Rob Leclerc, PhD, is founding partner at AgFunder, the venture capital firm and parent company of AgFunderNews.

While Silicon Valley pours billions into artificial intelligence, a glaring disconnect is emerging in the trillion-dollar agriculture industry.

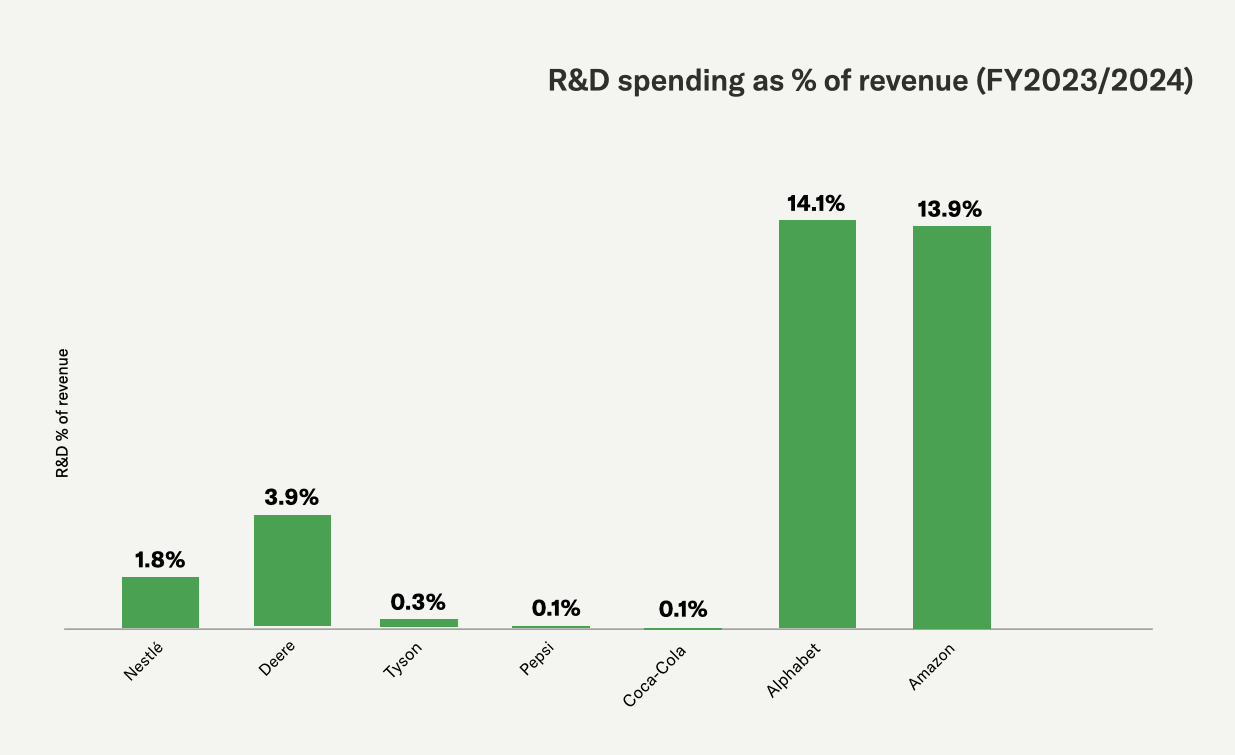

Incumbent agriculture giants invest less than 2% of revenue in R&D—a fraction of what tech companies spend—while clinging to aging assets and moving so slowly they suffocate the very startups they claim to court.

Market leaders are underinvesting in innovation even as the signals of technological transformation are unmistakable. That is the real story, not digital disruption. The numbers tell the story: when incumbents do acquire innovative agtech companies, their market caps often jump by billions, yet such acquisitions remain vanishingly rare.

Unless food and agriculture giants wake up soon, they risk becoming the next Blockbuster or Kodak; case studies in failure to adapt.

The investment gap is stunning

The most glaring evidence of strategic myopia is the size of research and development budgets. Alphabet spent $49 billion on R&D in 2024, roughly 14% of revenue. Amazon spent nearly $89 billion, about 14%.

