The well-documented potential for drones to revolutionize agriculture reached fever pitch in 2015.

The robotic technology captured the imagination of investors, entrepreneurs, and farming businesses alike as a means to take over certain tasks on the farm and play a role in ‘precision agriculture’ — the modern farming technique aimed at making production more efficient through the precise application of inputs and machinery.

The promise of drones mainly centered around crop scouting through imagery captured by the drone, but also around applying inputs such as pesticides.

During 2015, drone technology companies that identified agriculture as an industry of focus raised $326 million in venture capital funding. That was a 189% increase on 2014, according to AgFunder data.

The startups that raised funding in 2015 were split broadly into two categories: the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) manufacturers and the drone software platforms mapping out flights and providing some analysis on the images received. Some did both.

(For the purposes of this article, I am going to focus on drone technologies providing crop scouting insights from imagery. There are fewer companies innovating around input application from drones at the moment, although this space is certainly not without potential.)

But towards the end of the year, there were signs that expectations for the technology in agriculture may have been inflated. One potential indicator of this could be the 64% drop in funding in 2016 to $118 million. But, more importantly, the signs also showed in the agriculture community.

In the early days of using drones to capture aerial imagery, just having an aerial image of your farmland added great value. The idea was that farmers could fly their fields as often as they wanted to pinpoint issues, such as irrigation leaks, leaf color variation, or pests like nematodes. Soon, however, this information was not enough and farmers complained they were getting less and less value out of the images. While the images could help them plan out their days better by highlighting where these issues were occurring, an argument was forming that by the time the imagery told them about certain issues, it was often too late to remedy the situation.

Grower Demands Changed: ‘Give Us Actionable Intelligence!’

“Two years ago, to be frank, showing growers and agronomists pictures was enough and it was easy for us to start with; so in year-one [2015], we had an image-focused product,” says Eric Taipale, CEO of Sentera, the two-year-old startup from Minneapolis. “There is definitely value in just the images. When corn is seven to eight feet high, no-one can cover the whole field on foot, so we could take a picture and farmers could see weeds and areas that weren’t growing well. But it was also because people hadn’t had these tools before.”

Growers soon wanted more from their images and the term “actionable intelligence” has become popular among startups and investors relating to the technology.

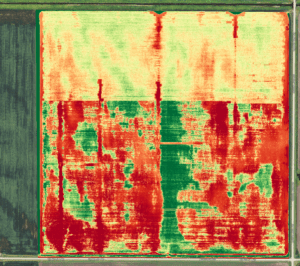

The first step in providing this actionable intelligence was producing crop health maps for farmers to pinpoint areas of potential yield loss. The way to do this is by measuring the amount of biomass or live green vegetation in the crops. Near-infrared (NIR) sensors can detect vegetation levels based on the amount of light reflected off the leaves — the higher the biomass content, the more light that’s reflected. Drones startups starting measuring these vegetation levels using the Normalized Differentiation Vegetation Index (NDVI), a simple graphical indicator for these measurements, to produce what are commonly called NDVI maps. These maps show crop health through colors, which vary from bright green for areas with most vegetation to red for the least healthy areas.

Agribotix, which was founded in Colorado in 2013 as one of agriculture’s first drone startups, produces NDVI maps for its clients including Jamie Dumalski, a Canadian farm operator who manages 35k acres of peas, lentils, canola, wheat, barley, and soy for a farmland investment group in Saskatchewan.

Dumalski is a drone enthusiast. He flies his own drones and sends the images to Agribotix, which sends back the NDVI images. He covers every inch of the land he manages every three days, which means he’s able to spot any small changes in the NDVI maps. Last year, he said he saved 17% of his pea crop after using the images to detect an aphid issue and spot spraying in the appropriate places. “That more than paid for the drone,” he tells AgFunderNews.

Dumalski is very proactive, and there are many others like him, such as this sugar beet farmer using DroneDeploy. Another early drones-for-ag service, DroneDeploy is a software platform offering a similar NDVI mapping service as well as helping farmers to plan and automate their flight paths.

The process of launching, flying, and processing imagery seems to work for Dumalski, but it doesn’t for other farmers and agronomists who complain that they’re impractical and inefficient, and Dumalski sees his peers flying their drones less frequently, and often getting information back too late to stop crop damage and yield loss.

