Bathtub brew. Snake oil. Bugs in a jug. For years, companies developing biologicals — a form of crop protection derived from naturally occurring substances like microbes, peptides, and plants — have labored under the shadow of these labels, often with justifiable reason.

The Green Revolution of the twentieth century brought massive increases in crop yield thanks to, among other things, synthetic chemicals and fertilizers as well as genetically engineered seeds (“GMOs”). Lower food prices and a reduction in global poverty followed; some studies have shown that without the Green Revolution, “caloric availability” would have declined by roughly 11–13% worldwide.

But concerns around the planetary impacts of synthetics are almost as old as the Green Revolution itself. (See Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring, widely considered instrumental to the growth of the environmental movement.)

Soil degradation, biodiversity loss, infamous “dead zones,” and numerous human health conditions are all linked to chemical crop solutions. The United States Environmental Protection Agency’s most recent list of “banned” pesticides, for example, stretches 43 pages long — and lags in comparison to restrictions in other countries.

One of the promises of biologicals is that they can reduce the usage of chemical inputs, potentially protecting ecosystems and, in an age of rising input costs, growers’ wallets. Furthermore, in recent years, weeds and insects have become more resistant to herbicides and pesticides thanks to the overuse of chemicals over a long period.

There may too be a legal case for biologicals. Agrochemicals giant Bayer, for example, has fielded one lawsuit after the next since buying Roundup creator Monsanto in 2018; at last check, Bayer had yet to resolve more than 100,000 cases and called the ongoing litigation “a huge burden” on company financials.

Yet for all their promise of costs and environmental savings, the biologicals sector facing ongoing challenges in 2024. CropLife’s 2024 Biologicals Survey found that nearly half of all respondents cited “a lack of trust in product performance” as the number one reason for lagging adoption rates, followed by cost. The bugs in a jug stigma, it seems, is as resistant to death as houseflies eventually became to DDT.

“Snake oil and bugs in a jug are going to be with us for a while,” Walt Duflock, VP of innovation at Western Growers, tells AgFunderNews. “It’s got credibility out there in the marketplace. Folks in the biologicals space have to just run with that and run past and around it.”

In 2024, figuring out how to do that is top of the agenda for startups, scientists, advocates, and many others hoping to integrate biologicals into more of US agriculture.

Biologicals basics

The term “biologicals” is a bit like “regenerative agriculture”: it has no single definition and is a rapidly expanding sector. Ergo, the category is tough to define, let alone get everyone to agree on a single set of sub-categories.

Or as The Mixing Bowl puts it, “The biologicals industry is a messy word salad.”

That becomes doubly true when one starts to break down the sector’s various categories, which are also rather fluid. The most commonly cited ones are biocontrols and biostimulants.

As the name suggests, biocontrol products protect crops in the form of biopesticides, bioherbicides, biofungicides, etc. They target pests, weeds, and fungal and bacterial pathogens. They can be used in place of chemical pesticides or with them as part of an integrated pest management (IPM) program. Typically, these products are subject to EPA regulations.

Biostimulants enhance plant growth and productivity. Biofertilizers, microbial inoculants, and plant-growth regulators are some examples of biostimulants. Unlike biopesticides, some biostimulants may not need to be registered with the EPA, though as discussed below, this is changing.

Some groups, including the Biological Products Industry Alliance, class biofertilizers as their own category.

The biologicals market in 2024

Between 1960, when the Green Revolution was in full swing, and 1990, an average of just three new biologicals debuted to the global market each year. That number jumped to 11 between 1991 and 2016.

Meanwhile, CropLife’s survey found that 72% of respondents “are planning to increase the number of biological products their companies sell to grower-customers during the coming year”; this number dipped slightly from 74% in 2023.

Biostimulants are the most common biological products, according to the survey, in which 83% of respondents said they sell these products to their customers. Biopesticides showed “an uptick in applications,” growing to 22% in 2024 from 19% in the 2023 survey. Respondents selling biofertilizers dropped to 41% in the 2024 survey versus 50% in 2022-2023.

