Editor’s Note: Hemendra Mathur is agribusiness investment lead and venture partner at Bharat Innovations Fund, a new $150 million early stage fund with a focus on agtech, cleantech, health-tech and enterprise-tech ventures. Mathur previously worked at SEAF India Investment Advisors and Yes Bank.

An estimated 450 million¹ of the population in India depends on farming for their livelihood. Agriculture in India makes for an interesting study with the farmer at the epicenter.

An interesting phenomenon of Indian agriculture is that it’s increasingly feminized with more women working in the fields while menfolk migrate to urban areas seeking alternate employment. Despite the increasing contribution of women to farming, few women have titles to the agricultural land in their name.

Landholdings are small and getting smaller. The average size of farmland holdings in India is also falling on account of the division of landholdings among siblings in each generation. Average holdings are currently around 1.2 hectares (3 miles) and widely expected to drop to one hectare or less. In fact, nearly 50% of Indian farmers have land holdings of less than half a hectare.

The Indian farmer has subsistence income and is heavily in debt. The average monthly income of the Indian farmer is a mere Rs6,400 ($100). An estimated 50% share of the income is from farming and animal husbandry (mostly cattle) while non-farming activities account for the rest. This income barely meets household expenses and leaves little for savings or investment in new farming techniques. Indian farmers on average have loans of over Rs47,000 ($700). Unsurprisingly, over 50% of Indian farmers are in debt, and a mere 10% have crop insurance cover.

Farming is not the preferred option to earn a living. Most Indian farmers inherited the farm from their ancestors. A significant one-third of farmers, according to various farmer surveys, are willing to quit farming if presented with alternate employment.

In this scenario, understandably, the farmer has limited ownerships of farming assets such as machinery. The penetration of tractors in India remains well below 10% — by comparison, the adoption of mobile telephones has surpassed 50% — and most small and marginal farmers lease land from larger farmers.

The Indian farmer requires assistance on several fronts including policy reform, infrastructure development, institutional financing and, more importantly, innovation to address some of their key challenges.

How Will Innovation Benefit Indian Farmers? Will Farmers Pay for Innovations?

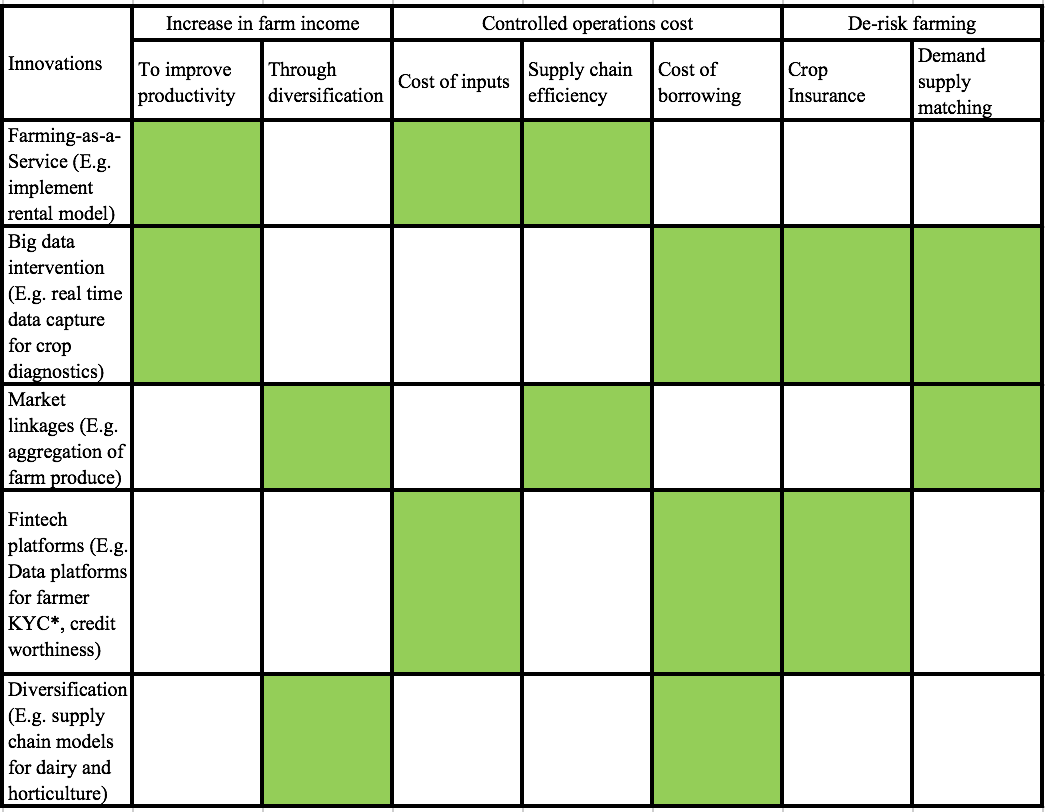

Agtech innovations can increase farmer incomes by improving the efficiency of farm operations, reducing costs, and de-risking farming considerably in the following ways:

- Improved productivity and diversification of farming activities.

