companies such as Triplebar have in turn developed ‘accelerated evolution’ technology that can help cultivated meat startups develop cell lines with specific characteristics such as the ability to grow in single-cell suspension at higher densities without having to adhere to microcarriers (edible beads that take up room in the tank and must be incorporated into the end product or detached at high cost later), says Swartz at the GFI.

“The technology accelerates the evolutionary process for [microbial or animal] cells so you can obtain phenotypes of cells [with desirable qualities] in a faster, more direct, more reproducible manner. These kinds of companies are going to play a key role in helping create optimized cell lines more rapidly.”

Dutch cultivated meat startup Meatable and UK-based Uncommon (formerly Higher Steaks), meanwhile, claim they can dramatically improve the unit economics of cultivated meat by increasing the speed and efficiency of the cell differentiation process.

Israeli startup ProFuse Technology in Israel has developed a cocktail of small molecules that can dramatically accelerate muscle cell differentiation, says Swartz. “Their data is exceptional.”

“Costs have been somewhat debated, but let’s say it’s 50% consumables, 50% ingredients, 25% labor, and 25% building and bioreactors. If you increase cell density, you reduce the component of the bioreactors because you use them more efficiently, but it’s only 25% of the cost. If you reduce the amount of medium that you need for an amount of consumables to make that kilo of meat, that’s where you have the big gain.” Dr. Mark Post, Mosa Meat

Dave Humbird: ‘The emperor has no clothes’

Dr. Dave Humbird, chemical engineer, engineering consultant and author of a high-profile techno-economic analysis on cultivated meat a couple of years ago, is not convinced, however.

The price of cell culture media components will come down with economies of scale, he says, but what’s going to drive that scale in this chicken-and-egg situation the industry currently finds itself in?

“The price of individual amino acids and growth factors is going to be a strict function of the market volume,” he tells AgFunderNews. “None of this stuff makes any commercial sense until everyone’s eating it. The emperor has no clothes.”

Hybrids vs. whole cuts

So how does the industry resolve this classic Catch-22 conundrum?

By walking before it tries to run, says Josh March, cofounder at San Leandro-based startup SCiFi Foods.

Right now, it’s not commercially viable or technically feasible to crank out 100% cell-cultured filet mignon steaks at a massive scale, he says. But if you’re proliferating cultivated cells to feature as an ingredient in plant-based burgers and sausages at inclusion rates of 10-30%, the unit economics start to look far more favorable, he argues.

“You can make a blended product commercially viable at an affordable price at a relative scale using existing technology without needing crazy-scale bioreactors. I think you need genetic engineering and synthetic biology to get to that point, but still, it’s viable. We start to see a big flavor impact, even at a 5-10% inclusion rate, and the more you add, the cells mask a lot of the plant-based off notes and bring in a lot of beefy notes.”

With current technologies, whole-cut products such as steaks present far greater technical challenges than unstructured products such as nuggets, concurs Swartz at the GFI, noting that UPSIDE Foods is still making its whole-cut chicken filets in two-liter flasks, which COO Amy Chen concedes is not currently scalable.

However, its process for making unstructured products—growing cell biomass in far larger 2,000-liter tanks before combining it with plant proteins to make hybrid products—holds more promise (although UPSIDE is still awaiting regulatory approval on this process).

“You can make a blended product commercially viable at an affordable price at relative scale using existing technology without needing crazy-scale bioreactors.” Joshua March, SciFi Foods

Synthesis Capital: ‘Right now, a 100% cultivated product we don’t think is viable, but nor is it required’

“I think the predominant approach for the time being is going to be a hybrid approach, where you’re taking primarily undifferentiated cell biomass and blending that with plant-based ingredients in varying percentages for cost and simplicity,” says Swartz at the GFI. “I think it would be wise if the industry let structured product development [steaks, chops] happen more in academia at this point.”

Right now, adds Synthesis Capital managing partner Costa Yiannoulis, “a 100% cultivated product we don’t think is viable, but nor is it required. I think it’s a hybrid world. Even with very low inclusion rates [of cultivated cells, especially fats], you can really start telling the difference.”