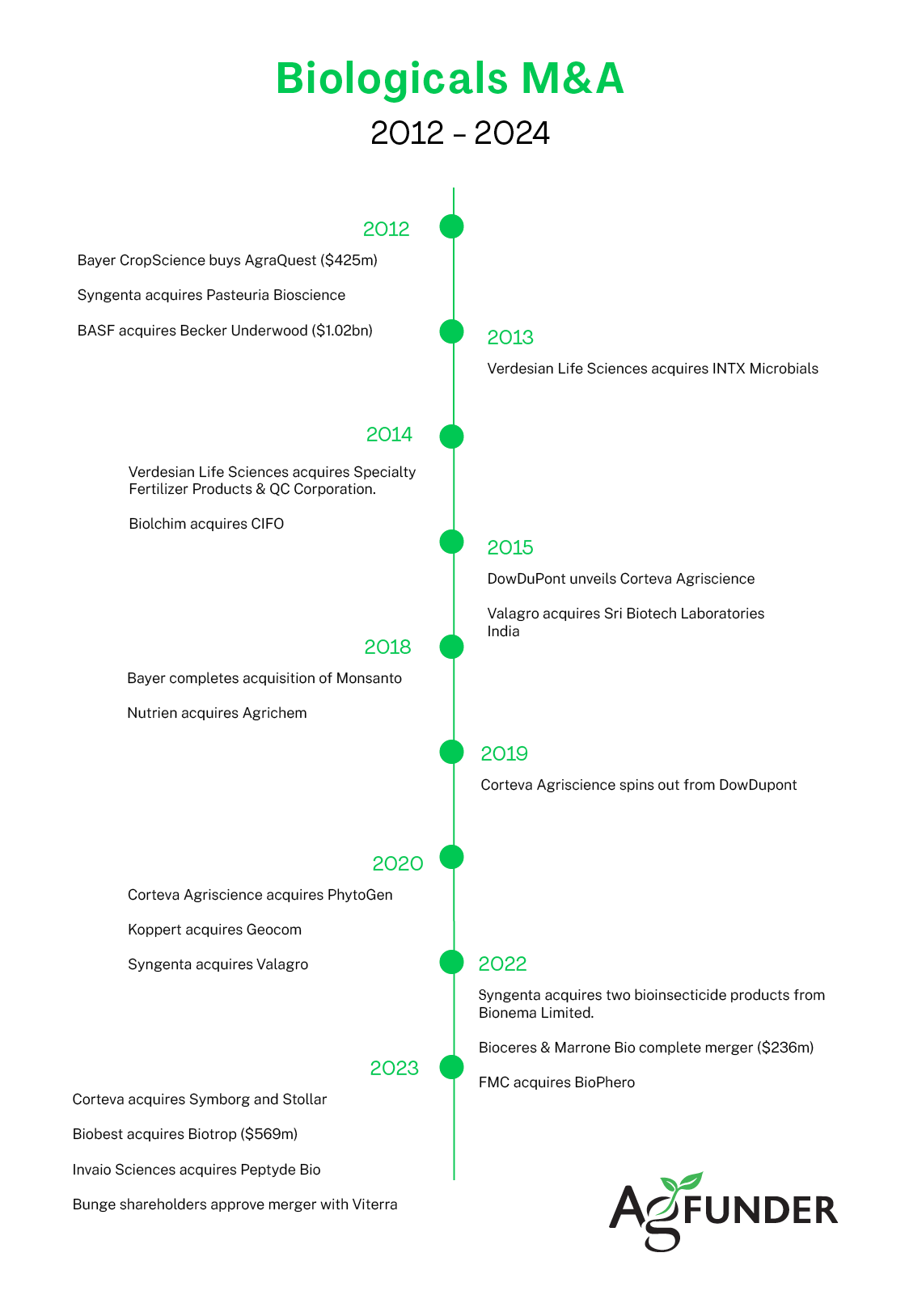

All the major agrochemical companies, including Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta and BASF, now have departments dedicated to biologicals, and have collectively made many acquisitions in the space over the last decade.

The US market today also includes a host of startups. To name just a few: Pivot Bio was one of the first companies to debut a nitrogen-fixing solution, New Leaf Symbiotics, which makes biostimulants, and AgroSpheres, known for its novel bioencapsulation technology.

The investment landscape

Biologicals is a tough market to invest in, says Rob Leclerc, founding partner at agrifoodtech VC AgFunder. [Disclosure: AgFunderNews’ parent company is AgFunder.]

He notes that while AgFunder has invested in a couple of biologicals startups in the past, there are several things that make investing in the space difficult.

“The mode of action [the way in which active ingredients eliminate their target] is often difficult to characterize, which makes [a startup’s] sales process very hard. Farmers really want to understand that mode of action.”