Nestle, the world’s largest food company, spent just $1.9 billion, or 1.8% of sales. Deere, frequently cited as the agriculture industry’s tech pioneer, allocates roughly 3.9%. Tyson Foods spends less than one‑third of one percent. PepsiCo and Coca‑Cola report essentially zero R&D expenses.

The disparity extends to talent acquisition. Axios recently reported that Mark Zuckerberg is luring AI researchers to Meta with pay packages that can reach $300 million over four years, and even credible reports of offers as high as $1 billion for some researchers. That means big tech companies are literally renting a single AI scientist for more than the entire acquisition price of Blue River Technology ($305 million), Granular ($300 million), or Bear Flag Robotics ($250m) combined.

When individuals are worth more than the most successful agtech exits, it underscores how far the food and ag sector is lagging in its willingness to invest and pay for innovation. We saw this kind of ossification in pharma 20 years ago, but at least they outsourced R&D by shifting R&D budgets to M&A. Food and ag corporates aren’t even doing that.

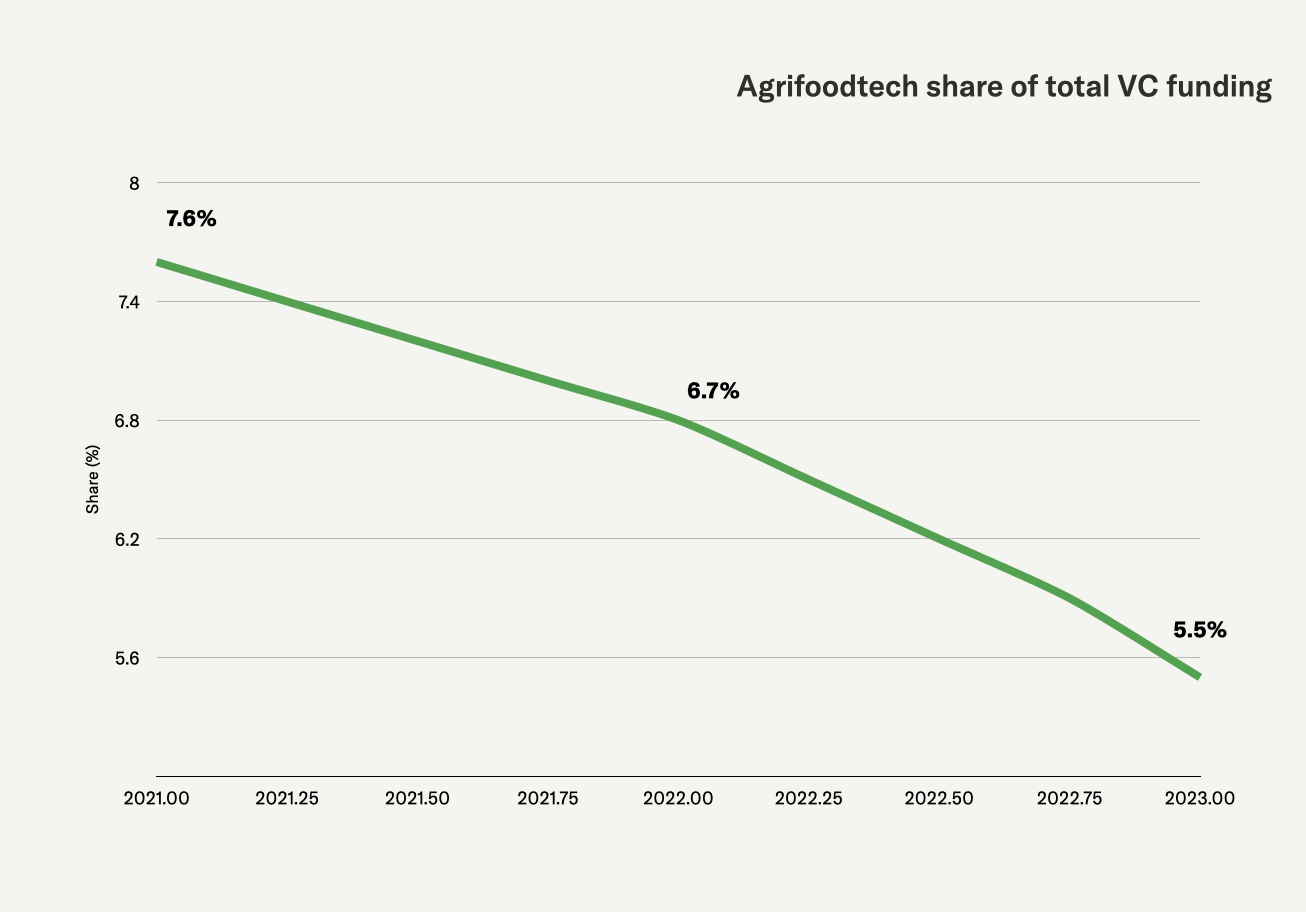

Venture capital tells a similar story. Global agrifoodtech investment peaked at $51 billion in 2021 but fell to $15.6 billion in 2023. Even at its peak, agrifoodtech represented only 7.6% of venture capital; by 2023 it had shrunk to 5.5%. Funding ticked up to $16 billion in 2024, but that’s still far below previous highs.

Most new dollars went into consumer-facing e-grocery companies rather than farm-level technologies, because investors see faster growth and less regulatory drag downstream. The agrifoodtech share of venture funding has fallen steadily:

Case studies: Good ideas suffocated by slow customers

It isn’t that startups lack ambition. The issue is that large food and agriculture companies treat innovation like a low-priority side project.

The graveyard of failed agtech startups reveals a deadly pattern: it’s not technical failures killing innovation, but the paralyzingly slow pace of adoption and decision making.

