In the wake of Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods just over a year ago, some of the company’s brightest talent have been entering the agrifood tech investment ecosystem.

Former vice president of grocery Errol Schweizer is now on the board of farm to consumer delivery service Good Eggs, insect farm Aspire Food Group and a large handful of other startups. Former global director of local brands product innovation Elly Truesdell is now chief strategy officer at consumer packaged goods (CPG) investor Canopy Foods.

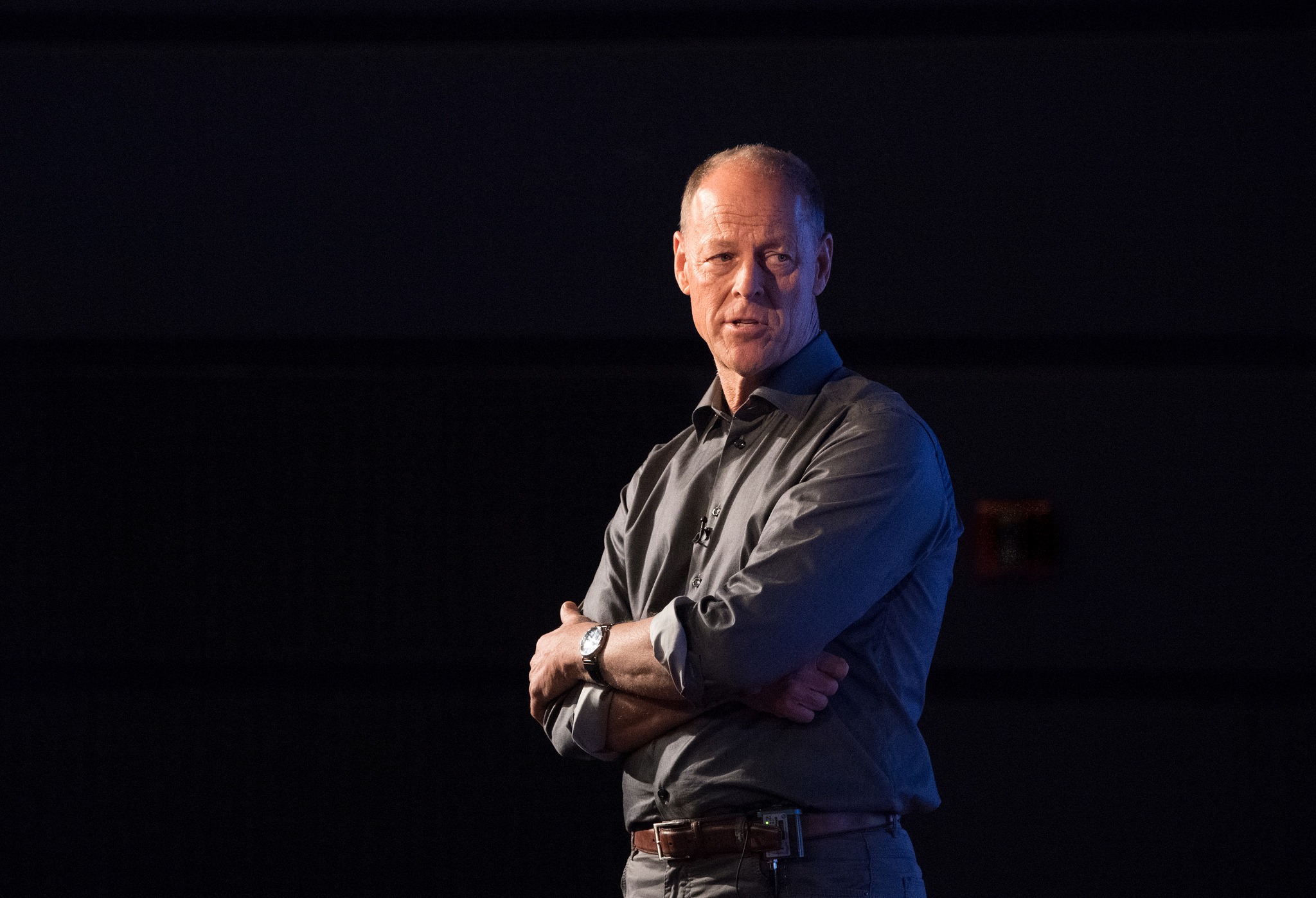

But, the brightest talent of these departures is former Whole Foods co-CEO Walter Robb, who saw the acquisition through and left the company to form Stonewall Robb Advisors in 2017 to advise, invest in and mentor individuals and organizations committed to social justice and animal welfare.

Today, Chicago-based agrifood VC S2G Ventures announced that Robb will serve as executive-in-residence at the firm, helping the team identify new investments and mentor portfolio entrepreneurs who are moving the food system toward sustainability and health.

