Around half of all US agriculture production is within a 500-mile radius of St Louis, Missouri, including 80% of the nation’s soybean and corn crops. In recent years, the Midwestern city has also earned the name “the Silicon Valley of agtech” thanks to a bustling ag biosciences and agrifoodtech scene. Not only is the city home to big names like Bayer Crop Science, Bunge, and Post Holdings, it’s also a hub for entrepreneurs and startups tackling the biggest issues our food and ag systems face.

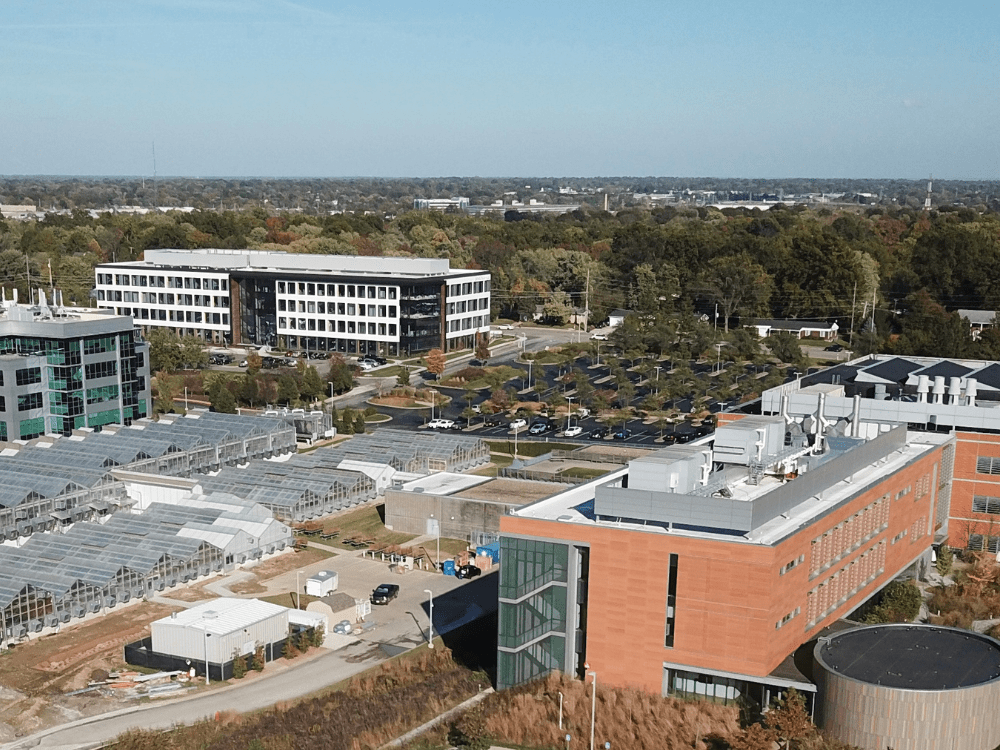

A pillar in this ag biosciences community is the BioResearch & Development Growth Park, or BRDG Park, a research park of ag and food tech innovators located on the campus of the Danforth Plant Science Center in St Louis’ 39 North innovation district.

BRDG Park helps early- to mid-stage agrifoodtech companies make the leap from research to commercialization, connecting them with new technologies, lab and office spaces, talent, funding, and other important relationships necessary to get products and services out of the lab and into farmers’ hands.

The region includes more than 1,000 plant scientists and 700 bioscience companies and hosts a number of events including AgTech NEXT, which convenes global players shaping the future of food.