While tech companies can roll out products globally in weeks, agriculture giants operate on multi-year testing cycles that drain startup capital and kill momentum. This is more than just corporate conservatism. It reflects deep structural challenges unique to agriculture: seasonal growing cycles that limit testing windows, complex regulatory requirements, and the irreversible nature of farming decisions. But this caution has crossed from prudent to paralytic.

One ingredient company in our portfolio secured supply agreements with major global brands, yet after years of negotiations and dinky pilot demands, investors lost patience and the company filed for Chapter 11. The Poultry Exchange tried to bring transparent pricing to chicken buyers; founder Janette Barnard discovered that industry promises rarely translate into adoption, so she shuttered the business.

Abundant Robotics, which spent years and millions developing a robotic apple picker, collapsed in 2021 after failing to achieve market traction. TerrAvion offered aerial imagery to farmers; it declared bankruptcy in 2020 because capital demands outweighed adoption.

Vertical farming showcases the capital‑intensity trap: AeroFarms, AppHarvest and Planted Detroit have all sought bankruptcy protection, while Larry Ellison’s Sensei Ag shut down after greenhouse damage and poor connectivity. Freight Farms likewise liquidated in 2025 as its cloud service and customer support dissolved.

These failures share themes: customers say they want innovation but then balk at paying; partnerships drag on for years and big food and ag aren’t willing to lean in or put real skin in the game; and regulatory or contractual caution smothers momentum.

Make no mistake, these are technologies that will be mainstream one day, but there is so much risk aversion that no one is willing to step forward with any kind of conviction. Everything needs to be so de-risked that it’s no longer considered innovation. It’s a crisis of weak corporate leadership enabled by long tenured monopolies. But things are going to change soon.