Another longstanding challenge, he says, is the variability of performance in different environments, which “makes it very difficult to have a lot of confidence in what is going to happen.” In other words, it’s tough to prove the product works in various types of fields and growing scenarios across various crops.

Distribution of these products adds another complication to the stack. “Even when you find a distribution channel, the big guys can cut your legs out under you and then who do you sell your company to?”

Nonetheless, startups continue to proliferate in numbers.

Top venture capital deals for biologicals startups since 2013 reflect the broad nature of the category. Data from AgFunder Research includes everything from renewable fertilizer (Atlas Agro) to biostimulant-maker New Leaf Symbiotics and enabling technologies from the likes of fermentation tech company Locus.

Top biologicals rounds 2023

| Date | Company | Amount | Stage | Lead investor |

| 2021 | Pivot Bio | $430m | D | DCVC, Temasek |

| 2023 | Locus Fermentation Solutions | $117m | Debt | Jeffries |

| 2021 | AgBiome | $116m | D | Blue Horizon, Novalis LifeSciences |

| 2021 | Anuvia Plant Nutrients* | $103m | C | TPG, Pontifax AgTech |

| 2020 | Greenlight Biosciences** | $102m | D | Morningside Ventures |

| 2018 | Joyn Bio | $100m | A | Bayer, Ginkgo Bioworks |

| 2020 | Pivot Bio | $100m | C | Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Temasek |

| 2022 | Vestaron | $92m | C | Ordway Selections, Cavallo Ventures |

| 2021 | Invaio Sciences | $88m | C | Flagship Pioneering |

| 2019 | Provivi | $85m | C | Pontifax Global Food |

*Anuvia suspended operations in 2023.

** Disclosure: AgFunderNews’ parent company, AgFunder, was an investor in Greenlight Biosciences.

‘We’re upping the game’ for biostimulants

But back to the bathtub brew.

Pam Marrone, a serial entrepreneur and one of the original trailblazers for biologicals, started the Biological Products Industry Alliance back in 2000 in part to address the bugs-in-a-jug stigma. (The group was originally called the Biopesticide Industry Alliance and focused on that area.)

She suggests this stigma stems from a combination of lackluster products and, particularly in biostimulants, a lack of regulations.

“The snake oil perception of biopesticides is less so than with biostimulants because [the former is] regulated,” she says. For example in California, if a company wants to get registered, it has to present rigorous field trial data.

Biostimulants are another matter, she says. “The products have gotten better, but we still have that lingering perception with biostimulants because the barriers to entry are so much lower than for biopesticides,” she says.

As a result, “There are companies out there that are mom-and-pop companies that survive but are literally bugs in a jug. You don’t know what quality they have. They work. They do boost the plant.” But quality control remains an issue.

By way of example, she mentions a company that claims to be testing on 500 microbes but is only doing PCR quality control on 10. “You can’t claim the benefits of 500 microbes if you’re only doing PCR on 10,” she says. “And first PCR is only going to tell you what you know; it’s not going to tell you what you don’t know. What about your human pathogens? There’s no human pathogen testing required [for biostimulants].”

When Marrone and colleagues launched the Biological Products Industry Alliance, any member that joined had to sign a “pledge of product quality” and ensure their marketing claims met the label claims.

The Alliance still maintains the same standards today and has begun to hold biostimulants to the same rigor it laid out for biopesticides 20 years ago.

“We’re upping the game and demanding just like we did for biopesticides all those years ago,” says Marrone. “‘Sciencing up’ the industry is really critical to give everyone the credibility of these products.”

A matter of correlation vs causation

Western Growers’ DuFlock, who comes from a fifth-generation farming family in California, says one of the issues is that biologicals simply have a higher proof burden than other sectors of agtech. After all, no one’s ever applied the label “bugs in a jug” to a weeding robot, he says.

“When you run a laser weeder down a row, you’re going to see what happened, and it’s going to [perform] most of the time. That’s not the case with biologicals. We hear the story in biologicals all the time: ‘Well, we put it in the ground, we ran the trial, it seemed to do well. Then we bought it, put it on the next crop and it didn’t work at all close to what it was supposed to.'”

Biologicals startups face what DuFlock calls “the problem of correlation versus causation.” In other words, a company can prove resistance to, say, aphids, but may struggle to prove that their product caused that resistance.