We caught up with Robb to find out what the view of the food tech gold rush of recent years looked like from the grocery floor and what’s on his mind as he shifts from CEO to advisor and investor.

How did the immense growth in venture capital investment in food manifest at the store level in recent years?

From the beginning of the natural foods industry, it was entrepreneur driven. There wasn’t a lot of mainstream capital around because folks weren’t sure it was going to make it. What I began to see about five years ago was a couple early deals – we had R.W. Knudsen selling to Smuckers and we had Cascadian Farms selling to General Mills. I remember when Bill Knudsen announced that deal. I said “Whoa! We don’t do business with those people! Those people sell the other food.” But they were early harbingers of what was to come.

At the same time, we started to notice at the food shows that there were just as many investment bankers and money folks as any other people there and we really began to see significant money come into the space. People realized that this has generally been an underinvested area, and that has left room for a lot of potential and excitement.

You’re seeing the legacy companies struggle to grow. They’re simply not able to deliver growth. 90 out of the top 100 CPGs have all lost marketshare over the last three or four years because the demand has shifted to a new set of companies, a new set of ideas, and innovation is just happening faster from the ground up and not the top down.

Which foodtech trends did you see really take off in the store at Whole Foods?

Technology is an enabling force and it’s creating a lot more opportunities and capabilities for customers. Think about how customers can get food now. They can get it in so many different ways rather than just coming into the store.

What we saw initially was food grown indoors with vertical farming, we saw new types of alternative meat products, we saw stuff like pea milk – all using new technology. That continues apace right now – Memphis Meats being an example where they are bypassing the cow and just doing the meat.

People still have questions about these things: for example, if I don’t want to eat meat, should I just eat vegetables rather than these various alternatives? It’s still early days for those questions. But what we’ve seen is that the whole world has fundamentally changed because of technology.

It seems like the choices that Whole Foods will have to make regarding what fits its standards and mission and what doesn’t are going to get harder as technology moves forward. How can a natural retailer hold onto its identity and still embrace technology?

Our solution at Whole Foods was we would fully disclose to the customer and let the customer choose. Some things we drew the line on, like cloned salmon. But some of these other technologies we chose to simply disclose. Every company is going to have to make judgments about what they think is appropriate.

I think online platforms allow for much better distribution of information to help customers make those choices. We were about leadership, in terms of our positions on GMO transparency, for example, but we were also about facilitating customer choice.

The GMO transparency piece sounded like a no-brainer in say 2010 and then Impossible Foods comes along and complicates that discussion.

That’s exactly right. This is a whole new generation of foods that didn’t exist and to some extent, we’re gonna have to look at these individual situations and determine if anything crosses the line. On the other hand, Impossible Foods is bringing a non-meat alternative to market and has a lot of money behind it and has created a lot of buzz and publicity. They’ve also gotten it in a lot of restaurants too. I wouldn’t buy the product myself, but a lot of people do.

The meaning of organic and the USDA Organic certification has evolved in the time that you’ve been in the natural foods industry, most recently and controversially allowing for the organic certification of hydroponics. What are your thoughts on the term organic and its usefulness at this point?

It is still very useful because if you look back, it was when that term was codified that the industry really took off because consumers could trust that the industry had some sort of standard. But, I feel like the rule-making process is too slow and if it gets too far behind the customer, I think they are going to realize that the standard isn’t what they thought it was.

I disagree with the hydroponics decision. I feel like they should have done some work on a standard for that category in general before just terming it organic. I think they did it very hastily and I don’t think they thought it out.

I think the organic standard is the best that we have – it’s worth fighting for and preserving. It’s worth making sure that it does mean something because it is a baseline. I am a little disappointed that the Trump administration has gone a few steps backwards with the animal welfare standards so we’re playing a little bit of defense on that right now.

There are a lot of other labels out there that just confuse customers. On animal welfare, there are something like 30 different labels out there. Some of these sustainable labels – what do they actually mean? There’s really nothing that people can sink their teeth into. At least with organic, there’s a basic set of principles that do actually mean something. It’s what we have and we should work to continue to build it.

S2G invests across the agrifood supply chain. What are you most excited about digging into?

I’m interested in advancing the values on which Whole Foods stands, which is the idea of a more sustainable, more just food system. And I believe in thinking about it as a system with all the stakeholders. What I like about S2G is that they have a similar value set and mission. It’s not just investing, it’s trying to use capital to make meaningful change in the food world.

I’m an operator versus an investor per se and I think I can bring a complementary skillset to help the CEOs as they think about growing their companies – both in terms of operating and thinking about their markets, but also in terms of their vales and their culture.

Accessibility, affordability, transparency, and accountability – those are the themes I believe in and I think that technology is part of making that happen.

What’s one thing you’d like to say to venture capitalists about food?

Real value takes time to build and it’s built on enduring values.

photo: USDA