Bridging the talent gap

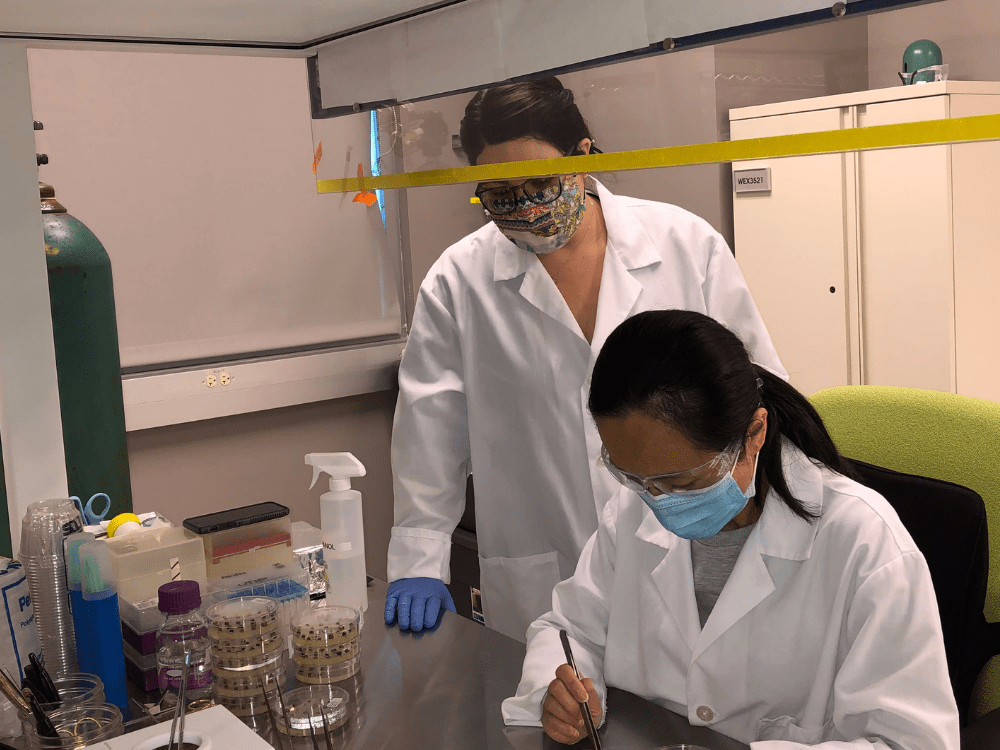

“Bridge,” as the community’s name is most commonly pronounced, is an apt name; as one of its most valuable offerings is the ability to foster connections between different companies’ innovators in order to move the ag and food tech industries forward. BRDG is also home to the St Louis Community College (STLCC) Center for Plant and Life Sciences biotechnician training program, which provides “skilled hands” at the bench and access to equipment through lab use agreements.

This access to people is what led Brazil’s Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira (CTC) to choose BRDG as the North American home for its research arm CTC Genomics.

Carlos Manuel Hernandez-Garcia, a cell biology discovery lead at CTC, says that his company, which focuses on sugarcane, initially considered Louisiana and Florida because of their proximity to farmers. “But we realized St Louis was much more advantageous, and one of the main advantages is access to talent coming from the universities, the Danforth Plant Science Center, and from other companies.”

Based in São Paulo, CTC applies genetic modification and genome editing to sugarcane varieties to improve traits such as drought tolerance and resistance to disease and pests. The company says it operates one of the world’s largest sugarcane germplasm banks, with more than 4,000 varieties.

While Brazil is one of the world’s leading producers of sugarcane, North America made more sense when it came to selecting a research headquarters for CTC. “Some of these [plant] traits will be done via genome editing and, at least conceptually, part of the early work will be done in St. Louis,” says Hernandez-Garcia. “Our breeding pipeline is for drought tolerance, for stress, for genomic data that is relevant here in Brazil, but access to talent to develop that technology was one of the great advantages of being in BRDG Park on the Danforth Center campus.”

Hernandez-Garcia notes that “all the other companies that could eventually be our partners” and the technologies they are working on are another important advantage. CTC Genomics is currently trying to sign a partnership with an unnamed company located in the same BRDG Park building. The company is also exploring the option to go public in Brazil and will likely also do so on the Nasdaq stock exchange.

“Having access to investors; having that branding in the US as a company, will be important here,” he says.

Relationships across the value chain

In addition to attracting companies from outside the region to St Louis, BRDG Park supports homegrown startups. Such is the case with CoverCress, a plant-breeding company that moved from the Helix Center incubator to BRDG Park in 2013.

CoverCress uses CRISPR gene-editing tools to develop a new cover crop derived from pennycress, which is native to North America. The crop provides farmers soil cover during the winter and early spring while simultaneously producing an oilseed that has biofuel applications. CoverCress has contracts with farmers that grow the crop on the company’s behalf; farmers get paid once the crop is harvested.

For CoverCress, the value of its crop lies in being able to crush the seed and extract both the oil and protein meal. CEO Mike DeCamp says that in order to do that CoverCress requires “partners and relationships that work well for us on crush” and can help off-take both the oilseed and meal products.

Because of BRDG Park’s proximity to the Danforth Center, college students, local venture investors, and customers, CoverCress has been able to build the relationships necessary to extract that value out of its product. DeCamp, himself a former executive at Monsanto, now Bayer Crop Science, says that over time the company has gotten help in the form of access to affordable lab space, greenhouse space, and other critical infrastructure thanks to relationships with the Danforth Center, startup incubator the Helix Center, and others in the 39 North district.

Notably, CoverCress has also garnered “buy-in from the entire supply chain” for its product thanks to these local relationships. Upstream, early investment from Monsanto Growth Ventures (now part of Leaps by Bayer) has enabled more development around gene-editing technologies. St Louis local Bunge Ventures, the VC arm of US agribusiness firm Bunge, has provided support in the midstream while REG Ventures, a subsidiary of US biodiesel producer Renewable Energy Group (REG), helps CoverCress tackle downstream markets.

CoverCress has since established a headquarters in 39 North, which DeCamp says has more than quadrupled its size, in addition to keeping lab space at BRDG and greenhouse space at the Danforth Center.

With the support of the ecosystem, CoverCress has evolved from having 100 plants at a Danforth Center greenhouse in 2013, to a planned 60,000 acres of commercial fields in 2022.