Patent filings: outsiders are racing ahead

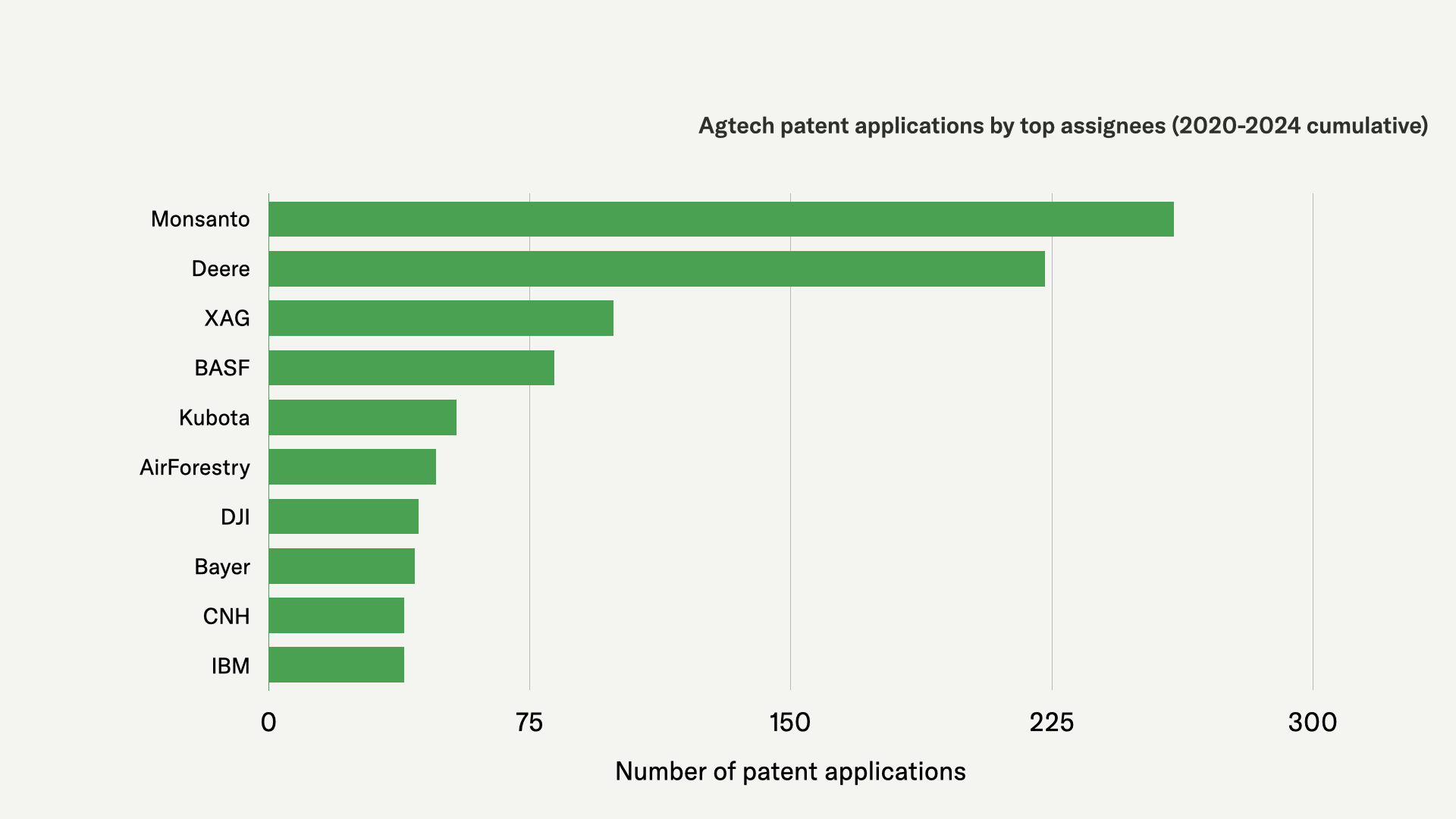

If incumbents aren’t spending on R&D, who is?

Patent data offer a clue. US agricultural patent publications tripled from 463 in 2020 to 1,433 in 2024. Monsanto and Deere still top the list, but Chinese drone maker DJI, Japan’s Kubota, Swedish forestry‑drone firm AirForestry, DJI and IBM are all among the top ten assignees. Outsiders are staking intellectual‑property claims in areas once considered core to agriculture.

This shift matters because platforms thrive on data network effects; the first player to aggregate data or secure patents can build insurmountable moats. Tech companies understand this dynamic. Traditional food and agriculture companies have become complacent and still think in terms of physical assets and linear supply chains.

Leadership: too few tech‑native executives

The cultural gap is also visible in the corner office.

Nestlé broke with tradition in 2016 when it appointed Ulf Mark Schneider from healthcare company Fresenius as CEO–hardly a digital disrupter. Coca‑Cola’s James Quincey holds a degree in electrical engineering, but spent his career in consulting and beverage operations. PepsiCo’s Ramon Laguarta has business degrees and decades in snack and beverage roles. BASF’s CEO Martin Brudermüller is a chemist who built his career within the company.

There are exceptions: John Deere’s John May served as CIO and led the Intelligent Solutions Group before becoming CEO. Tyson Foods temporarily elevated Dean Banks, a former leader at Alphabet’s X, to the C‑suite; the company noted that he brought “a unique skillset and background in innovation and technology”.