According to Dr. Mark Post, cofounder and CSO at Dutch cultivated meat pioneer Mosa Meat, “For fat, we find that a very small percentage, actually much smaller than you typically find in a hamburger, is enough to turn a run-of-the-mill plant-based hamburger” into something far more ‘meaty.’

“For muscle, it’s a little bit different because that adds less to the taste and less to the cooking behavior and more to the nutrition and texture.”

Fellow Dutch startup Meatable is also adopting a hybrid approach, says cofounder and CEO Krijn de Nood: “If you make a hybrid product with just 10% of our product, there’s a big step up in quality, but we’re looking at about 50:50 [plant-based vs cell-based meat].”

Techno-economic analysis

San Diego-based BlueNalu, by contrast, intends to launch with whole muscle Bluefin tuna toro, a high-value product that commands a premium price, says CEO Lou Cooperhouse, who currently operates out of a pilot facility in San Diego. He hopes to break ground on a large-scale plant in 2026, although he has not yet secured sufficient funding to make this happen.

While the unit economics of making chicken nuggets in a bioreactor are likely to be challenging for some time, said Cooperhouse, making Bluefin tuna— “the Wagyu beef of the sea”—from cells makes a lot more economic sense.

According to a techno-economic analysis conducted last year, BlueNalu can achieve margins “north of 70%” with a 140,000 sq ft facility housing eight 100,000-L bioreactors producing 6 million pounds of bluefin tuna toro a year, claims Cooperhouse.

“We have identified what that cost will be [to build and operate a large-scale plant], but I think given the value of Bluefin tuna, the rate of return will be quite rapid. And that’s based on selling at price parity [with conventional tuna], even though consumers have said they’re willing to pay a premium for this type of product.”

“The price of individual amino acids and growth factors is going to be a strict function of the market volume. None of this stuff makes any commercial sense until everyone’s eating it. The emperor has no clothes.” Dr. Dave Humbird

Costings for commercial-scale facilities

But how much does it cost to build a commercial-scale cultivated meat facility, and will companies need to build vast, and vastly expensive, bioreactors for the economics to add up?

UPSIDE Foods— which has raised a jaw-dropping $608 million to date—is pumping $140 million into a commercial-scale facility in Illinois that will become operational in 2025 with the potential to produce 30 million pounds of meat.

It will have a range of bioreactors going up to 100,000-liters with “attractive unit economics,” according to UPSIDE Foods COO Amy Chen, who tells us: “We have enough [capital] to get it going and then to build a meaningful amount towards that full 30 million capacity, so at least the first few phases.”

According to court filings from bioreactor specialist ABEC, which is suing GOOD Meat for not paying its bills, the sums involved for a site with larger bioreactors are staggering (or to quote one investor in the space, “completely looney”). “GOOD Meat was woefully undercapitalized from the beginning, especially considering that the whole endeavor [a facility featuring 10x 250,000-liter bioreactors] was likely to cost more than $1 billion, with commitments to ABEC for ABEC’s portion of the project alone likely exceeding $550,000,000.”

GOOD Meat founder and CEO Josh Tetrick won’t comment on the litigation, but told WIRED he’s now focused on finding ways to build cultivated-meat facilities that cost “ideally below $200 million” but says it goes without saying that the first commercial-scale cultivated meat facilities “are necessarily going to be more expensive.”

Whether Eat Just—recently described by one investor as a “house of cards built on one individual’s ability to separate people from their money”—will be able to secure these sums in the current environment is unclear, however, with one industry source telling us, “The cultivated meat business has a different risk profile to [plant-based egg business] Just Egg and should have been spun out as a separate business.

“I think it’s going to be very hard for them to keep going. Hats off to them for getting the approvals in Singapore and the US, but I don’t see a path forward.”

Bioreactors: Size matters, but we don’t know the sweet spot yet

While size matters, you don’t have to spend millions on 250,000-L bioreactors (uncharted territory for animal cell culture) to achieve commercial viability, claims Dr. Gabor Forgacs, co-founder at Fork & Good, which recently opened a pilot facility in New Jersey.

