Phytolon—an Israeli startup producing natural food colors via precision fermentation—has secured an undisclosed investment from Rich Products Ventures (RPV), the corporate venture arm of food giant Rich Products Corporation, plus additional funds from existing investors including EIT-Food, Arkin Holdings, and Yossi Ackerman.

Rich’s will also explore using Phytolon’s colors in several of its products from icings and toppings to baked goods in a mutually non-exclusive manner pending regulatory approvals, said Phytolon cofounder and CTO Dr. Tal Zeltzer.

“Rich’s investment and commercial partnership are key to establishing a strong footprint in bakery, desserts, and related segments, where solutions for natural colors are in high demand.”

Cofounder and CEO Dr. Halim Jibran told AgFunderNews: “This investment opportunity naturally emerged from the conversation with Rich’s rather than being a case of our going out and initiating a funding round. Once the communication [with RPV] gathered speed, some of our shareholders then decided to join, which is a great stamp of approval. It all happened somewhat organically.”

“At RPV, we’re investing in venture and growth stage companies that are shaping the future of food through technology and innovation. Sustainable food production is a key area of focus for us, so we’re excited about the cutting-edge work Phytolon is leading and the opportunity that presents Rich’s to create greater value for our customers.” Dinsh Guzdar, managing director, Rich Products Ventures

Performance advantages vs plant-sourced colors

Phytolon’s platform, which is based on licensed technology from the Weizmann Institute of Science, utilizes two strains of baker’s yeast, one modified to secrete a water soluble yellow pigment and the other to secrete a water soluble purple pigment.

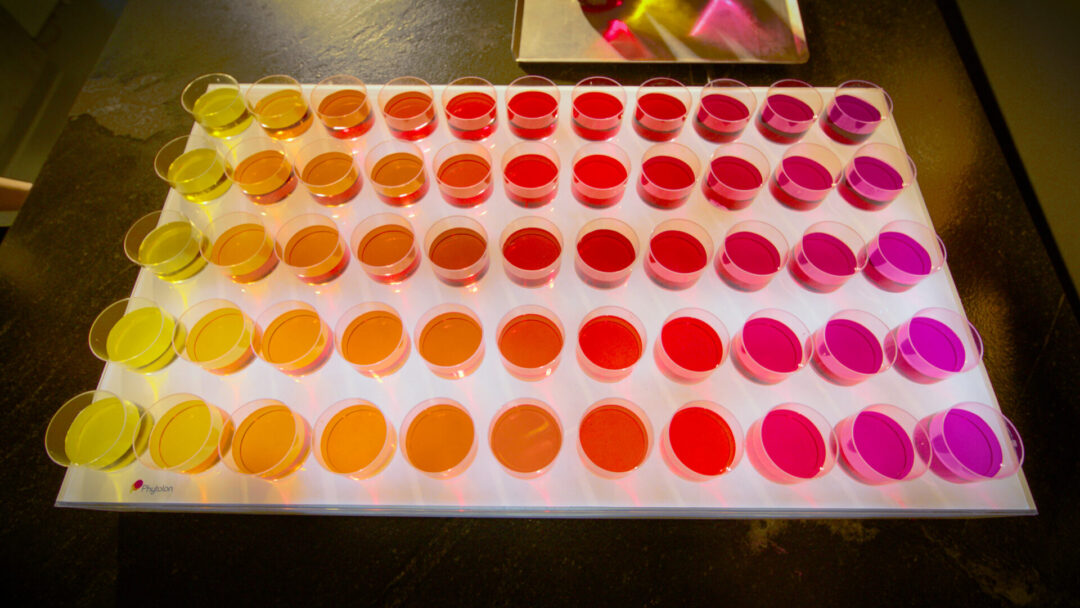

Phytolon can then combine the two to produce a wide range of colors from vibrant reds and pinks to oranges that are stable across a wide pH range, says the firm, which is waiting for the FDA to approve color additive petitions for the two colors.