Changing the science of biologicals

Recent technological and scientific developments could go far in this quest for causation, particularly when it comes to efficacy. Unlike chemical inputs, biologicals are far more susceptible to environmental factors that can hamper products’ ability to get the job done.

However, science has changed rapidly and drastically in the last 20 years, says Marrone. “We didn’t have inexpensive gene sequencing back then.”

“The full gene sequencing and microbiome analysis of soils before and after treatment with biological products, and just the gene sequencing really, makes a huge difference.”

For example, one of her companies, Marrone Bio (now called ProFarm Group), has a product called Venerate developed from a new species of Burkholderia (the name for a group of bacteria found in soil and water).

“By doing gene sequencing, we know what the main metabolites are and [can] amp them up by 500 fold. We were able to drop the pharmacy treatment from six ounces per acre to less than an ounce, making a better product that’s almost like a chemical product.”

The next generation of Venerate is currently undergoing the regulatory approvals process with the EPA.

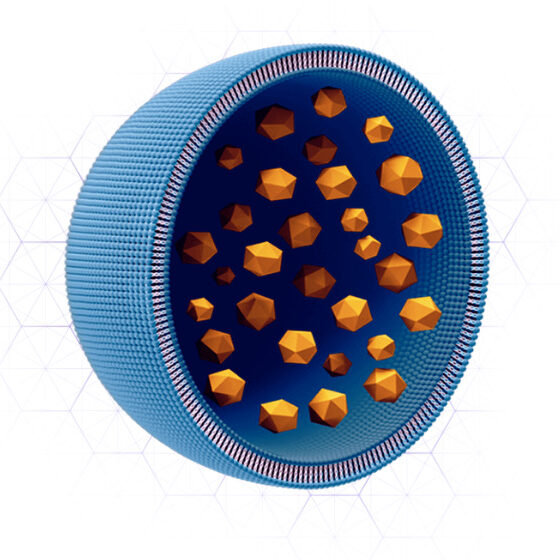

The AgroSpheres encapsulation allows for natural added stability and a tunable release profile in products. Image credit: AgroSpheres.

On the formulation side, there are new ways of encapsulating solutions that can preserve them and make them last longer.

Case in point: AgroSpheres has a technology that forms a protective shell around the RNA, physically shielding active ingredients in a pesticide from environmental pressures.

“Our technology allows for manufacturing, encapsulation and delivery of that biological pesticide all in one platform,” AgroSpheres cofounder and CEO Payam Pourtaheri tells AgFunderNews.

“The technology and the platforms for building these microbials are getting better,” says DuFlock, who adds: “The tools to help measure the results and identify costs are getting better. We can do a lot more with soil testing. We can do a lot more with water testing, with stress testing. On plants, we can do a lot more with genetics than we ever have, and measure some of that.”

“The ability to prove causation only increases as we can track more stuff accurately and all the way through. That will only continue to improve.”

‘Farmers need to be assured’

All this science needs to be communicated to farmers and growers for the market to have any real traction.

This has been a problem for years. A well-known Farm Journal Pulse poll found that almost half of farmers (41%) say they need to know more before using biologicals products. At the same time, 35% surveyed said they see potential in using biologicals — if the industry can manage to get the bathtub brews out of the market.

Pivot Bio, in large part, attributes its success in the biologicals landscape to its relationships with growers.

“We [initially] worked very closely with some trusted growers that we had in our network, and we didn’t charge for the product,” says Mitchell Craft, sustainability, executive, and corporate communications leader at Pivot.

“We basically went out with a 30,000-acre trial and it performed incredibly well. Then we began building out our sales network, and that go-to-market strategy is I think what helped to build that trust with the growers.”

Pivot opted to work with independent reps versus traditional distributors.

“These independent reps have very close relationships with growers, so we were able to work with them hand in hand and bring them along on the journey so that those early adopters who were interested got a really customized experience,” says Craft.

“By having over 1,000 independent reps who are selling the product and have one-on-one connections with growers, we’re able to form a relationship with every single grower,” adds Clayton Nevins, new venture lead at Pivot.

“The other piece is just meeting those growers where they’re actually at on their operation. We’ve developed a way to put nitrogen on seed, replacing up to 40 pounds of nitrogen with something that’s just going on top of the seed and into the ground.”

“It’s really hard to drive practice change among growers. And the only way you’re going to do that is by having a solution that meets their needs and serves them well,” he adds. “[Proven 40] just serves growers better, it will generate higher ROI. It works within [a farmer’s] own planting system.”