The Challenges

The limited battery life of current drones making it hard to cover large properties, and the regulations requiring the drone to always be in the visual line of sight of the pilot, are two common complaints. But largely the problem many have is the time and cost of deploying the technology, and then in processing it to glean insights.

Many early drone technologies for agriculture have relied on uploading images to the cloud for processing or even returning to a PC to upload and then push through to an analytics program to create the NDVI maps. With limited cellular coverage in many agricultural regions, and large distances to travel between fields and the office, farmers and agronomists have complained that this can become an arduous process. And, without the benefit of real-time, actionable insights in the field, many believe the tech is not worth the time and cost.

“Farmers and agronomists need to be able to act upon the information delivered by these systems in a way that shows a tangible return on investment,” Ewan MacFarlane, head of digital agronomy at Origin Enterprises in the UK tells AgFunderNews. “For that, it needs to be made available to them at the time and place that it is needed.”

These uncertainties pushed some existing startups focused on the sector to improve their services. It also pushed some out of the industry altogether — AirWare, Skycatch and CyPhy are three drone technology companies that once appeared to target agriculture but have now removed the industry from their websites as a focus area.

“Now customers expects us to deliver highly precise analytics that automatically detect problems and gives prescriptive action immediately. We are not just providing 500 pictures, but providing an answer,” said Sentera’s Taipale, who recently released a new feature to its service, the NDVI Toolbox, which enables users to detect changes at a more granular level through customizing how they view their maps.

What is the Next Wave of Drone Technologies for Agriculture?

The commoditization of drones, which can now be purchased for as little as a few hundred dollars, has also made the actual vehicle for flying of less importance; now it’s all about the sensor attached to the drone; the processing and analysis of that imagery, and the real-time, actionable insights that analysis can give to farmers.

Here is a selection of startups you may not have heard of to highlight how drone technologies for agriculture are evolving to resolve some of the painpoints discussed above and add more value to the industry.

Next Generation Drone Sensors

SlantRange is a drone sensor manufacturer and imagery analytics provider using computer vision. It recently announced a new multispectral sensor called the 3p. One of the main benefits of the 3p is its on-board image processing and in-field analytics capabilities, which can give farmers instant insights in the field, without the need for cellular connectivity and cloud connection.

“Much of the industry relies on cloud-based processing systems which are inaccessible for most of the world’s agricultural lands,” says Matthew Barre, director of strategic development at SlantRange, adding that on-board image processing and in-field analytics increases the addressable market for drone-based systems more than 25 times.

Combined with new and more efficient algorithms for data aggregation in the startup’s software platform SlantView, the 3p sensor can provide quantitative metrics about the status, health, and yield potential of crops immediately after a drone flight.

Built around Qualcomm’s Snapdragon Flight platform for drones, the sensor uses spectral imaging and computer vision techniques to look at the spatial patterns of growth in crops, weeds, dead vegetation, and bare soil, and to isolate the crop plants from the weeds and the background. It looks specifically at the color of the plant, how it’s growing and what patterns it’s following, focusing on green vegetation and subtle changes in color to detect changes early enough before it’s a problem.

SlantRange also carefully calculates the contribution of sunlight in images to eliminate that from any of the measurements, which Barre argues sets it apart from others.

“If you don’t correct for weather and lighting conditions, results will be meaningless,” Mike Ritter, CEO told AgFunderNews last April, because weather conditions will impact the results.

SlantRange says it has been able to detect failed irrigation systems, classify vegetation types, characterize and count individual plants, and detect specific pest infestations.

“The one-size-fits all of “NDVI” has been proven to be of limited utility,” said Barre. “The high-resolution data available from drones can be used for much higher value information products, for example plant counts and the separation of weed and crop populations.”

Gamaya, which we’ve written about before, is also a drone sensor and analytics platform. It differentiates itself by manufacturing hyperspectral sensors; the majority of drone imagery companies use multispectral images. The novel design can show over 40 bands of light instead of just the four — red, green, blue, infrared — provided by multispectral cameras. By capturing over 40 bands of light instead of just four, hyperspectral can detect specific physiological traits within the plant, argues the startup. The sensor is Gamaya’s enabling technology, however, and it says its main intellectual property is in its analysis of this hyperspectral imagery using artificial intelligence to produce information about the plant’s physiology. (Read more about Gamaya, which won an AgFunder Innovation Award, here.)