But these examples are rare. When you juxtapose Zuckerberg’s $300 million offers for individual AI scientists with the conservative R&D budgets and tech‑light leadership of most food companies, the talent exodus and absence of tech vision and leadership becomes inevitable.

Why would a world‑class engineer join a company spending 0–4% of revenue on innovation when a single hire at Meta earns more than an entire agtech exit? Even if they could match the pay, they still lack a compelling vision and deep commitment to innovation to attract top talent.

The market cap bump when incumbents do buy innovators

Yet investors seem to recognize that technology is the future for these companies.

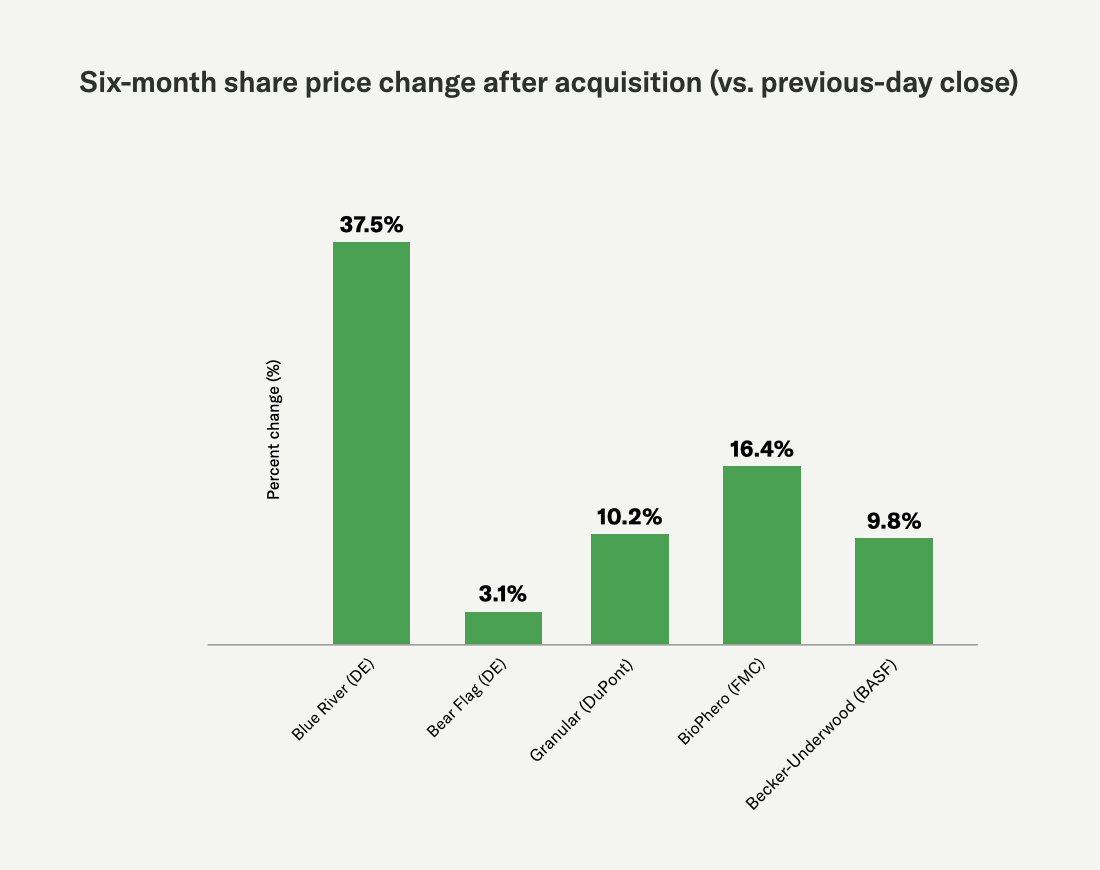

When John Deere bought Blue River Technology for $305 million in 2017, its stock jumped 37.5% over the next six months, translating to roughly $12.3 billion in market value; forty times the purchase price. Even more modest deals were correlated with material gains: DuPont’s added roughly $6.8 billion after the purchase of farm‑software maker Granular, BASF’s market cap grew by $4.2 billion after acquiring Becker Underwood, and FMC’s grew $2 billion after the acquisition of pheromone‑producer BioPhero. Raven Industries’ sale to CNH Industrial (+$2.5 billion) shows a similar pattern.