Nor is farmer trust the sole domain of startups. Frederic Beudot, general manager at Corteva Biologicals, underscores the importance of not just talking to growers but also understanding their specific needs based on their geography and operations.

“As with any new investment, farmers need to be assured their products will deliver high and predictable performance to meet their unique, localized conditions,” he tells AgFunderNews. “They need to know those products will be ready when and where they need them. Biologicals are highly sensitive to soil type, climate and other local conditions, making regionally tailored solutions most effective.”

He says Corteva, which has expanded into the biologicals market significantly over the last few years, has extensive efficacy testing in the lab, greenhouse, and on the farm. “We work closely with farmers to ensure they have the right product, on the right acre, at the right time.”

Marrone says there are still around 50% of growers who are “completely clueless about biologicals” and need more information and education. She said she spends a lot of time reading the labels of biological products and is “amazed” at how nonspecific the information can be.

“Sometimes they’re very detailed and a grower or pest control adviser could follow it; other times, it’s so broad you could use it on anything.”

Companies need to be much more specific about when to use biologicals, and how. “That’s really the key to getting adoption and working with the customers at the grower level demos,” she notes.

“The companies that have succeeded have focused on grower-level pull through. You always, in every case, have to do a lot of grower pull-throughs and demonstrations at the grower level because the distribution channel will not give you the growth that you need. And you have to show that value proposition and have a portfolio of products across the full range of growers needs.”

Biologicals vs. chemicals?

Beudot believes biologicals have a growing place in the market — though he notes that they won’t outright replace chemical solutions.

“We see [biologicals] as a complement to conventional farming practices, giving farmers additional, natural modes of action to protect plants against new and evolving environmental pressures.”

Corteva’s stance echoes that of Bayer, which sees the integration of biologicals as less of an “either/or” situation and more of a “systems approach.”

“Current crop protection products do what they’re supposed to: they protect the production of food,” says Bayer head of strategy fruits & vegetables Peter R. Müller. “Without crop protection today, 40%–50% of yield would basically be destroyed. So we need the effectiveness of chemical products.”

None of the individuals interviewed for this article said they believed biologicals would outright replace chemical inputs, which echoes the over-arching theme of last year’s Salinas Biologicals Summit of an integrated approach where one leverages the other to the benefit of the overall ecosystem.

What startups must do

Startups must consider all of this while operating in a macroeconomic climate that’s currently tough for even large tech companies.

“From a burn perspective, hunker down,” says DuFlock. “You have to try and control your fate. You only control your fate if you control your burn rate, and you only control your burn rate if you’ve got a realistic plan for the headcount; you have the roadmap you need; and the revenue targets you set.”

He says startups are beginning to bifurcate into two groups: those with revenue that can make more of it and those that “just keep talking about making revenue.” No surprises about which group investors view favorably.

“I think about it from the time value of money,” says AgFunder’s Leclerc. “If I have a startup that is compounding with 5% month-over-month growth for 10 years, I’ve got a massive company, right? If I have a company that starts year seven with 10% month-on-month growth, I’m going to be out of that company before it’s interesting; so it’s not going to attract a lot of investment.”

Speeding up time to market is critical for startups nowadays, particularly in biologicals.

Thanks to the speed of technological change, says Marrone, startups can no longer spend seven to 10 years bringing a product to market; they risk bringing an irrelevant offering if they do so. “You have to be much more adaptable to market conditions these days.”

That has to be reconciled against a far more competitive market where a 10%-plus yield increase and 80% win rate on trials is necessary, she adds.

Both she and DuFlock suggest some of this can be sped up by detaching from the “big chem” model that involves 10 to 12 years of development, thousands of field trials, and a 15-year window to, as DufFlock says, “get that chemistry product into the market and make a lot of money.”

“In a lot of ways, I think biologicals have a capital and a time advantage,” he says.

“There’s enough data there because that’s a minimum viable product,” adds Marrone. “A grower wants that product, they have a need for it. And the early adopters will grab it because they don’t want to wait another three years.”

That’s the key for startups right now, she suggests: get the product out there. Yes, companies need good products that are statistically validated. “At the same time, you need to get your product out there and have growers work with you.”

“Some companies do that really well. Others are sitting back in the lab and waiting until everything is perfect. Seven years later, they haven’t launched the product and in that time, 10 others have come to market.”