Advanced Imagery Analysis Using AI

Hummingbird is a drone-enabled data and imagery analytics company leveraging machine learning and crop science. The UK-based startup offers 10 flights per growing season to detect weeds and disease at key times during the growing season to help farmers decide what and how much input to apply. It promises a 24-hour turnaround after each flight. It also offers yield prediction. Hummingbird is drone-agnostic, but mostly uses senseFly and Parrot drones and sensors. The startup layers satellite imagery and soil maps over the drone imagery as well as combine harvester reading for yield maps, and “any bioinformatic map we can get our hands on,” says Will Wells, CEO of the company.

“What agtech companies consistently get wrong is providing black and white, generic observations which are superficial and annoy farmers; they are not decision support,” he said. “Hummingbird is giving farmers research and data-backed information about what’s happening in their fields in time for them to act on it. We take it all the way up to prescription.”

Wells believes Hummingbird’s approach is the obvious next step for drone technology in agriculture.

“We watched the drone space for a long time and we figured out it was the sensors, and then that it’s really about the analytics using artificial intelligence and machine learning. Fundamentally we’re an artificial intelligence company with drone as a mechanism. If we were just a drone company, that would not be enough. In that sense, we are a symptom of the decline in efficacy of drones in agriculture, an antidote to their standalone limitations,” said Wells.

Crop science is a core part of Hummingbird’s offering and it has partnered with a range of UK research institutions including NIAB. The pilots that perform the flights for the company are also trained agronomists, which has helped it to refines its algorithms as they’re flying and groud-truthing at the same time.

IntelinAir is also using machine learning to analyze aerial imagery as a service, although it acquires this imagery through third parties. Al Eisaian, CEO of the company, argues that for large corn and soy acreage, it’s only practical to use plane imagery, flying at around 2500 feet altitude with specialized sensors to get a 15cm resolution. For high-value crops or for spot-checking problem areas pointed out by its analytics software, the company employs third parties to fly drones over the land for images with a 5cm resolution. Using computer vision, the startup aims to find anomalies that could have an adverse effect on a farmer’s operations and profitability, such as a weed infestation, nutrient deficiencies, weather damages, or insects and fungus. (Read our Q&A with AgFunder Innovation Award winner Eisaian here.)

Combining Data Types

Mavrx, which first based its insights on aerial imagery from planes, recently added a drone scout feature to its app to create specific drone flight maps for farmers to assess potential problems areas identified with its ultra high-resolution imagery from planes. The idea is to help farmers locate fields where yield is at risk efficiently to eliminate the burden of drone-based image processing, according to a blog post from Mavrx at the time of launching the new service.

“We’re making it possible for experts to remain in a central location to diagnose and direct actions across a large number of fields over a broad area,” wrote CEO Max Bruner in the post. “Time is saved by having scouts drive to the field locations where the drones launch themselves, fly to the areas of interest, and upload geotagged images to their Mavrx account. This allows real-time action to be taken to resolve issues while they can still be addressed. We want to make field visits as fast and effective as possible.”

Mavrx combines satellite, aerial and drone imagery to offer farmers guided scouting and sampling, based on alerts, grids, and zones. It also offers nitrogen prescriptions, and crop performance benchmarking based on its own Field Velocity Index computed using five years of satellite and crop data to help farmers monitor the impact of their management decisions versus the effects of rainfall and growing degree days. It also creates management zones for farmers to manage in-field variability by detecting patterns.

Resson is an aerial image analytics company that uses computer vision and machine learning techniques to detect and classify in-season biotic and abiotic stressors such as plant disease, insect damage or water shortage. The Resson Agricultural Management & Analytics System (RAMAS) takes in imagery from multiple platforms, including ground-based cameras and UAVs, to perform these analyses, moving beyond NDVI. It detects and localizes anomalies allowing growers to follow individual plant growth and make in-season course corrections.

“What seems to be missing from today’s drone data service providers is the expertise to interpret the data, “ground truthing”, and recommend a course of action,” says chairman Jeff Grammer.

PrecisionHawk recently partnered with A&L Canada, the agronomy lab, to integrate A&L’s ground sampling data with PrecisionHawk’s drone imagery. “We believe that farmers are more demanding and sophisticated than ever,” said Thomas Haun, senior vice president at PrecisionHawk, another early player in the ag drones space. “They want the dots connecting about why something is happening in the field, and pure aerial images lack context. We’re now moving from pictures toward data and analytics.”

Are you a farm operator or agronomist that’s experimented with drone technology? What were your experiences? Email [email protected]