“We use the same metabolic pathways to make the colors that you can find in beets or prickly pears,” said Jubran, who has been working with Ginkgo Bioworks on optimizing its yeast strains to achieve titers it claims can make it cost competitive with natural colors extracted from plants, but with higher levels of purity, no off tastes, and a more sustainable, reliable supply chain.

“Due to the lack of any plant residuals in the colors, we see an advantage in performance without the off tastes that can come especially when you use [plant-based natural] colors in large amounts,” Jubran told AgFunderNews.

“The purer the color, the less undesired interaction it brings with the food matrix, which also means increased stability of the color. So something like red velvet cake is a very good example of an application where right now, most companies still use synthetics and we think we have the best alternative solution because of our fermentation technology.”

Tech breakthroughs that ‘dramatically reduce the costs of production’

With further optimization, betalain pigments produced by microbes in fermentation tanks could ultimately compete with synthetic dyes, which manufacturers are under increasing pressure to replace, he added.

“We have made some recent progress that dramatically reduces the costs of production.”

While some ingredients utilized by precision fermentation companies are produced within cells (intracellular expression), which have to be broken apart in order to extract the target substance, the yeast strains Phytolon is working with “spontaneously secrete” betalain pigments into the broth.

This means that downstream processing is cheaper because the colors can more easily be separated from the yeast biomass. It also ensures the final products do not contain traces of the genetically engineered host microbe, which can push firms down more challenging regulatory pathways in some geographies, he noted.

Labeling is still to be determined, but as the colors themselves are not GMOs (rather they are produced by GM baker’s yeast, which is filtered out of the final product) they will not trigger bioengineered labeling in the US and will meet criteria for firms looking to make ‘no artificial colors’ claims on pack, said Jubran.

Distribution partnership with DSM Firmenich

Phytolon, which was founded by Jubran and Dr. Tal Zeltzer (CTO) in 2018, recently struck a deal with ingredients giant DSM Firmenich, an investor in the company, to distribute its colors.

But is also establishing direct relationships with CPG companies, as the partnership with Rich’s demonstrates, said Jubran, who said Phytolon has struck a deal with a contract manufacturer to produce its pigments at industrial scale.

“We are in communication with multiple tier one companies, especially in the US, mainly to replace synthetic dyes but also because some of the natural [plant-based] colors that they use are insufficient.”

Asked whether food companies are hesitant about using natural colors produced via fermentation vs colors extracted from plants, Jubran claimed a growing number don’t want vast tracts of agricultural land to be exploited for production of ingredients such as colors or high intensity sweeteners.

They also see the benefits of precision fermentation in terms of securing consistent supplies of product that can be produced closer to end markets, he claimed.

“I think many companies now see that the natural extract solution is not always cost efficient or sustainable in terms of carbon emissions and land and water use. Precision fermentation is a big hope for the food industry to color food in a sustainable and cost-efficient way.” As for the colors Phytolon is expressing in microbes, he said, “They are the same pigments that are produced by plants, just with greater purity.”

Natural food colors via precision fermentation

While genetically engineered microbes are now widely used to create a variety of ingredients from vitamins and enzymes to dairy proteins, precision fermentation tech is still fairly new for producing food colors.

Lycored and others have been using the fungus Blakeslea trispora to make beta-carotene for years, and DDW uses the microalgae Galdieria sulphuraria to produce blue colors. However, these microbes are not genetically engineered.

The best-known player producing colors from GM microbes is Impossible Foods, which deploys GM yeast to make soy leghemoglobin to impart a red color and a ‘meaty’ flavor to alt meat.

Michroma uses CRISPR to optimize filamentous fungi strains that produce stable red colors, although it is not yet on the market, while Debut is working with DIC to develop color ingredients via a novel ‘cell-free’ biomanufacturing platform, which it claims could enable the biosynthesis of colors that are “hard to find or even inaccessible in nature.”