“If you’re making batches in a 250,000-liter bioreactor and there’s a contamination, that’s an astronomical amount of money you stand to lose,” adds Forgacs, a biophysicist who first produced cultivated meat over a decade ago at startup Modern Meadow.

Fork & Good will probably “not need to go much beyond 1,000-liter bioreactors,” he predicts. “Using our continuous harvesting approach, in a month, you can generate 100 times more biomass by using ten 1,000-liter bioreactors, than what you’d get using a batch process with one 10,000-liter bioreactor.”

Post at Mosa Meat adds: “We don’t know what that sweet spot is yet for bioreactors. It’s quite clear that there are economies of scale. However, if large bioreactors get contaminated, you run a big risk. We’re starting with 1,000-liter reactors in our scale-up plant in Maastricht, but this is not our end game.”

De Nood at Meatable adds: “We are scaling up to the 500-liter scale. But what we have proved due to the efficiency of our process is that we don’t need big bioreactors. [At full commercial scale] we’ll need about 50 cubic meters [50,000-L], which is still very significant, but we don’t need to go higher than that.”

Los Angeles-based startup Omeat—which recently emerged from stealth with what it claims is a “simple and elegant solution” to scaling cultivated meat production involving the humane extraction of growth factors and other components from “healthy, living cows”—is also confident that smaller, cheaper, bioreactors are viable.

“The exciting thing is that we can achieve price parity today if we operate at scale, without relying on future innovations,” claims founder and CEO Dr. Ali Khademhosseini. “And we can do that with the 10,000-liter bioreactors we’re planning in our pilot plant, whereas others require really large bioreactors that haven’t been validated.”

Investing in cultivated meat: ‘There are companies that I’m pretty confident can raise enough capital to get into the market’

As for investment capital, the last 18 months have been hugely challenging for startups in alt protein, says Ryan Bethencourt at Sustainable Food Ventures. But several VCs are “raising record amounts for new funds and they’re going to have to deploy that capital somewhere,” he argues.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if by Q1 and Q2 next year we actually start to see investment activity picking up. All it takes is one of these VCs to see something that works to be able to pull the trigger and provide significant funding. There are companies that I’m pretty confident can raise enough capital to get into the market.”

Meanwhile, the big meat companies and other strategics are still watching this space, he adds. “In biotech, the smaller companies develop the technology and then license or sell it to big pharma companies, and that’s what’s going to happen in food.”