But perhaps the most important acquisition was Monsanto buying Climate Corp for $930 million in 2013. As one of our LPs (M.C.) reminded me, Bayer was internally valuing Climate at $6.5 billion during the Monsanto acquisition, and industry rumors suggested that Climate Corp was the lynchpin. Without this digital agriculture platform, Bayer wouldn’t have pursued Monsanto at all.

The key message is not that every acquisition yields a windfall. Rather, data suggests the market rewards companies that take technology seriously. A bar chart of the six‑month share‑price changes across major ag‑tech acquisitions makes this clear:

This pattern suggests that investors see these purchases as signals of strategic intent. A company shifting from a sleepy incumbent to an innovation leader. Yet since 2010 there have been only a handful of agtech acquisitions above $50 million, and a few are already buried inside corporate portfolios.

Why this matters

Food and agriculture are the largest sectors on Earth by employment and among the slowest to adopt digital tools. Climate volatility, labor shortages, and consumer demand for sustainability are breaking conventional models. Autonomous tractors, AI‑driven crop optimization, precision spraying, gene editing and distributed fermentation will reshape how food is produced and distributed.

Assets that were once moats—processing plants, fleets of trucks, brand equity—could become liabilities if data, AI, and automation-first platforms start to disintermediate supply-chains and manufacturing. Just look what Tesla did to the autoindustry, what SpaceX did to aerospace, and what Palantir and Anduril are doing to defense.

The risk isn’t that Big Food and Ag will vanish overnight. It is that companies that fail to build or buy data capabilities will gradually lose pricing power to those that do. As with taxis versus Uber or hotels versus Airbnb, incumbents will remain for a while, but value will migrate to platforms. Regulatory capture may delay the transition, but technology will eventually upend it. Slowly at first, then all at once.

Companies that’ve made deep commitments to innovation will have the insight, team, and culture to manage and thrive, while those that’ve been doing business as usual will fail. It’s happening in every other industry. There’s nothing special about food and ag that makes it immune.

What incumbents should do

Commit real capital to R&D. Spending 10–15% of revenue on innovation is common in software. Food companies don’t need to match that overnight, but doubling or tripling R&D budgets would signal seriousness and attract talent.

Create dedicated venture arms and acquisition funds. Stop writing one‑off cheques and start building a repeatable pipeline of acquisitions. The market‑cap gains speak for themselves.

Embrace platform economics. Invest in data infrastructure that spans farms, suppliers and consumers. Whoever owns the data will own the customer.

Recruit tech‑native leadership. Having a CIO in the corner office isn’t enough; boards should bring in executives who have real knowledge of AI, have built products at places like Amazon, Tesla, or Google and empower them to make bold decisions.

Adopt “fail fast” culture. Pilot projects should have clear milestones and kill criteria. Drawing partnerships out for years starves start‑ups and wastes corporate time.

Have a vision. When’s the last time a big food or ag company built anything inspiring? Identify some meaningful moon shots, plant a flag, ruthlessly chase them down.

Conclusion: wake up or get disrupted

Food and agriculture companies have enormous advantages including cash flows, brands, and distribution networks, but complacency is eroding them.

The data show a sector that spends a fraction of its revenue on innovation, files relatively few patents, and captures only a sliver of venture interest. Start‑ups that should help transform the industry are dying from neglect. Meanwhile, tech giants and nimble outsiders are quietly building the intellectual property, data platforms and talent pipelines that will define the next era of technology and outsiders will come for this industry.

The handful of incumbents that have made bold acquisitions have been handsomely rewarded by the market, proving that investors crave decisive action. As Meta’s $300 million recruiting packages for AI researchers illustrate, the price of innovation is rising fast, so much that one engineer now costs more than entire agtech companies.

The Great Disruption isn’t a future threat; it’s already underway. Companies can either invest aggressively and shape the future of food, or they can do nothing and become cautionary tales. The clock is ticking.

Author’s note: This op-ed was originally published in AgFunder’s quarterly investor update and I’m sharing it publicly at the request of several of our limited partners.