- Optimizing the cost of applying inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, agrochemicals, mechanization.

- Improving supply chain efficiency and reducing the cost of borrowings.

- De-risking Indian agriculture by developing innovative crop insurance solutions and reducing supply-demand mismatch which causes price volatility.

Five agtech innovations that have the potential to collectively and comprehensively achieve the above are:

- Farming-as-a-service to make cost variable and make farming affordable to the majority of small and marginal farmers.

- Big data intervention through real-time capturing and synthesis of data to aid farmers in better decision making.

- Market linkages for the sale of farm produce to facilitate disintermediation and aggregation of farm produce so farmers reap a higher share of the end-consumer price.

- Fintech platforms to aid institution financing to reduce the cost of borrowing for farmers.

- Diversification to increase the sources of income for farmers.

Figure 1: Role of Agtech Innovation Mapped with Farmer Needs

Each innovation in Figure 1 addresses at least three pain-points for Indian farmers. Indian farmers have time and again demonstrated an eagerness to set aside convention and adopt new practices, as demonstrated by the following three key developments in Indian agriculture in the past decade.

- Small and marginal farmers are taking horticulture to new growth levels – in 2016 they produced approximately 290 million tons compared to less than 150 million tons in 2006. They are doing this as it fetches higher/additional income and is less working capital-intensive.

- Many farmers are using new equipment like a rotavator, a machine that breaks up the soil for planting, laser land levelers, solar-powered irrigation pumps. Those that cannot buy the equipment are renting it, even using social media for bookings!

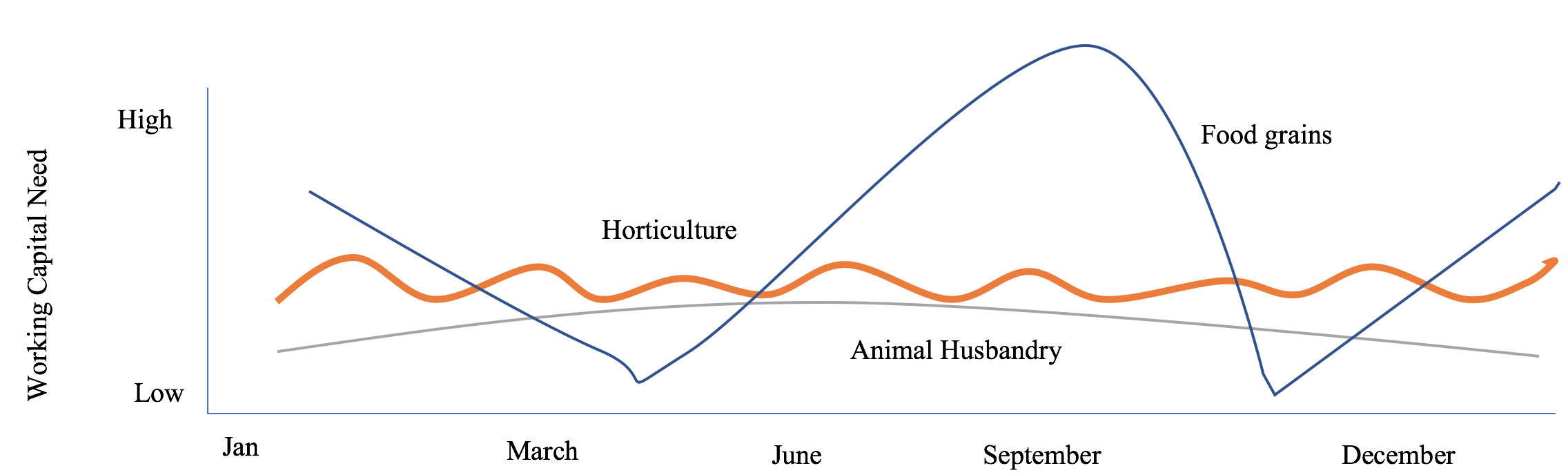

- Growth in the cattle, poultry, and aquaculture feed markets in the past decade – they now have a combined size of $ 18-20 billion. This is a clear indicator that animal husbandry has been adopted to diversify income sources, improve the working capital situation (refer Figure 2) and allow for non-farming income from alternative sources in drought years.