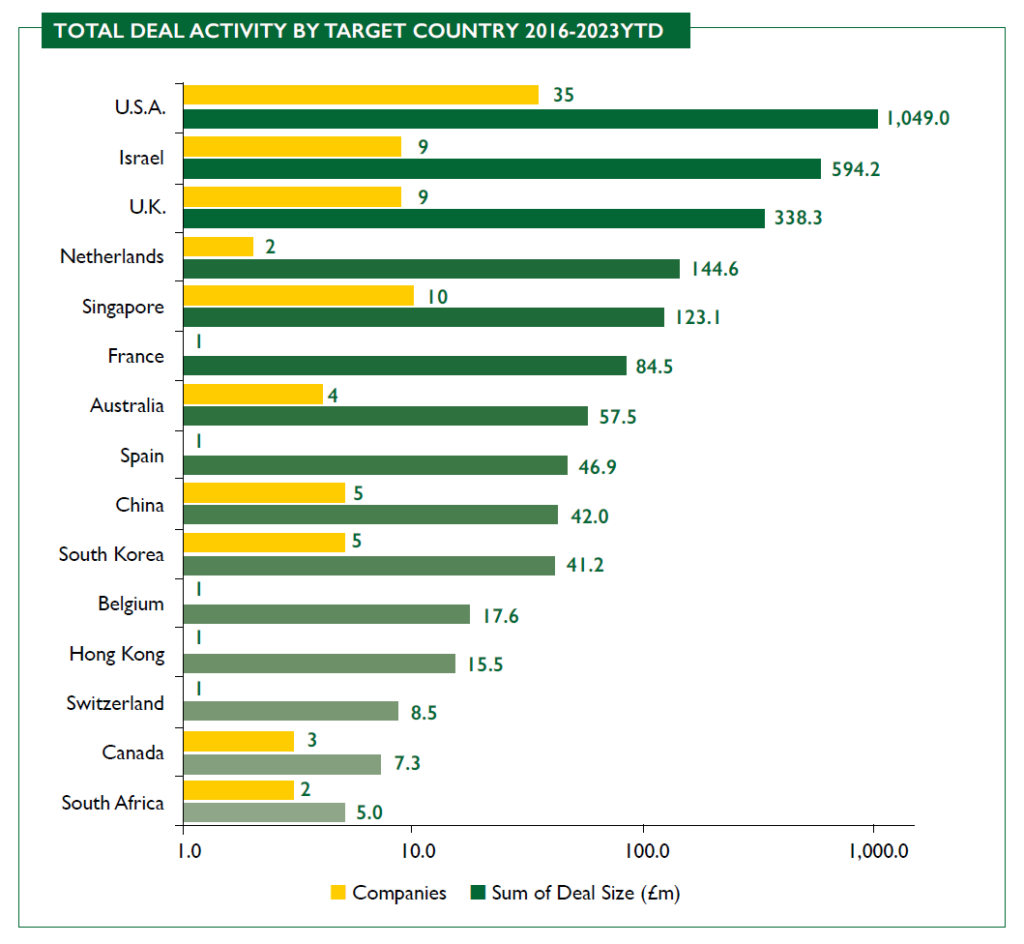

Going forward, all eyes are on sovereign wealth funds with deep pockets and a long-term strategy to tackle food security, says principal Laura Turner, “Agronomics has spent quite a long time in the Middle East, where food security is top of mind if you’re importing the majority of your food, so you see the NEOM Investment Fund [backed by the Saudi sovereign wealth fund] recently putting $20 million into BlueNalu, and that is exactly the source of capital we expect to see coming into the space going forward…that’s kind of how we see it going as western VCs have got a little scared of the space.

“The Abu Dhabi Growth Fund also put money into UPSIDE Foods while [DisruptAD, the venture capital arm of the Abu Dhabi holding company] ADQ invested in Aleph Farms.”

Synthesis Capital: ‘We wouldn’t invest in a company that’s purely servicing the cultivated meat industry’

Rosie Wardle, cofounder and partner at foodtech investor Synthesis Capital, says her firm has invested in companies that provide enabling technologies that can support players in cultivated meat, but says its too risky to put money into a company solely dedicated to that space right now.

“We wouldn’t invest in a company that’s purely servicing the cultivated meat industry as we don’t really see exit potential for our fund in investing in a media formulation company or a company solely doing cell lines for cultivated meat, for example.

“What we like about [recent investment] Triplebar [which develops more efficient biomanufacturing platforms utilizing microbial or animal cells] is that it’s de-risked because it can service multiple industries and the potential customer base is very broad, although we still believe in the cultivated meat industry in the long term.”

Nick Cooney at Lever VC, which has released internal benchmarks for assessing early-stage cultivated meat companies to help investors place more informed bets, says he’s also a believer in the long-term potential of the category, but adds:

“My candid view is that if you made a Venn diagram of companies that have received meaningful funding and companies that have what it takes to succeed, I think there’s only modest overlap between those two.”

In some cases, “after we start looking more closely, we find out that even though their pitch deck cites a number, it is in fact a projection that they expect to get to in 5-10 years,” adds Lever VC scientific associate Jasmin Kern.

Looking ahead, says Cooney, “A number of startups will go under, and to be impolite they probably deserve to in that they don’t have enough unique value that it makes sense for investors to keep putting money into them.”

“Does this industry need government funding to get off the ground? If you had asked me this question a year and a half ago, I would have said no. Now the situation has somewhat changed and when I look at the discussions about energy transition and other major changes in industry, where they’re really looking at governments for support, I’m starting to think that we probably would require something like that as well.” Dr. Mark Post, Mosa Meat

‘Astonishing’ startups?