Figure 2: Schematic of a Farmer’s Working Capital Requirement During the Year

As demonstrated in Figure 2, in the case of food grains, farmers enjoy liquidity only twice a year – at harvest time of Rabi (April-May) and Kharif crops (October-November) respectively. Horticultural crops (read vegetables) offer more frequent liquidity due to the short lifespan of those crops. Animal husbandry (read dairy) offers the best liquidity of all because surplus milk is sold for cash daily with winter months yielding better than summer due to the availability of better fodder resulting in higher milk output. Both horticulture and animal husbandry have demonstrated significant easing of working capital requirements for farmers and this has promoted the higher adoption rate of these farming activities.

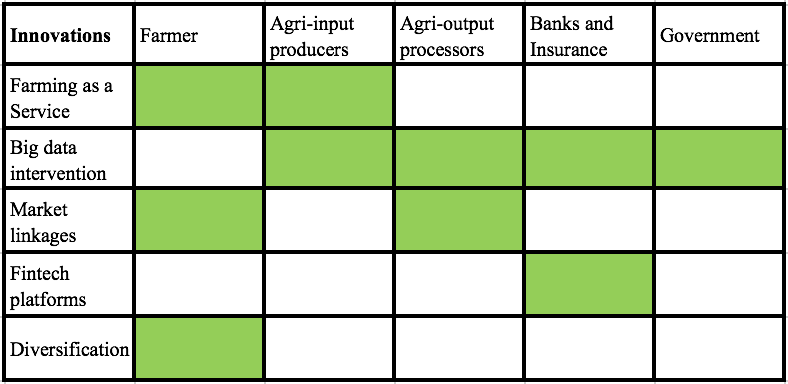

Given the cash-strapped financial status of the farmer, the cost of the innovation will need to be financed by other constituents in the supply chain. The likely buyers of agtech innovations who stand to gain from it, and are therefore willing to finance the costs, are mapped in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Likely Buyers of Agtech Innovations in India

Farmers have demonstrated willingness to pay for innovations that have immediate tangible benefits; be it hiring of implements or farm produce aggregation for a better price and higher income through diversification.

This also implies that entrepreneurs working on agtech innovations must prepare themselves for sales through a B2B business model for the initial period of sustenance.

Four Recommendations to Facilitate the Adoption of New Innovations by Farmers

- Rural Incubation Centre: The Government of India entrepreneurship fostering initiative, Atal Innovation Mission, provides grants of up to Rs100 million ($1.5 million) to each center, but should give preference to incubator centers set up in rural areas and targeting agriculture innovation.

- Rural Entrepreneurship: Agriculture alone cannot provide a sustainable living for India’s teeming rural youth. Rural youth will not be tempted to migrate to urban areas for employment if they are provided with entrepreneurship opportunities in the villages. These opportunities can center around services that are in high demand such as aggregation, farm produce storage, soil scanning, implement rentals and cattle feed centers.

- Village Data Hubs: Farming decisions are taken based on previous years’ data but the availability of real-time and accurate current year data is limited. Institutionalizing farmer advisory services through village data hubs will help capture real-time data from in-field interventions such as drones, sensors, IoT and satellite images, with access of this on smart phones which are today affordable. Innovations should drive real-time capturing and analysis of the data and the disaggregation of data at the farm level.

- Village Adoption by Research Institutions: Simple mechanisms to transfer technology from research institutions and agricultural universities to farmers; and incentives for institutions to adopt clusters of villages to facilitate “faculty-researcher-student-farmer” interaction, will provide much-needed support to the farming community. The village adoption program of National Institute of Food Technology, Entrepreneurship and Management (NIFTEM) in India, trained farmers in some food technology innovations, for

In conclusion, there needs to be a concentrated effort from investors and innovators to develop and deploy innovation to make farming an aspirational profession in India.

As Will Rodgers wisely said, “The farmer has to be an optimist, or s(he) wouldn’t still be a farmer.”

¹The population in India is an estimated 1,326,801,576. Of the over 167 million rural households in India, approx. 90 million households are engaged in farming. The average farming family has five members, thereby near 450 million people directly dependent on farming.