According to Cooney, despite the drop-off in funding to alt protein players in general over the past 18 months, the pace of new entrants hasn’t really slowed down noticeably although it’s going to be tough to raise money in cultivated meat now “unless you’ve got a really revolutionary approach,” he says.

That said, he adds, “While we’re still seeing some very generic pitches, we’re also seeing new entrants with things that astonish us.”

Kern adds: “Quite a few of the cultivated meat companies we’ve been meeting with over the past three or four months have had novel technologies that we think could disrupt the space.”

Stray Dog Capital managing partner Lisa Feria, who has invested in several high-profile cultivated meat startups including UPSIDE Foods, Mosa Meat, BlueNalu, and Aleph Farms, says she expects to see several players go out of business in the short term, but remains “bullish” about the category’s long-term prospects.

“We recently invested in a company called Clever Carnivore, and they have been able, in a very short period of time, to climb up the cost curve so quickly that we’ve never seen this with almost any other company that we’ve talked to,” she claims.

The fact that meat giant JBS is investing to build the largest cultivated facility in the world also sends an important signal about where it sees the market going, says Post at Mosa Meat.

“We see a lot of involvement of large meat companies like Cargill and Tyson and JBS. When small startups with interesting technology cannot quite make it, we will see that at some point they are acquired by large companies. I don’t think the large meat companies can afford to let this dwindle and die, but for sure, there is an interesting and stressful period ahead.”

‘Skeptics have an important role to play, but the world isn’t changed by people telling you how you can’t do something’

Andrew Ive, founder at Big Idea Ventures, which has invested in multiple players in the cultivated meat ecosystem, concedes it’s a tough funding environment for startups, but says he’s encouraged by the level of interest from governments all over the world that see alt protein as key to food security in the long term.

“We’re having discussions from the Middle East to Asia about helping countries build ecosystems around alternative proteins in order to gain more control over their food systems. In the US, the Biden Administration is allocating more than $1 billion to biotech and biomanufacturing; the Netherlands allocated €60 million to cellular agriculture last year and is about to allocate a lot more; and this week Germany announced €38 million for alternative proteins, so I do see more non-dilutive funding coming online to support companies in cultivated meat.”

As for the naysayers, he says, “skeptics have an important role to play, but the world isn’t changed by people telling you how you can’t do something. Change is driven by people who solve problems. Animal factory farming kicked off in the 1920s, so we’ve had more than 100 years to become efficient at killing and harvesting billions of animals. I think people should give cultivated meat space a few more years before writing it off!”

Is there room for new players?

So what does this mean for brand new players entering the market? Are they wasting their time, or are things actually easier than they were five years ago when startups were having to invent an industry from scratch?

Doug Grant, CEO at Atlantic Fish Co, a new player based in North Carolina focusing on white fish, tells us: “When UPSIDE and co started, there was no regulatory framework. There was no ecosystem to support them. Today, there are a lot of companies building picks and shovels to support this industry, so startups don’t have to go full stack.

“Yes, the funding situation is pretty terrible right now, and some investors have made their bets and want to see some of these products get to market before placing any more, but entering the space now, we can do a lot more with a lot less.”

The journey of technology through time

According to Tetrick at GOOD Meat (Eat Just): “If someone says there are uncertainties around scaling up cultivated meat to tens of millions of pounds and getting below the cost of conventional chicken, beef or pork and lamb, I agree.”

But that doesn’t mean that cultivated meat is a foodtech fantasy, he insists: “The first cell phone that came out was this big, bulky thing. And if someone had said eventually it’ll be a phone in your pocket with 10,000 songs and access to the internet, you’d have said that can’t be because we don’t have the processing speed or the internet connectivity to do that.

“The journey of technology through time is to continue to build on the foundation you have and identify more efficient, faster, more effective ways to do things. Cultivated meat is no different.”

Post at Mosa Meats adds: “Is this a big endeavor with some level of uncertainty? Absolutely. Is it so unrealistic that you shouldn’t even try? Absolutely not.”

Click here to download AgFunderNews’ FREE report documenting the last 10 years in agrifoodtech!